The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

If the world is torn to pieces, I want to see what story I can find in fragmentation. I have taken to making collages. I want to see whether a different narrative might arise from poring over American magazines, tearing them up, and putting them back together in a shape that makes sense to me. When everything feels like it is coming apart, the art of assemblage feels like a worthy pastime. It is said that when John Ashbery lived in Paris, from 1958 until 1965, he took to making collages because he felt so isolated from America and its language. He said, You can make a collage on a postcard and write a poem about it.

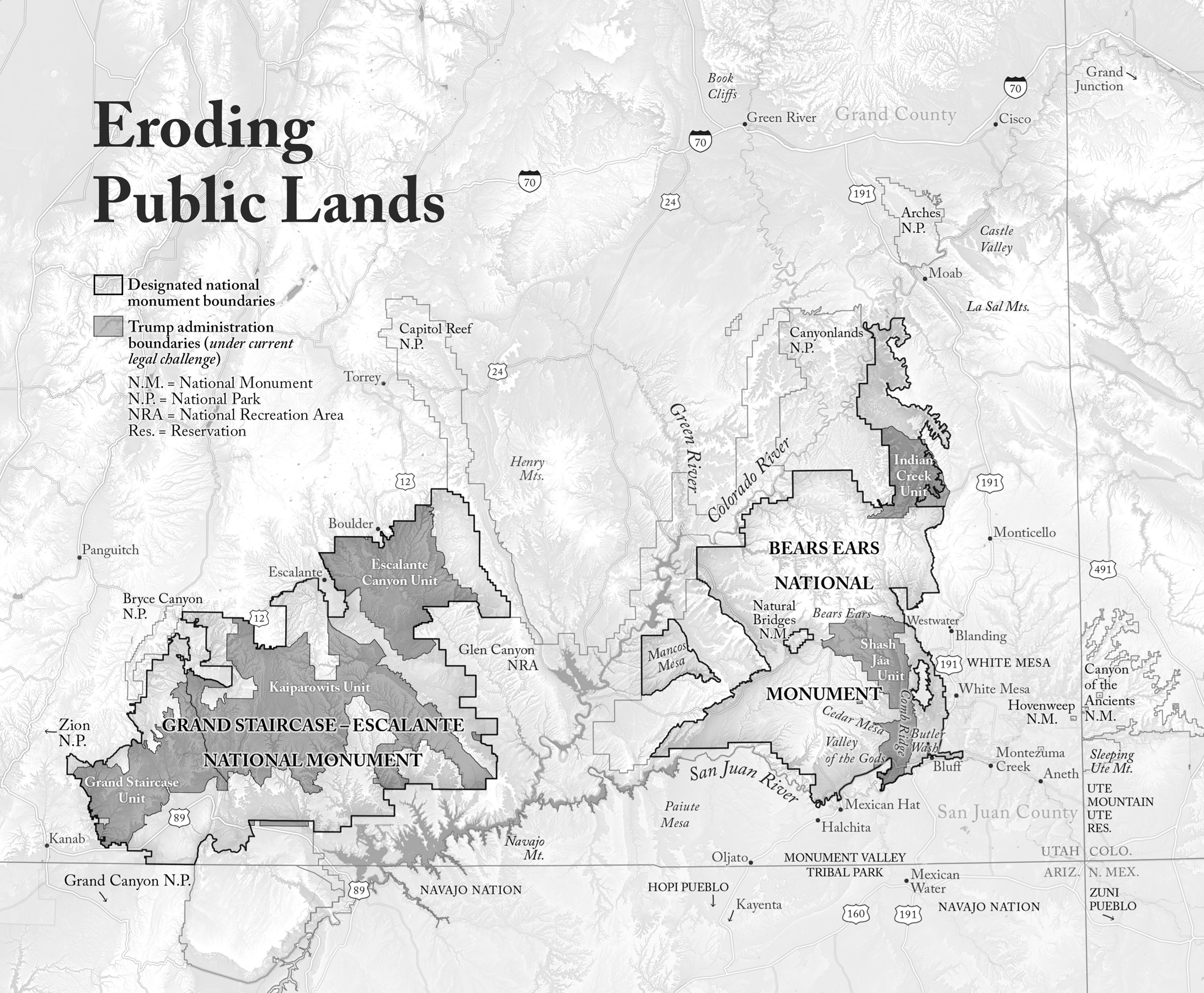

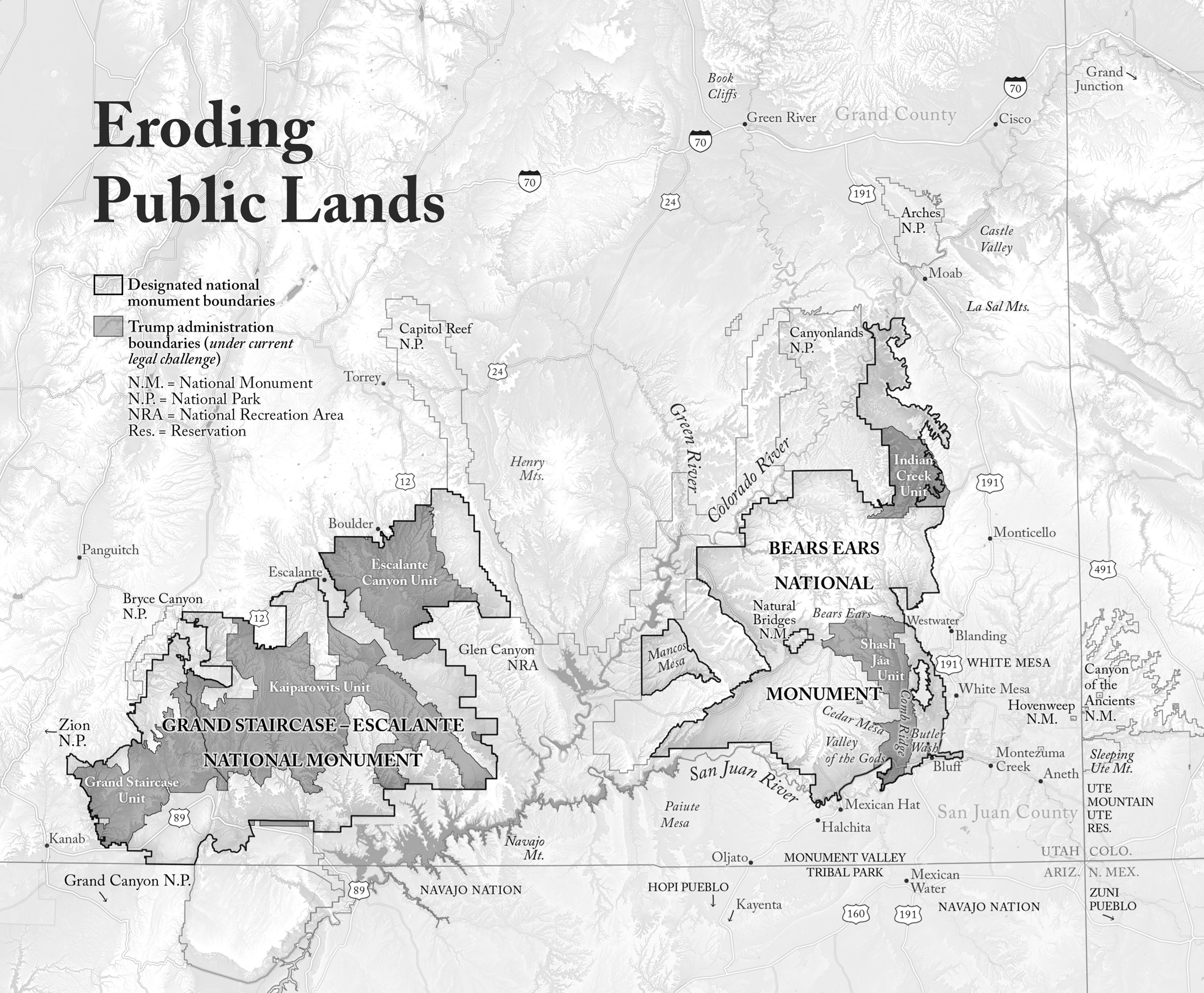

Perhaps these essays are my postcards from home, a cutting and rearrangement of the collusions and chance associations I am witnessing in the American West. This is a moment of strange juxtapositions. On one day, I am undone by the absolute stillness of where we live in Castle Valley, Utah. On another day, we awake to what sounds like war games: helicopters buzzing Adobe Mesa, with filmmakers hanging halfway out the aircraft as they attempt to document a superathlete traversing the worlds longest slackline, stretched across a sandstone formation called The Priest and Nuns to Castleton Tower. What is home to some is a playground for others. Every day brings a different surprise. A new road is being cut into a canyon for natural gas extraction. Another town meeting takes up a proposed coal plant or the return of uranium mining on the rim of the Grand Canyon.

We can take nothing for granted.

I am aware of my restlessness. I am waitingwaiting for what? Scenes from Samuel Becketts play Waiting for Godot keep returning to me: Was I sleeping while others suffered? Am I sleeping now? Tomorrow when I wake, or think I do, what shall I say of today? That at this place, until the fall of night, I waited for Godot?

After a season at home, I left Castle Valley for work in Santa Fe. I had heard of a family of artists named Namingha, of Tewa-Hopi descent, Dan Namingha and his two sons, Arlo and Michael. I went to their gallery before I had to teach. I walked in, and before my eyes could adjust to the light pouring in from outside I saw an aerial photograph on the wall: the Colorado River meandering through the sage desert with a large turquoise triangle made out of plexiglass cutting into the landscape. It was an installation called The Escalade Project, by Michael Namingha. Tears started streaming down my cheeks. I couldnt say why. All I knew was that I was feeling something again. My heartbreak was being met. I sat down on the floor, took out my notebook, and started writing. Words flowed onto the pages like water.

Michael Namingha introduced himself. He saw I had been moved. We stood in front of his installation and talked about what moved him to create it: a tramway perched on the edge of the Grand Canyon, designed to take tourists down to the confluence of the Little Colorado River, a sacred site of origin for the Hopi. He spoke of how the Turquoise Triangle represented, for him, both the land itself and the spiritual essence of the land being lost as it was being cut out, removed, destroyed, disappeared. What I hadnt been able to articulate verbally for months, Michael had articulated for me visually. The emotional dam I had constructed for myself since the 2016 election, broke. I watched the words buried deep in that reservoir of grief surface.

This is a collection of essays written from 2012 to 2019, a seven-year cycle exploring the idea of erosion: the erosion of land; the erosion of home; the erosion of self; the erosion of the body and the body politic. It is a book of competing dreams and actionsthe arc between protecting lands and exploiting them and, for many, not seeing them at all; between engaging politics and bypassing them; and the spectrum between succumbing to fear and choosing courage.

This is a gathering of stories, poems, and pleas in the name of Beauty in an erosional landscape sculpted by wind, water, and time. It is also a book of questions. Whom do we serve? How do we survive our grief in the midst of so many losses in the living world, from white bark pines to grizzly bears to the decline of willow flycatchers along the Colorado River? How do we hold ourselves to account over our inescapable complicity in a fossil fuel economy that is contributing to climate change, as well as ravaging tribal and public lands in the American West? What are the necessary actions we can take in order to realize justice for all? And how do we find the strength to not look away from all that is breaking our hearts?

The paradox found in the peace and restlessness of these desert lands, where rockslides, flash floods, and drought are commonplace, allows us to embrace the hardscrabble truths of change. In the process of being broken open, worn down, and reshaped, an uncommon tranquility can follow. Our undoing is also our becoming.

I have come to believe this is a good thing.

TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS

Vernal equinox 2019

An equality of survival does not exist We have both the responsibilityand the abilityto protect one another.

ELAINE SCARRY, Thinking in an Emergency

Not long ago, a friend visited us from New York City, planning to stay several days in the desert. But after her first night, we awoke in the morning and found her with her bags packed, standing at the front door. She had changed her plane ticket for an early return to Manhattan. Her last words to us as she left were Arent you afraid you will be forgotten?

What I wanted to say but didnt was I hope so.

None of us see landscape the same.

Each of us finds our identity within the communities we call home. My delight in being forgotten is rooted in the belief that I dont matter in the larger scheme of things, only that I tried my best to be a good human, failing repeatedly, but trying again with the soul-settling knowledge that my body will return to the desert.

Robin Wall Kimmerer tells the story of a beloved professor who had the initials NYS written behind his name. It stood for not yet soil. Amen.

For those of us who live in arid country, red dust devils as commonplace as sage sandblast any notion of self-importance right out of us.

Yet still, we forget.

I write to remember.

It is dark, the sun has yet to rise, and a candle is lit on my desk. It is the last day of the year, a difficult year, and I am up early, unable to sleep. People often ask how we can stay buoyant in the face of loss, and I dont know what to say except the world is so beautiful even as it burns, even as those we love leave us, even as we witness the ravaging of land and species, especially as we witness the brutal injustices and deep divisions in this countryas exemplified by the separation of families seeking asylum at the southern border; the blatant racism exposed in Charlottesville; or the students encounter with a Native elder drumming at the Indigenous March in Washington, D.C. The erosion of democracy and decency feels like a widening crack on the face of Liberty.