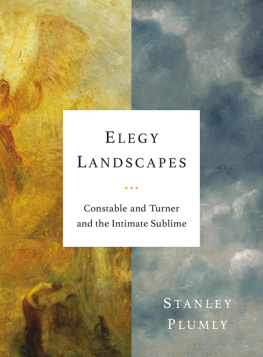

ALSO BY STANLEY PLUMLY POETRY Old Heart Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me:

ALSO BY STANLEY PLUMLY POETRY Old Heart Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me:

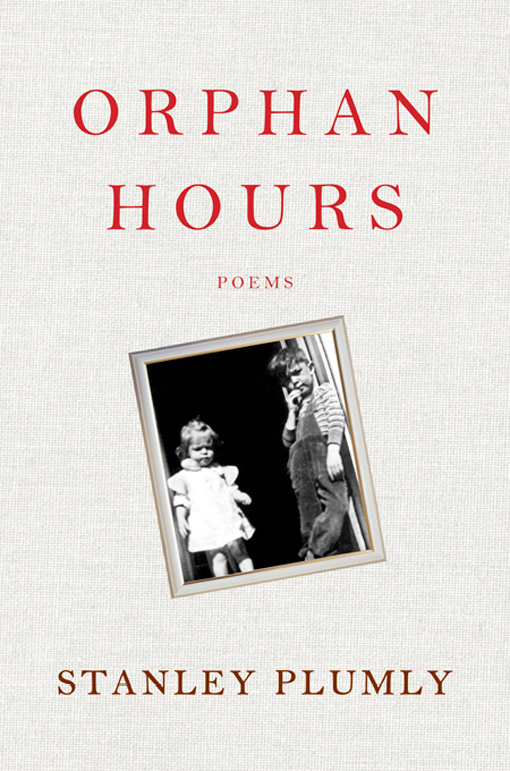

New and Selected Poems, 19702000 The Marriage in the Trees Boy on the Step Summer Celestial Out-of-the-Body Travel Giraffe How the Plains Indians Got Horses In the Outer Dark NONFICTION Posthumous Keats Argument & Song: Sources & Silences in Poetry Orphan Hours POEMS Stanley Plumly W. W. NORTON & COMPANY  NEW YORK LONDON for Michael Collier Jan 1. 1821 Hours hours Pale cold Orphan hours SHELLEY Contents On Deciding Not to Be Buried

NEW YORK LONDON for Michael Collier Jan 1. 1821 Hours hours Pale cold Orphan hours SHELLEY Contents On Deciding Not to Be Buried

but Burned Amidon Christmas Tree

Farm Cardinal Sitting Alone in the Middle

of the Night The Day of the Failure in Saigon,

Thousands in the Streets, Hundreds

Killed, A Lucky Few Hanging On the

Runners of Evacuating Copters Dusk Coming On Outside

, New York Acknowledgments Thanks are due the editors of the following magazines in which poems in this volume were originally published, many of which have undergonesometimes radicalrevision. The American Poetry Review, Antaeus, The Atlantic, Connotation Press, The Gettysburg Review, Gulf Coast, Harvard Review, Haydens Ferry Review , The Hopkins Review, The Kenyon Review, The New Republic, The New Yorker, The Ohio Review, and Poetry Northwest. W. W.

Norton, 1970. As Reported: Paraphrase and quotations are from Jonathan Franzens Emptying the Skies, The New Yorker, July 26, 2010. Canto XVIII: originally published, in different form, in Dantes Inferno: Translations by 20 Contemporary Poets, ed. Daniel Halpern, Ecco, 1993. Human Excrement and Dusk Coming On Outside , New York first appeared, in different form, in Poems for a Small Planet: Contemporary American Nature Poetry, eds. Robert Pack and Jay Parini, University of New England Press, 1993.

The Lost Wine is freely adapted from Paul Valrys Le Vin Perdu, Posies, Gallimard, 1942. Versions of Ground Birds in Open Country and Verisimilitude appeared as broadsides designed by Michael Kaylor and Richard Russell respectively. The epigraph is from one of Shelleys Notebook entries among the Bodleian Shelley Manuscripts as quoted in Ann Wroes remarkable biography Being Shelley: The Poets Search for Himself, Pantheon, 2007. Appreciation to Lindsay Bernal for the preparation of the manuscript. And to the University of Maryland whose support made completion of this book possible. Lapsed Meadows Wild has its skills.

The apple grew so close to the ground it seemed the tree was thicket, crab, and root, and by fall would look like brush among the burdock and the hawkweed, as if at heart it had been cut and piled for burning. Along the edges, at the corners, like failed fence, the hawthorns, by comparison, seemed planted. Everywhere else there was broom grass, timothy, and wood fern, and sometimes a sapling, sometimes a run of hazel; sometimes, depending, fruit still green or grounded and rotting underfoot. I remember, in Ohio, fields of wastes of nature, lost pasture, fallow clearings, buckwheat and fireweed and broken sparrow nests, especially in the summer, in the fading hilltop sun, when you could lose yourself by simply lying down. Who will find you, who will call you home now, at dusk, with the dry tips of the goldenrod confused with a little wind, filling in whats left of the light? The Crows at 3 A.M. The politically correct, perfect snow of Vermont undulant under the lightly bruised, moonlit-backed becoming-storm-clouds slowing then speeding just above the lines of blue spruce on Mount Mansfield here in what Im told is the states cloudiest county, vaguely an analogy for the plate tectonics of the blankets constantly shifting from the left to the right side of my body, pulling the heart, until by dawn Im holding on, waking with the cold, somehow looking at my hands in the pearl dark that look like the first fall-castings of the sycamore, those pocked dry leaves that were my mothers final hands: sallow dying coloring, mapping liverspots, rootlike veining texturing the underdermal surfaces.

The test, writes Fitzgerald, in an essay called The Crack-Up, of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold opposing ideas in the mind at the same time yet retain the ability to function. He couldnt, he says, so he cracked like a plate. He is trying to update Keatss notion of Negative Capability, that is when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reasonColeridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge. When I heard the crows, like raven-geese, rending the dark, filling the falling snow with wings, I thought, for a moment, they were speaking or singing. Crows at the hourFitzgerald againof a dark night of the soul, Poe-like crows chasing back and forth in a quandary or a quarrel, up and down the Gihon. Then they disappeared, let me drift back into sleep to find my hands holding my mothers hands as if to help her rise from the cold dead dream light of Vermont.

Stevens twenty or so blackbirds may differ in their scale, but their beauty of inflections and innuendoes is no less present in the settled order, passing out of hearing, out of sight. Thus the rivers moving, the blackbird must be flying, two half knowledges or halves of one knowing. Those who love us who now live in the air live in a loneliness we can only imagine. The Jay He does not lie there remembering the blue-jay, say the jay. S TEVENS In white Adirondack chairs, on the wave-crest of a dune, looking out over the gray-green-to-cobalt-colder-blue of the Atlantic, drinking decadence in large Barolo portions, taking in, like sea-air, the view and ocean silence, its difficult to imagine not being here, or, worse, never being here again, or, worse, never having been here. My mother never saw an ocean, and Wallace Stevens never traveled except by Pullman to Key West and all the stops between.

He speaks, in Madame La Fleurie, of his mother as the raven waiting parent, though mother also means the earth, welcoming the child back to the beginning and end. Naturally the sun is falling, which had risen in first light only this morning, burning its stunning star-path perfect to this place of witness. Now that its a rose disintegrating, in all the colors of the spectrum all at once, we can look at it the way it is, on fire. The way, too, the big male of a blue jay on the snow fence to the right, watching with us, waits for the dark or what passes for the dark, a kind of water-surface blue, and the second the sun is gone hes gone just over us, a few feet at the most, likely into the safety of a hedge. Wed been imagining the need to recognize the moments moment before it disappears, as if you could know a thing before it happens, life in the future tense, when, in fact, like sunlight on the water here and there, we live in one time but think in another. We were, if not exactly, close to drunk, so we lifted to the light our full glasses.

The jay was beautiful. Especially in the air, blue on blue, his white wing-spots and white touch on the tail shining in that instant of the sun slipping under. Not once, in his happiness or reverence or indifference, did he sing, complain, or say anything. He flew on a line drawn in time from now to then. I can still see him, though finally he was nothing but a blur inside the death of everything that happens. My Lawrence The future, rain in every syllable and cell, comes home later and later, until its half past morning and time to go to work all over again.

David Herbert Lawrences collier father working his way toward death in little piecesI could see him in the book as I could hear my own breaking into the house in the dead middle of the night. Work requires a ton and then a lump of coal to build up fires like a setting sun you look at and call nature, beautiful furnace fires that turn back flesh to smoke and ash, back to the drift and ghost it comes from. Read everything, the English teachers saidI read Lawrence first at a big oak dining table in a Quaker reading room, though not, I think, the novels but something more like Studies in Classic American Literature, literature abridged sometimes for children, which Lawrence takes seriously: Irvings bowling Dutchmen, Coopers noble savages, Poes still living dead, Melvilles South Sea natives and God in a white whales head, even Hawthornes scarlet letter worn as a final warning in a fundamental Boston surrounded by the treesbrilliant analyses, written like short stories, stories like his poems or his strange travel essays or his blood-dark archetypal fiction, memory when memory fails. Thus his imagined father in firelight at the fireplace, having at that moment the overwhelming thought that this is what his life has come to, a passage between impossibilities, morning and evening, climbing the ladder into the earth, climbing the ladder back. Sons and Lovers, sons and fathers, childrens stories by the time I got to Paul Morel, the Bottoms and Hell Row and the tiny, bricky, garden-patched rowhouses, now part of Greater Nottingham, got there literally, too, early in the sixties, in search of where he started, before his own search for self sent him to Australia, America, and Italy, I thought I understood how much we feel alone in the company of fathers, how work itself is a father: the scene in Women in Love when Gerald Crich dives to save his sister and her lover, who lie in an embrace at the bottom of a pond, among a living world of mud and growth and stone, dives again and again.... Crich walks finally out of the water covered, alone, and says theres room for thousands down there.

Next page

ALSO BY STANLEY PLUMLY POETRY Old Heart Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me:

ALSO BY STANLEY PLUMLY POETRY Old Heart Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me: NEW YORK LONDON for Michael Collier Jan 1. 1821 Hours hours Pale cold Orphan hours SHELLEY Contents On Deciding Not to Be Buried

NEW YORK LONDON for Michael Collier Jan 1. 1821 Hours hours Pale cold Orphan hours SHELLEY Contents On Deciding Not to Be Buried