Contents

Landmarks

Page List

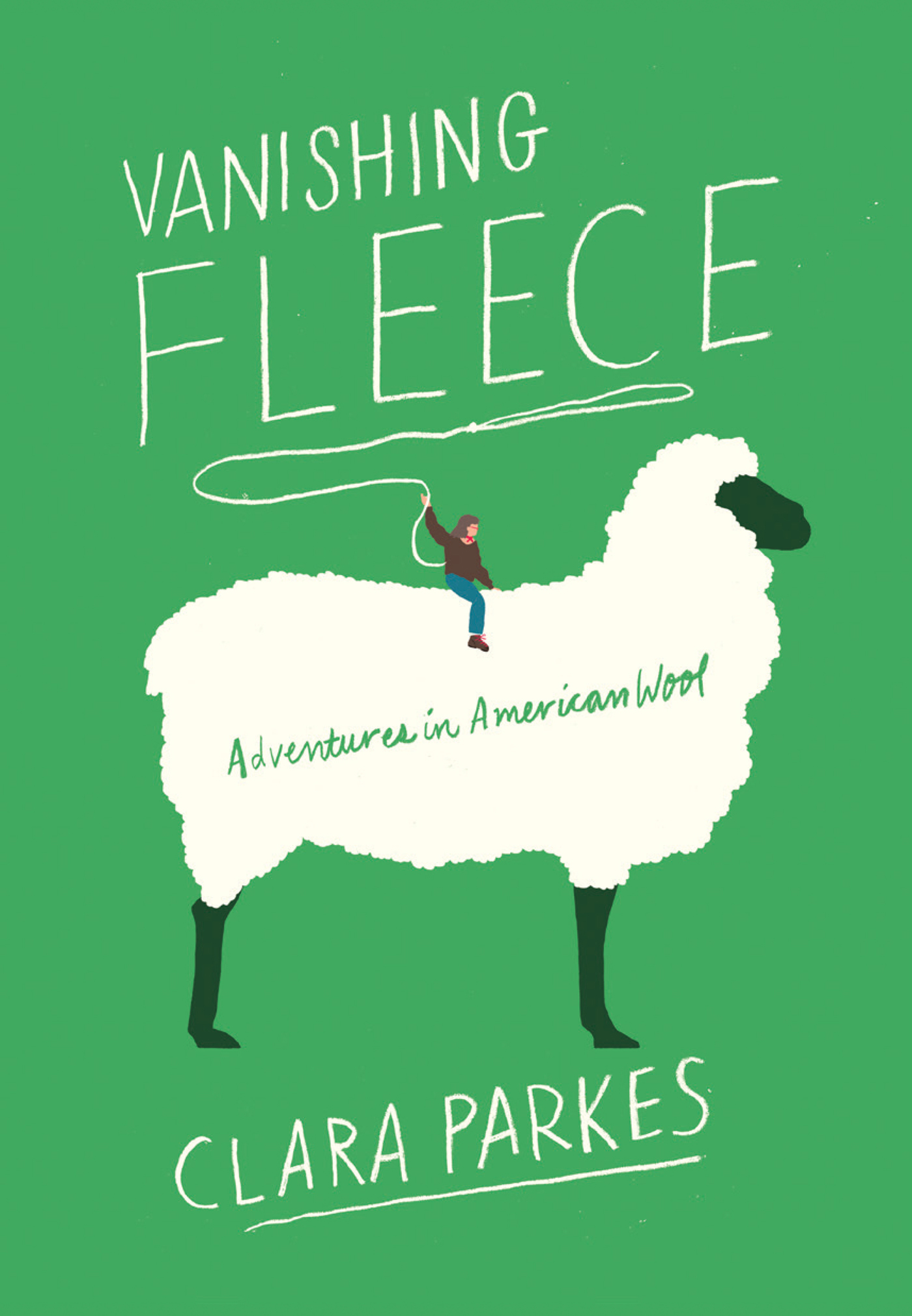

Copyright 2019 Clara Parkes

Cover 2019 Abrams

Published in 2019 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958831

ISBN: 9781-419735318

eISBN: 9781-683356820

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

for Eugene

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

GIRL MEETS BALE

Rhinebeck, New York. A series of debacles had left me at a daylong signing at one of the countrys biggest sheep and wool festivals, all doped-up on migraine meds and with my underwear on backward. Lets just say I was not at my best. Late in the afternoon, I noticed a tall, distinguished-looking man standing a few paces away from my table. I assumed he was waiting for one of the people in line, but when the line disappeared he still stood there, studying me with an inscrutable smile. Finally he approached and held out his hand. My name is Eugene Wyatt, he said. I raise the largest flock of purebred Saxon Merino sheep in the United States.

My heart skipped a beat. Id made a life out of traveling the world in search of noteworthy farms, flocks, and people to write about. Here Id hit the jackpot. Eugene had eyes the color of a Swiss lake, crisp and piercing. He wore a barn jacket that had clearly seen the inside of a barn, with scratches and stains that added to his rugged mystique. He couldve easily been Robert Redfords older brother. He had that presence about him.

We immediately got to talking. Talk turned to correspondence, which turned to a friendship of mutual respect that endured for years. When I began investigating making a line of yarn for a national company, Eugene was the first person I asked for fiber. He asked smart, tough questions that made it clear the business move wasnt in my best interest. I canceled the yarn line, but I kept Eugenes wool in the back of my mind. Surely there had to be a way we could work together?

About a year later, the email came. He filled me in on how shearing and lambing had gone and how his wool had performed at the lab. Every year he sent samples to the Yocom-McColl Wool Testing Lab in Denver for analysis. Its the last independent commercial lab of its kind in the United States, still operated by its founder and now-octogenarian Angus McColl. Using high-tech equipment, Anguss team measures things like average fiber length, strength, curvature, cleanliness, and diameter. That last one is measured in microns, or millionths of a meter. Most fine Merino wool falls between 18.6 and 19.5 microns, while human hair averages 75 microns and cashmere ranges from 14 to 19 microns. That year, Eugenes clip was trending between 17.4 and 18.7 micronson the finest end of Merino and squarely in the range of cashmere. He was pleased.

Id gotten similar emails from him before, but this time, he added a curious paragraph at the end:

Also, I wonder where you are concerning the yarn project we spoke about a year or so ago. The reason Im asking is that I have a 676-pound bale of scoured Saxon Merino wool. Right now its more than I need...

Eugene always chose his words very carefully. He didnt leave an ellipsis because hed forgotten what else he wanted to say. Hed left me an invitation. Could I think of any fitting use for that bale? Such an amount of wool, 676 pounds, is tricky. Its not enough to start a yarn company or even, for that matter, a yarn line. But its way more than any reasonable human being needs for her own personal pleasure. (Ill let you debate what constitutes reasonable.)

Still, the question remained: What could I do with it?

A crazy idea began to form in my head. An epic, exciting, terrifying idea. Before I could stop it, all the details were there. I knew exactly what I could do with that bale.

The entire project landed in my lap like a fully decorated cake tossed from a moving car. I grabbed it instinctively before my brain had a chance to talk me out of it. But instead of a cake, it was a 676-pound bale of wool. I spent the next ten months trying to persuade myself it was a bad idea, trying to avoid thinking about it, trying to pretend I had a choice in the matter. But in my heart of hearts Id already committed. My fate was sealed; the bale was a done deal.

As crude oil ships by the barrel and apples by the peck, wool moves about in bales. Measuring the approximate size of a claw-foot bathtub and weighing two-thirds the weight of a grand piano, a bale contains billions of tightly compressed wool fibers held in place with taut steel wires and wrapped with a thick coat of plastic. You cant move one without the aid of a pallet jack, a forklift, or at least three professional weight lifters. A bale is a presence and a commitment.

Most normal people would, upon being offered a chance to purchase an entire bale of wool, likely respond with a polite, if not somewhat confused, No thank you. Unless you operate your own ready-to-wear clothing line, you probably dont need enough wool to make 170 blankets, or 650 sweaters, or 1,500 pairs of socks. Especially if the wool hasnt even been spun into yarn yet.

But this was no ordinary bale. Eugene had spent more than thirty years tirelessly breeding and culling his flock to refine the bloodline of this rare, prized strain of Merino sheep whose wool is as fine as cashmere. That single bale represented a years worth of work for my farmer friend. He could have easily sold it for twice what he was quoting me. Or he couldve used it to make more of his own yarn that he sold at New Yorks Union Square Greenmarket every Saturday. But for reasons unknown to me at the time, Eugene wanted mea person who only writes about yarn and has no manufacturing experience whatsoeverto have it.

Since 2000, Id had a successful career as the worlds first and probably only professional yarn critic. I got to teach and write articles, to be on the radio and TV, and to write books. By the time Eugenes bale came into my life, Id been doing the same thing, chewing the same cud, for thirteen years. Maybe Eugene saw it first, but I soon realized it myself: My interest was starting to wane. Everything began to look the same; every story seemed to be repetitive. I was having a harder and harder time summoning enthusiasm for my subject. I felt like I was on the verge of coasting, just slicing and dicing the same bit of knowledge in as many permutations as possible to make it interesting to me again, as well as to my readers. Turn passion into a profession and the spark inevitably fades, I figured. I plodded on.

It didnt help that nine-tenths of the world already thought my job was a joke. Knitting is laden with so many cultural stereotypes that the notion of someone making a full-time career out of reviewing yarn made most people laugh and say, No, seriously, what do you do? When Id say Id been doing it for more than a decade, they usually backed away.