THE BIG SNOW

NOVEMBER (1980s)

It was mid-November and a winter storm was coming to the mountains of northwest Wyoming. The wind was gentle, chinooklike, swaying the bare branches of an aspen grove against a gray sky. The trees leaves, already drawn to the forest floor by the October frosts of the brief Rocky Mountain autumn, lay silent under crusted drifts of November snow. I struggled carrying a bulky rucksack up the open slope toward groves of mixed fir, spruce, and pine. I had a 9,000-foot ridge to climb, another valley to drop into and cross, then a steep north-facing mountainside to crawl up until I reached the 9,200-foot contour.

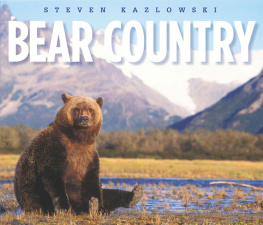

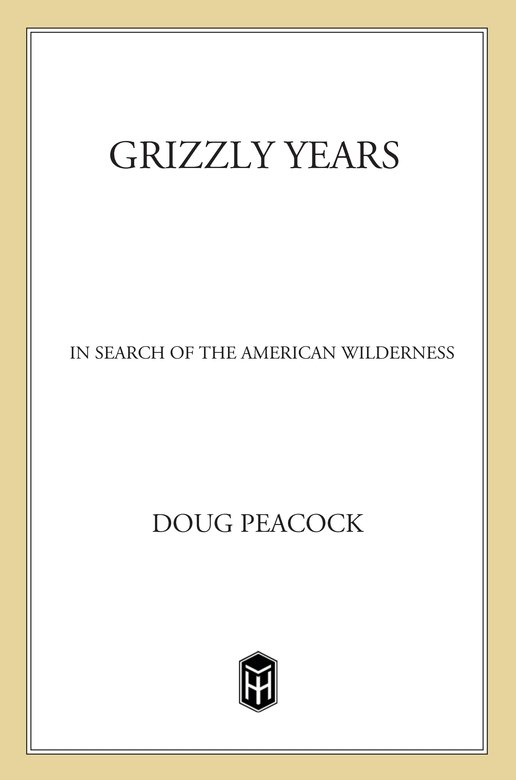

At that elevation, under the roots of a large, lightning-struck whitebark pine, was a five-foot-long tunnel dug into the side of the forty-degree mountain slope. The hole had been dug by a young grizzly bear. I knew because I had watched him dig it. He had started on the twentieth of September, removing hundreds of pounds of gravelly loam. He planned on sleeping out the winter in there. When he wasnt working on his den, he fed on the whitebark pine nut caches of red squirrels. In October he left the area. If he had not yet returned, this storm would, I thought, bring him back.

The upland country of the Yellowstone Plateau was open, pleasant country. I stepped across a tiny creek and saw, hiddenbehind a boulder, a layer of golden aspen leaves placered against the bottom of a dark pool. The tops of yellow grasses were still exposed in the meadows; under the shadows of the conifers, low banks of windblown snow awaited winter. The breeze drifted north of me on the lee side of the ridge, while a high wind ran over the rocky spine above.

Through my binoculars, far below me, a bull moose stood motionless in the bushy willow bottomland. The elk and a small herd of mountain sheep on the distant slope had bedded. My blood felt sluggish too. The barometric lows preceding major storms heralded lethargic times: the ungulates brushed up, the fish did not bite, and the grizzlies hightailed it to denning sites, where they moped around and waited for the big snow. Grizzlies could sense winter storms days in advance. My three-year-old bear was probably putting the finishing touches on his den just then, raking it out one last time before adding beddinggrass, moss, or boughs of young firs. He would then withdraw to his porch, a dish-shaped depression in the loam just in front of the three-foot-wide opening to the tunnel, and lie like a sleepy puppy watching the darkening skies for the whiteness that would seal him within his mountain.

I walked uphill under the canopy of mature whitebark pines. Under a large tree, next to the trunk where the snow had melted, was a small pile of pinecones. A bear, probably a grizzly, had dug up a number of squirrel caches and raked out the seeds with his claws. Red squirrels were the middlemen; bears did not harvest the cones directly but were dependent on the arboreal rodents. Even in years when there were lots of pine nuts, if the squirrel population was down, the bears would not get many nuts. These pine nuts were a major source of food for Yellowstones grizzlies. The three-year-old grizzly had been feeding on mast when I had stumbled across him digging his den six weeks earlier.

I climbed over a string of mossy ledges and topped out the ridge. Before me, to the south, lay the gentle, rolling up-country of the Snowy Range: willow bottoms, sagebrush meadows, and undulating grassy hillsides patched with groves of aspen and stands of pine and fir. The den site of the three-year-old bear lay four miles away, up on the steep side of the next low mountain. I could have gotten there by dark if I had pushed. But I had not comeout here to hurry. Instead, I would hole up for the night and wait for the snow to begin falling.

Grizzlies at their denning sites are extremely shy; if they are disturbed they may abandon the area altogether and be forced to dig another den somewhere else. Once the first major storm of the fall begins, undisturbed bears become sluggish and are much less likely to be bothered by my presence. But I didnt plan on letting this little grizzly know I was around.

The high wind had died. The air felt heavy, still warm under its blanket of monotonous blue-gray sky. The snowy front pushed before it a low-pressure trough of languid creatures, a chorus of yawns. I stumbled down the mountain slope, through the dead grasses and winter trees, toward a narrow creek that meandered through willow thickets. By the time I reached the valley, just at dark, the wind had stopped altogether. The air was still and snow had begun to fall. Nothing moved except the large white flakes and the small creek, whose dark currents gathered the silent snow.

I followed the tiny creek up into the trees where the waters pooled behind the roots of a giant spruce. An eerie calm settled in over the mountains as I located a spot to sit against the huge spruce. I gathered wood from a nearby whitebark and kindled it with dry twigs off the lee side of a smaller spruce. I dug a down parka and wool stocking cap out of my backpack and prepared for a long night of staring into the fire. The temperature was dropping. The snow would be dry, and the spruce boughs would keep most of it off me. I carried no tent or sleeping bag this trip. I planned on sitting up all night tending the fire.

I spread out a small groundclothraingear, actuallydug into the bottom of the pack, and pulled out a foot-long oblong bundle wrapped in a spare wool sweater. I unwrapped a skull and placed it next to me facing the fire, balancing the upper jaw carefully upon the mandible. It was the skull of an adult grizzly, a female. I had come by it in the White Swan Saloon in the town north of here. A local horn hunter, a friend of mine, had bought it for me from a rancher who had poached the bear three months earlier on a grazing allotment in the national forest a few miles from the border of Yellowstone National Park. The same sheepherder had also shot at, but missed, another grizzly who washanging around the female. That much was common knowledge. What was not known was that the two bears were related, and the previous winter they had denned together up the hill a mile south of my fire.

I didnt know what to do with the skull at first. I just did not want the sheepherder to have it. He had already made enough money selling the bears paws and gallbladder. The sow grizzly had never killed any sheep that I knew about, though that didnt mean she would not have started at any time. At the time she was killed, the female grizzly was almost eight, fairly old by Yellowstone standards. She had successfully mated once, probably when she was four and a half. The following winter she had given birth to a single cubat least there had been only one cub with her the next spring, when I had gotten to know her. She had emerged from the den in late April, dropped down to the valley I had crossed an hour earlier, and fed on an elk carcass. I had backtracked her to her winter denning site. She and her cub had made a highly distinctive family: the sows fur had a slight golden hue with a darker stripe running down her back. The cub had been nearly black with a silver collar extending into a light-colored chest yoke, which had faded sometime during his second year. They had been back on these slopes feeding on pine nuts the same fall, and I found their den the following spring. Altogether I had found five dens on this same hillside within a few hundred yards of one another. All but the first could have been dug by the same female.