This edition includes all the poems from Ken Smiths two previous retrospectives,

The Poet Reclining: Selected Poems 1962-1980 (Bloodaxe Books, 1982) and

Shed: Poems 1980-2001 (Bloodaxe Books, 2002), the latter including all the poetry which he wished to keep in print from that period. More poems have been included from his first collection,

The Pity (Jonathan Cape, 1967), as well as all the poems from his second book-length collection,

Work, distances / poems (Swallow Press, Chicago, 1972), in their original order but with later revised texts or revised titles taken from

The Poet Reclining in some cases, and with some other poems from the same period added where they appear in the selection he made for

The Poet Reclining. The final section is of poems written after

Shed from the posthumously published

You Again: last poems & other words (Bloodaxe Books, 2004).

Collected Poems does not include the prose of

A Book of Chinese Whispers (Bloodaxe Books, 1987), which remains separately available. More details of original publication are given in the bibliography on page .

CONTENTS

- ROGER GARFITT : Ken Smith: The Poet Reclining

LIFE & WORK, 1: 19381986 - JON GLOVER : Ken Smith: Terra to Shed

LIFE & WORK, 2: 19862003

- * These poems were not included in Work, distances but are from the same period and were printed with them in The Poet Reclining.

- LAST POEMS

ROGER GARFITT

Ken Smith: The Poet Reclining

(LIFE & WORK, 1: 1938-1986) Kenneth John Smith was born on 4 December 1938 in Rudston, a village in the North Riding of Yorkshire, the son of a farm labourer, John Patrick Smith (1904-71) and Millicent (Milly) Emma (

ne Sitch) Smith (1911-90) .

Harsh conditions and an unyielding temper ensured that his father never kept a job for long. The first of the wanderer figures that haunt Smiths poetry were his own family, moving on at the end of harvest: a darker blur on the stubble, a fragment in time gone, we left not a mark, not: a footprint. The isolation of this life meant that he grew up talking to myself and inventing mates, which is where the habit of inventing people and dialogue, stories and fictions began. Solitude intensified when he moved to the city at the age of 13. The horizon shrank, the world became small and hostile. His conversation with himself became silent and turned to writing.

His father had saved enough to buy a grocers shop in Hull, an independence with which he rapidly became embittered. He prospered and bought a second shop, which Smith ran when he left school. But there were continual violent arguments, in which Smith had to defend his mother. It was a situation Smith was locked into until, at the age of 19, conscription released him. In the Air Force he became a typist, and assuaged his boredom by reading widely and completing his university entrance qualifications. He was demobilised in the spring of 1960, returning to Hull, where he married Ann Minnis, a secretary, on 1 August.

In the autumn they moved to Leeds where he read English at the university. Leeds had become an important literary centre. The school of English included Wilson Knight, Douglas Jefferson and Geoffrey Hill, who was then teaching contemporary poetry. Jon Silkin had just completed two years as Gregory Fellow in Poetry and was now an English undergraduate himself. His successors as Gregory Fellow were William Price Turner and Peter Redgrove. Literary activity centred on the weekly magazine Poetry and Audience, of which Smith became assistant editor.

Through Poetry and Audience he met Silkin, and in 1963 he became a co-editor of Stand, an association that lasted until 1969. For a few months after graduating with a B.A. in 1963 he edited, reviewed, and wrote full-time. But his daughter Nicole had been born in 1961 and the pressure of supporting a family soon forced him into teaching, first at a school in Dewsbury (1963-64), then at Dewsbury and Batley Technical and Art College (1964-65). His son Danny was born in 1965 and his daughter Kate in 1966. In 1965 he moved south, to teach complementary studies at Exeter College of Art.

The teaching proved complementary for him too. His own education had been literary and linear: from the art students he learned to think laterally, by image and association, and acquired a much sharper visual sense. It was a development that was to prove crucial to his poetry. His first pamphlet, Eleven Poems, was published by Northern House in 1964 and his first collection, The Pity, by Jonathan Cape in 1967. The Pity was very well reviewed. P.J.

Kavanagh wrote in the Guardian, Anyone who despairs of contemporary verse should be led by the hand to this book. The most arresting poem is the title-poem, which incorporates the lines Mao Tse-tung wrote in prison when his pregnant wife was garroted in the next cell: I cut my hands on the cords at the strangling-post but no blood spilled from my veins; instead of blood I watched and saw the pity run out of me. Writing in Maos voice, Smith gives a restrained and sensitive account of that moment of inner revolution when Compassion takes the hawks wing, diving. In one sense Smiths poetry was released as soon as he was free from study. He wrote The pity and Family group in the week that he graduated. In another sense the poems still felt like studies, the results of conscious writing strategies.

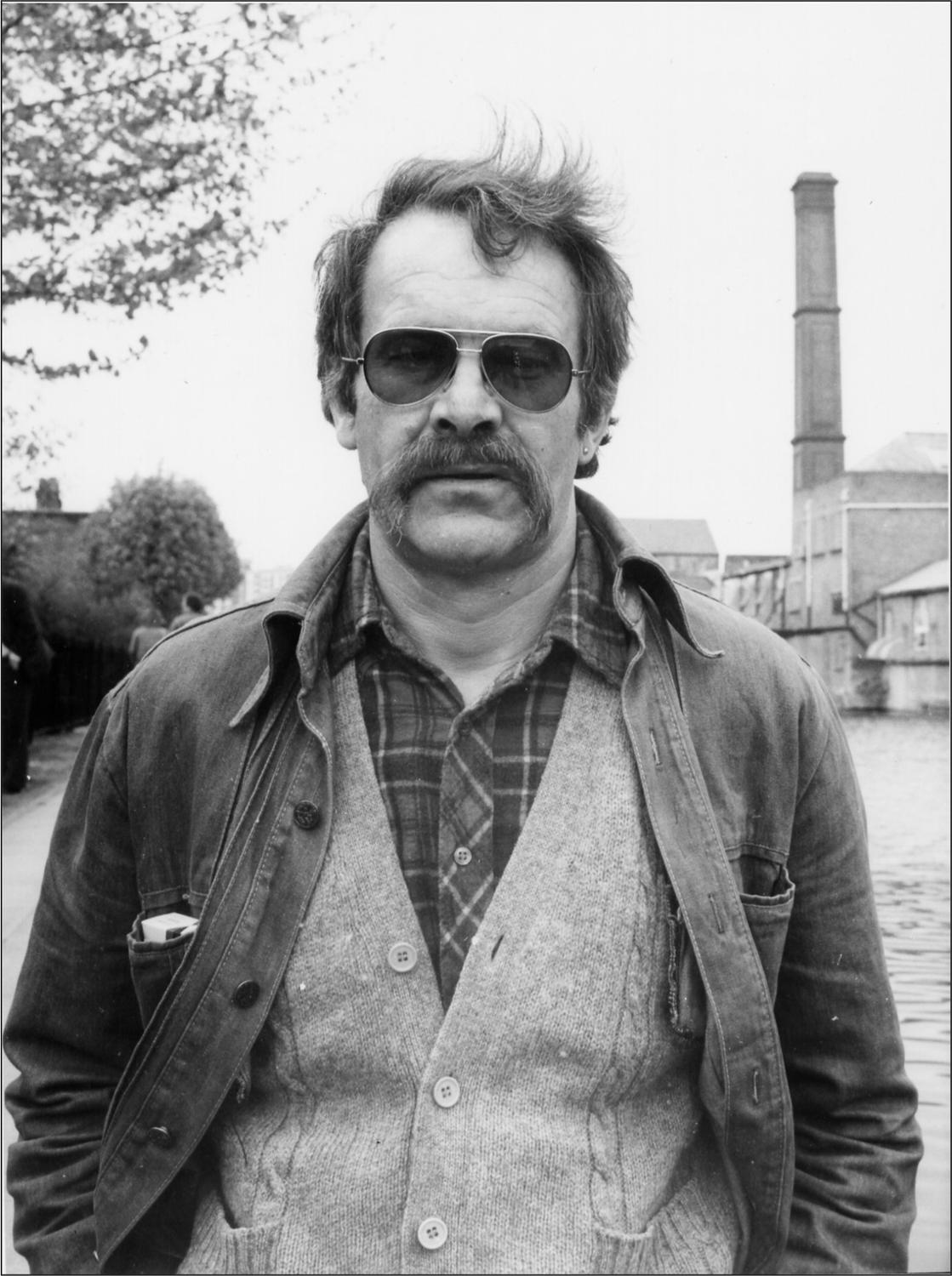

Ken Smith, London, 1982

Ken Smith, London, 1982