My gratitude to the following people for their help, confidence, and belief in me:

Margaret Bail, my agent, who saw the potential and took a chance on me where no one else would.

Walt Pavlo, Jr., who has walked a mile in my shoes, stumbled, and continued on.

Paul Reinhertz, my brother, my friend; words cannot reach the depth of my gratitude for what youve brought to my lifetrue friendship.

Melissa, none of this would be possible without your help. Thank you for not only believing in me, my work, and my wordsbut in the memory of that teenager you once knew, and recognizing hes still here. And finally, for helping me to understand there are second chances in life, love, and happiness.

FOREWORD

I spent time in a federal prison camp for a white-collar crime from 20012003. There is no pride in this proclamation, but it is through that experience that I have talked and written on white-collar crime for the past twelve years.

In September of 2011 I became a Contributor to Forbes.com and have interviewed insider traders, embezzlers, defense attorneys, prosecutors, and family members of inmates. In my work I attempt to create a mosaic of the people involved in our criminal justice system so that the general public understands how these crimes are perpetrated, who perpetrates them, how they are discovered, and the resulting punishment.

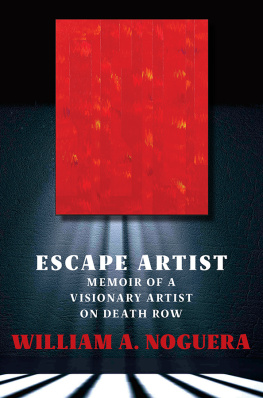

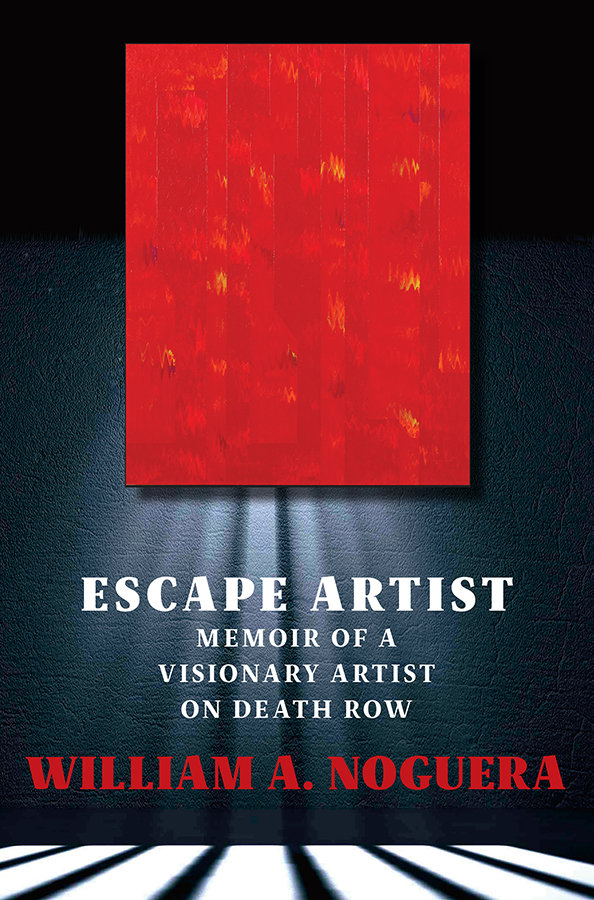

On reflection, my reasoning for digging deeper into white-collar criminal law has been as much about a search for self as it has been about an interest in the many cases that I cover. So I have been dedicated to understanding everything I can about the topic, the people, and the law. Then I met William A. Noguera, a man living a quarter of a century on San Quentin State Prisons death row.

On June 22, 2013, I walked through the gates of San Quentin State Prison just north of San Francisco. I was going to visit Noguera, a man sentenced to death in 1987 for a murder committed some years earlier. At the sentencing he was all of twenty-three years old and he had been in prison since he was nineteen. While I was interested in the case against him that resulted in the ultimate punishment, I was drawn to Noguera by his intellect, the disciplined life he leads in extreme conditions, and his beautiful art that he creates in the hell that surrounds him.

I was locked in a cage with Noguera for my visit, which is now the procedure for visitation at San Quentins death row since a violent incident between two rival inmates broke out during visitation in 2000. I was allowed to visit for five straight hours and was not allowed to bring in any prepared notes, pen, or paper. I had wondered if I had five hours worth of conversation in me with a man on death row, whom I had spoken with only a number of times via phone prior to that visit. It turned out that five hours was not enough time.

I left San Quentin that day wondering if I would ever see Noguera again or how I might further pursue telling his story. It was a long flight back to Boston, and in the following months I thought of William, his art, and our visit together. He left a lasting impression on me.

As I read a draft of this book, I recognize the man and the artist that I visited with in San Quentin. His transparency, acceptance of responsibility, and his passion for art come through with every word. He takes us along a journey of his life that is reflected in his own words and, more importantly, through his art.

After getting to know Noguera, reading this book, and viewing his art, his life continues to make me ponder deeper questions I have about my own life. First, can a person be seen for the good that they do now, no matter the wrong they have done in the past? This question is not one of forgiveness, it is about our ability to accept the good in the world without judgment. Was Picasso a saint? No, nor is Noguera. Yet we are able to look upon works by Picasso without analyzing the faults in his life. Art should transcend our ability to judge a person beyond what is on the canvas.

Second, how does a person live an ethical life in the face of daily challenges to conform with the unethical, the savage? Each semester I teach an Ethics class to MBA students at Endicott College, just north of Boston. Noguera calls in to the class and shares the surroundings he lives in and how he overcomes the temptations against falling into the demonic life of fellow inmates. For our students, it provides a view of a man in the midst of ethical temptations that go on in perpetuity. However, Noguera offers hope to those students, insight and love from a place that is void of it. Our students have embraced the experience.

The third question that I have has to do with my own limitations in understanding art. Is Noguera a brilliant artist, or is he simply a good artist who is in prison? I have sat and looked at his paintings for hours and have been moved to tears. His ink-stippling pieces look like photographs and each tells a story. His abstracts are full of color, and I have enjoyed conversations with him as he described each piece in detail, though they had left his cell many years before. Is he an art master? I do not know, and Noguera himself wants to know. He wants to be judged by peers in the art world, critiqued, talked about, but he wants it to be based on his art, not the circumstances of his life.