PENGUIN CANADA

THE SHEIKHS BATMOBILE

RICHARD POPLAK is the author of the acclaimed Ja, No, Man: Growing Up White in Apartheid-Era South Africa. He has written for, among others, The Walrus, THIS Magazine, Toronto Life, and The Globe and Mail and has directed numerous short films, music videos, and commercials. He lives in Toronto.

ALSO BY RICHARD POPLAK

Ja, No, Man: Growing Up White in Apartheid-Era South Africa

The

Sheikhs

Batmobile

In Pursuit of American

Pop Culture in the

Muslim World

Richard Poplak

PENGUIN CANADA

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 2009

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Copyright Richard Poplak, 2009

All song lyrics quoted in this book are reproduced with permission.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Manufactured in Canada.

ISBN: 978-0-14-305655-3

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data

available upon request to the publisher.

Visit the Penguin Group (Canada) website at www.penguin.ca

Special and corporate bulk purchase rates available; please see

www.penguin.ca/corporatesales or call 1-800-810-3104, ext. 477 or 474

Understanding a peoples culture exposes their normalness

without reducing their particularity.

CLIFFORD GERTZ

If one cannot trust literature, one can at least trust pop culture.

UMBERTO ECO

Homer: The lesson is: Our God is vengeful!

O spiteful one, show me who to smite and they shall be smoten!!!

THE SIMPSONS

AUTHORS NOTE

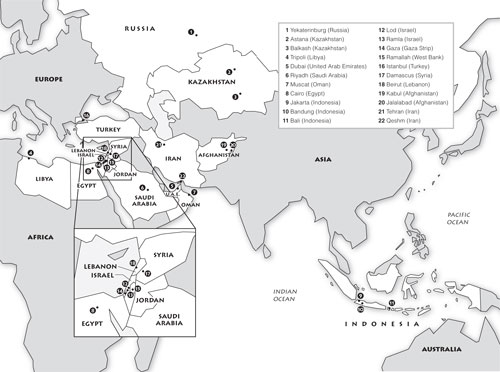

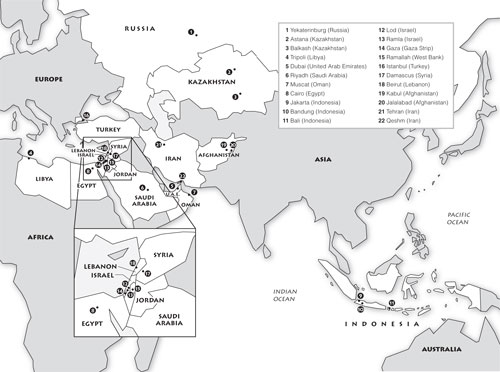

I travelled to seventeen countries in the course of my research. I mention this not to impress you, but rather to point out that while over half counted Arabic as their lingua franca, it is by no means a standardized language and regional dialects differ greatly. Even in Iran, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Turkey, Arabic peppers local languages, so strong is the influence of Arab/Islamic culture. This can become confusing, and there is no standardized transliteration style guide for Arabic or Bahasa or Pashtu or any of the tongues I encountered during my research. I have rendered words as they sounded to my ear. Others may, and indeed have, chosen to represent them differently.

Over two hundred people were interviewed for this book. I mention this not to astound you, but to make clear that while not all of them made it into these pages, many of them took great personal risk in speaking to me. If I did include their testimony, in some cases they asked me not to use their name; in other cases I have decided not to. I have made this obvious in the text by providing appellations. Wherever necessary, I indicate that my sources are anonymous.

Speaking of impressed and astounded, I came to admire the enormous courage exhibited by so many of the artists I met during my months of research. Their steadfast refusal to abandon their work in the face of insurmountable challenges has been a constant inspiration. I offer this book as a dedication to them and hope that they accept it as such (whether or not they agree with the positions I have arrived at, or I with theirs). They affected me in the way beautiful pop songs or perfect Hollywood movies do: They gave me a reason to believe in the future. Hope has become something of a cheeseball buzzword of late, but Id be lying if I said I didnt come away from my journey full to brimming with it. And for that, I cannot thank them enough.

T he functionary leaned in. He smelled like dust and formaldehyde, his suit jacket large enough for an adult grizzly. Outside, under a chemical-spill sunset, the brand new Kazakh city of Astana glittered like a gaggle of teenaged drag queens dressed as Tammy Faye Bakker.

You say the question again, said the functionary through lips as thick as bicycle tires. He meant this as a warning. Grabbing another small glass of vodkahis seventhfrom a passing waiter, he glared at me warily.

I was badly unhinged. For the past two days, I had sped across the northwestern steppes of Kazakhstan, cruise control set to eighty miles an hour. Time moved like stretched putty, dragging day into icy night over tremendous, Fruit Loophued gloamings. Decaying granaries were visible for miles, while fathoms of dead earth were interrupted only by futurist signs for what sounded like all-you-can-eat Chinatown buffets: Happiness Peoples Combination or Togetherness Food Creation.

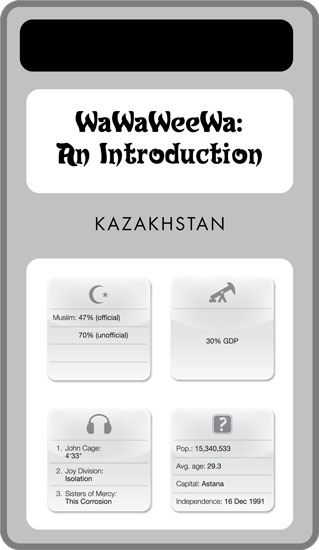

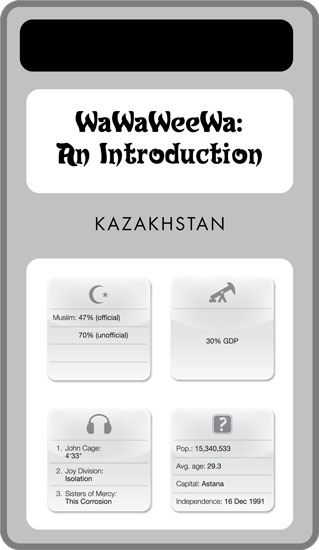

Racing through a country the CIA World Factbook lists as roughly four times the size of Texas, I inadvertently followed the path of Islam as it spread from Arabia into Central Asia circa AD 700. Now it was a land of chronic pollution and quiet faith, seventy percent Islamic, one hundred percent bewildered. Nursultan A. Nazarbayev, President for Life and an ally of the Bush administration, had banned the form of Islam practised by most of Kazakhstans Sunni Muslims. Pundits eyed the region, waiting for a Red Martyrs Wheat Brigade or an al-Qaida Socialist Workers Collective to leap forth, bomb-belts blazing. Handshakes were proffered, weapons delivered, deals struckanything to avoid the opening of another front along the resource-rich Caucasus.

The functionary swayed on his feet. It was becoming increasingly important that I explain to him that I meant no offence. He seemed to blame me for the public relations debacle that had recently stricken his country, as vicious and arbitrary as an outbreak of bubonic plague. I had arrived in Kazakhstan on the unhappy eve of the North American release of Sacha Baron Cohens Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. It was a film that no countrynot even an ex-thermonuclear bomb-testing facilitywould want to be associated with. This was bad for branding, the equivalent of discovering that a new processed meat product causes not only gastric cancer, but also halitosis, memory loss and erectile dysfunction.

Next page