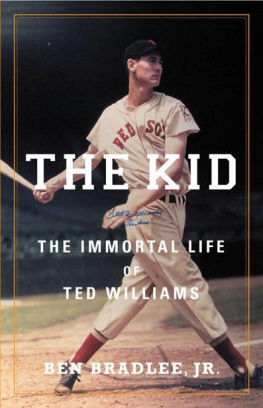

I was in love with Ted Williams.

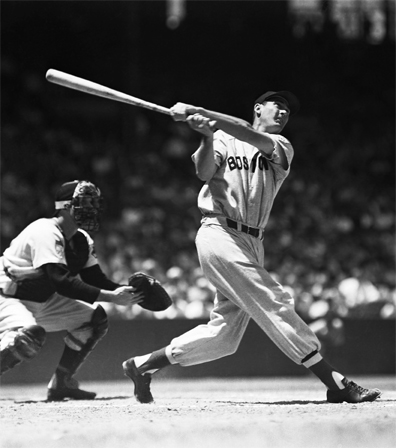

His long legs, that grace,

his narrow baseball bat

level-swung, his knowledge of art,

it has to be perfect, as near

as possible, don't swing

at a pitch seven centimeters

wide of the plate.

I root for the Boston Red Sox

Who are in ninth place

Who haven't won since 1946

It has to be perfect.

BASEBALL, A POEM IN THE MAGIC NUMBER 9

We wish we lived our livesgrace, level-swung, every day a seeking for perfectionas Williams lived his game; if only our lives could be the knowledge of the art of the game. That is worth rooting for, even if we remain in ninth place.

GEORGE BOWERING (1965)

Prologue

T ed Williams loved to tell the story about the alligator. He told it everywhere, told it for much of his life. There were different permutations to fit different circumstances, but the basic story always stayed the same.

Didja hear about the alligator? he would ask.

His voice was loud. His presence was overwhelming.

Bit that kid's leg off!

He would be inside an elevator. He would be inside a restaurant. He would be at some sports fans event, with people waiting in line to secure his autograph on a scrap of paper. He would be somewhere at a ballpark. He would... okay, this was one of the last recorded times he told it... he would be standing in an aisle at Walgreens, holding on to a walker.

Someone else would be with him, someone else to share the joke. Ted Williams would nudge that person, wink, do something to let him know what was taking place.

Terrible thing! Williams would say.

What happened? the co-conspirator would ask if he was sharp.

Terrible thing, Williams would repeat if the co-conspirator was not sharp. Get with the program, buddy.

Here the story would change to fit the circumstance. In Florida, easy, the alligator simply had slipped out of the muck around a local swamp, befuddled by the heat, walked down a city street or suburban subdivision, and found the poor, unwitting kid and started snapping and chewing. In New York, perhaps the keepers were taking the alligator to the Bronx Zoo and he escaped. In Newcastle, New Brunswick, perhaps someone had brought the alligator back from Disney World and slipped it into the Miramichi River. In Boston, Minneapolis, Chicago, right at O'Hare Airport...

Big alligator!

Bit the kid's leg off at the knee!

Kid's in terrible shape!

Don't know what happened to the alligator!

Still on the loose!

Ted Williams would nudge the co-conspirator and advise him to watch and wait. The people who had overheard this dreadful talewho had overheard it from Ted Williams no less, no farther away from me than I am from you; or at least had overheard it from some loud-talking, big son of a bitch at Walgreenswould pass the news. The next people would pass the news and pass and pass. The result would come back like a boomerang. Later in the day. Later in the night. Later in the week. Later.

Did you hear about the alligator? someone would ask the co-conspirator.

Did you hear about the alligator? someone would ask Ted Williams himself.

The following story is not about the alligator. This story is about the man who started all the talking.

Boston

Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox looked as fit as an Indian buck. After a winter out of doors, including a month of lazy fishing at the edge of the Florida Everglades, he was tanned to a light mahogany. His brownish green eyes were clear and sharp, his face lean, the big hands that wrapped around the handle of his 34-oz. Louisville Slugger were calloused and hard. He had 198 pounds, mostly well-trained muscle, tucked away on his six-ft. 334 in. frame. He expected, he conceded, to have a pretty good year.

But as usual Ted Williams had a number of worries at the back of his mind.

TIME, APRIL 10, 1950

T he only other car in the parking lot was a cream-colored Cadillac Coupe DeVille with Minnesota license plates. Jimmy Carroll paid no attention.

The sun was coming up, beautiful, over the Atlantic Ocean. Six o'clock in the morning. Jimmy was supposed to meet some people to go out on some rich guy's yacht from Falmouth, Massachusetts, a town located at the fat beginning end of Cape Cod. One of the people, believe it or not, was supposed to be Ellis Kinder, the pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. Jimmy was a baseball fan. He had driven through the dark from Boston, excited, and arrived way too early.

The door to the cream-colored Cadillac Coupe DeVille opened. Theodore Samuel Williams stepped out.

I didn't know what to do, Jimmy Carroll says, all these years later. He started walking toward my car. I rolled down the window.

Do you know Ellie Kinder? Ted Williams asked. Are you waiting for him?

Yeah, Jimmy blurted.

Well, where the hell is he? Hi. I'm Ted Williams.

No kidding! Jimmy blurted again. Jimmy Carroll.

The sons of bitches are always late. Do you know a place around here where we can get some breakfast?

Well, yeah, Jimmy blurted yet one more time.

Well, come on, let's get some breakfast.

There are other moments in his life Jimmy Carroll can describe with meaning and dramamarriage, divorce, births of childrenbut none are touched with the magic of that 1950s moment. The sun forever sits the same way. The car door always opens. The tall figureJesus, good Christ, it's himunfolds.

Ted Williams becomes Jimmy Carroll's friend.

We'd take rides, Jimmy says about the relationship that developed long ago. He loved to take rides. He loved going along the Charles River. We'd make the whole loop, over to Cambridge, out to Newton and back. He'd be talking about all the places we passed, asking questions, making comments. We'd take walks. We'd go down Marlborough Street at night, really quiet and dark, a lot of college kids living there, come back up Beacon Street. Noisier. Cars would stop. People would shout.

I took him all over the place. I took him out to Nantasket once, to the amusement park. Mobbed. We could only stay about five minutes. I took him to South Boston. Mobbed. He signed autographs for all these kids at the L Street Bath House. I took him... one day we're sitting around, doing nothing, and he says, Let's go somewhere. Where can we go?' I said, Why don't we go over and visit James Michael Curley, the former mayor of Boston? He's very sick.' Ted said, The guy who went to jail because he was taking money to help the little guy?' I said, That's the one. He threw out the first pitch on Opening Day a couple times. You know him.'

We go. Ted Williams to see James Michael Curley! We get shown into a bedroom. There's two twin beds. Curley is in one of them. You can see he's close to dying. He's delighted to see Ted, though. He's a fan. Ted gets in the other twin bed! Curls up! They lie there, the two of them. Talked for an hour!