LANDSKIPPING

LANDSKIPPING

Painters, Ploughmen and Places

Anna Pavord

Dedicated to the inheritors: Josh, Romilly, Raf, Zac and Ziggy Dale, Maisie, Tom and Agnes Ringer, Jack, Fergus, Xan and Hector Gathorne-Hardy

CONTENTS

| The Sugar Loaf A Picnic with Pythagoras Celts against Romans Which Landscapes? Wasdale The Fell Hounds |

| The First Tourists Looking by the Book Thomas Gray and his Traitorous Claude Glass In Search of Wordsworth Suspended Between Two Firmaments |

| Gainsborough Shuts up his Landscapes The Eidophusikon Paul Sandbys Journey to the Fag End of Creation The Last Bard Burke and the Sublime William Gilpin is Correctly Picturesque The Rules of Beauty Tintern The Wrong Kind of Ruin |

| Unconscious Imprints The North Norfolk Coast The Magnificence of Northumberland To Agitius, Three Times Consul The Groans of the Britons A Sublime Shift |

| Consequences of the War with France John Constable and the Banks of the Stour A Landscape Abounding in Human Associations The Chiaroscuro of Nature Spring. East Bergholt Common, Hail Squalls. Noon Constable Lectures to the Literary and Scientific Society of Hampstead Richard Wilson The Neglect of a Tasteless Public Llyn Cau |

| Wester Ross Loch Carron How Rain Remakes a Landscape Waterfall Songs White Noise Black Peaks Falls of the Clyde Turners Liber Studiorum The Ghosts that Live in a Landscape The Delight of Melancholy The Sound of Raasay |

| To the Sea Dark Waters at the Goultrop Roads Slowing Down Speed A Landscape of Ritual Hugeous Stones Cornelius Varley Watches Clouds |

| Thomas Johness Dream A Frenzy of Larch The Correctly Educated Traveller A Derby Dessert Service Spending Three Fortunes From Bog to Pasture Intractable Tenants Model Cheeses An Earthly Eden |

| A Different Way of Looking Process Not Product William Marshalls Rural Economies Arthur Young on the Hoof The General Views Cultivated Land and a Civilised Society Ploughs Too Bad for Description The Improvers George Kay Has a Hard Time A Patriotic Duty The Landscape of Lancashires Mills Marshalls All-Seeing Eye |

| The First Rural Ride A Splenetic Guide The Creep of the Wen Nice Sweet Fuel A Man Who Speaks and Thinks Plain The Speenhamland System Radical Swedes The Superiority of Woodland Counties The Supremacy of Ash Happy Hampshire |

| Birds in Flight A Clamour of Rooks Animating the Landscape Roosts Sheep Shape Sheep Leazes and Water Meadows The Importance of Folding Hurdles and Hazel Robert Bakewells Two Pounder A Testing Time for Rams |

| Estover, Turbary and Pannage The Commons Preservation Society Searching for a Model Management Scheme Biodiversity or Access; What Do We Want? The Difficulty of Understanding the Plot |

| Maps Local Distinctiveness A Landscape of Bureaucracy Domesday Surveying the Country Pigs or Poppies Shaping the Land Hedges Old and New The Bully Boys A Sanitised Masquerade |

| Naming Places Geological Imperatives Hoskinss Golden Age Enclosures Disbeautifying an Enchanting Piece of Scenery Our Richest Historical Record |

| Celtic Hill Forts Singularities of Landscape Jewels to Gather An Inexorable Timetable Protecting the Landscape? Putting Golf First Evensong John Gales Virginals The Powerstock Tithe Map Puzzicks and Flinty Nap Absalom Guppy and the Workhouse |

| Architecture as a Window on the Soul Stinsford or Westminster Abbey: Where Do You Leave the Flowers? Water Meadows, the Silver Gridirons Egdon Heath The Archetypal Wood Natures Indifference A Blizzard from a Bright Blue Sky |

| A Prospect An Occupation Predisposition Contemplating a Quiet View Marks Made and Rubbed Out Time Measured by Different Clocks Michaelmas Ancient Bones A Morning in May Lighting Up the Landscape A Pedigree Bull Hefted to the Hills |

| A Funeral at Llanddewi Rhydderch The Glittering Valley |

LANDSKIPPING

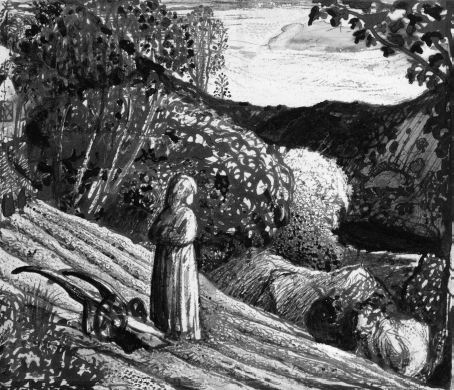

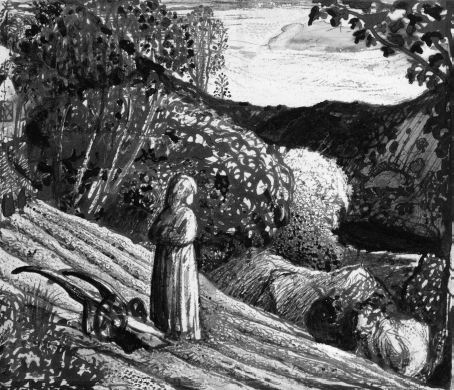

Samuel Palmer, Landscape, Girl Standing (c. 1826)

You wouldnt exactly call it a mountain. More of a hill. But where I grew up, in the border country between England and Wales, it was the tallest thing around, 1,200 ft and pointed, a distinctive triangle rising up on the backs of the Deri, the Rholben and the Llanwenarth Breast. To me, the Sugar Loaf was certainly a mountain. In fact, I thought it was a volcano, although my father in his clear, schoolmasterly way, explained several times why it could not be. It was very smooth, silhouetted against the sky. The scrub oaks that grew over the softer slopes of the three lower hills stopped as they came within sight of the Sugar Loaf. Too steep. For me as well as them.

But we often climbed it. Round the side of the Sugar Loaf, where the landscape opened out on to Forest Coalpit and the Black Mountains, there was a boggy place where globeflowers grew. There were kingcups everywhere along the streams of my uncles farms, but the globeflower paler, taller, more poised was a rarity and we went every year to admire them, a kind of pilgrimage for my mother. She was a great botanist in the old-fashioned way. She could name every different kind of grass in any field she walked through. She made a collection of them, pressed pale and bleached in a book of cartridge paper, with their names, common and botanical, written in white ink underneath.

She could name the owner, too, of almost every farm we looked out on to from the high sides of the Sugar Loaf. Shed been born in this landscape. So had my father. It was intimately known. We climbed up on to the flanks of the Sugar Loaf to gather winberries, always in the same china cups, too cracked to hold tea, but too pretty to throw away. The day before my geometry O level, my mother was waiting after school with a picnic in a basket and we climbed up through the beech trees of St Marys Vale to a spring on the side of the Sugar Loaf where she tested me on my theorems. Pythagoras would stick better, she firmly believed, if it was taken in with a view.

So the square on the hypotenuse is inextricably mixed still with bracken, tall and green, the slightly damp acid smell of the turf always cropped short by the sheep on the hill and the view back down over the Deri and the Rholben to the Usk shining in the valley below. Beyond the river was the Blorenge, where we never went.

Partly this was a matter of geography. We lived just underneath the Deri, so naturally it was the landscape we were most often in, the one we knew best. We would have needed transport, which we did not have, to get over the river to the Blorenge. And it was a big, bare, forbidding hunk, with a dip in the flank that faced our house, where shadows gathered too early. There was another reason to stick to our side of the river. The Blorenge was a kind of gatekeeper to another country. Lying in bed at night, I could see from my window the great flares that lit up the sky from the furnaces of the iron masters, Guest, Keen and Nettlefold in Brynmawr and Blaenavon. Over there, the valleys which had once been green were bounded by grey-black heaps of slag. So, I suppose the fragility of a landscape was stitched into me from the beginning. And a need for land to go up and down if Im to feel comfortable in it.