Stephen Potter was born in 1900 and educated at Westminster School and Merton College, Oxford, where he read English. In 1926 he became a lecturer in English at London University, and in 1938 he joined staff of the B.B.C. as a writer-producer. There he became editor of literary features and poetry, and in 1943 Chairman of the Literary Committee. His principal programmes were the How series (with Joyce Grenfell) and the Professional Portraits, and he was originator and editor of the New Judgement series. He was also dramatic critic of the New Statesman, book critic of the News Chronicle and editor of the Leader Magazine. Stephen Potter died in 1969.

To Francis Meynell

THE THEORY

AND PRACTICE OF

GAMESMANSHIP

OR

THE ART OF WINNING GAMES

WITHOUT ACTUALLY

CHEATING

BY

STEPHEN POTTER

ILLUSTRATED BY LT.-COL.

FRANK WILSON

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Reader

Bloomsbury Reader is a division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square,

London WC1B 3DP

First published in Great Britain in 1947 by Rupert Heart-Davis

Copyright 1947 Stephen Potter

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise

make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means

(including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying,

printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the

publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The moral right of the author is asserted.

eISBN: 9781448212378

Visit www.bloomsburyreader.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for

newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

Contents

1

Introductory

If I have been urged by my friends to take up my pen, for once, to write of this subject so difficult in detail yet so simple in all its fundamental aspects I do so on one condition. That I may be allowed to say as strongly as possible that although my name has been associated with this queer word gamesmanship, yet talk of priority in this kind of context is almost meaningless.

It is true that in the twenties certain notes passed between H. Farjeon and myself. But equally notes passed between H. Farjeon and F. Meynell. It is true that in March 1933 I conceived and wrote down the word gamesmanship in a letter to Meynell. Speaking of a forthcoming lawn tennis match against two difficult opponents, I said we must employ gamesmanship.

It is true also that I was the most regular visitor chairman would imply a formality which scarcely existed in those early days of argle-bargle and friendly disagreement at the meetings which took place in pub parlour or empty billiard hall between G. Odoreida, Meynell, Wayfarer, and myself. It is true that it was in these discussions that we evolved a basis of tactic and even plotted out a first rough field of stratagem which determined the centres of development from which the new technique spread in ever-widening circles. Small beginnings, indeed, for a movement which has spread so far from the confines of the country, and has shown itself too big to be contained by the World of Games for which it was fashioned.

But after the first formulation the spade-work was certainly done as much by Meynell and a few other devoted collaborators as by myself. And how well wise after the event we realize, now, from his practice and example, that Farjeon had the gist of the thing under his nose the essential factors, the actions and reactions of the whole problem, without having the luck to see the patterning alignment, the overall theory, which made them make sense.

And yet had it not been for the dogged spadework of Farjeon in the middle twenties, we should none of us now be enjoying the advantages of a theory which devolves as naturally from those meticulously collected data of his as Rutherfords enunciation of atomic structure derived from the experiments of that once obscure chemist Mierff.

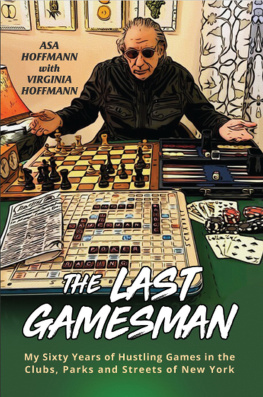

What is gamesmanship? Most difficult of questions to answer briefly. The Art of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating that is my personal working definition. What is its object? There have been five hundred books written on the subject of games. Five hundred books on play and the tactics of play. Not one on the art of winning.

I well remember the gritty floor and the damp roller-towels of the changing-room where the idea of writing this book came to me. Yet my approach to the thing had been gradual.

There had been much that had puzzled me I am speaking now of 1928 in the tension of our games of ping-pong at the Meynells. Before that there had been the ardours and endurances of friendly lawn tennis at the Farjeons house near Forest Hill, where Farjeon had wrought such havoc among so many visitors, by his careful construction of a home court, by the use he made of the net with the unilateral sag, or with a back line at the hawthorn end so nearly, yet not exactly, six inches wider than the back line at the sticky end. There had been a great deal of hard thinking on both sides during the wavering tide of battle, ending slightly in my favour, of the prolonged series of golf games between E. Lansbury and myself.

But it was in that changing-room after a certain game of lawn tennis in 1931 that the curtain was lifted, and I began to see. In those days I used to play lawn tennis for a small but progressive London College Birkbeck, where I lectured. It happened that my partner at that time was C. Joad, the celebrated gamesman, who in his own sphere is known as metaphysician and educationist. Our opponents were usually young men from the larger colleges, competing against us not only with the advantage of age but also with a decisive advantage in style. They would throw the service ball very high in the modern manner: the back-hands, instead of being played from the navel, were played, in fact, on the back-hand, weight on right foot, in the exaggerated copy-book style of the time a method of play which tends to reduce all games, as I believe, to a barrack-square drill by numbers; but, nevertheless, of acknowledged effectiveness.

In one match we found ourselves opposite a couple of particularly tall and athletic young men of this type from University College. We will call them Smith and Brown. The knock-up showed that, so far as play was concerned, Joad and I, playing for Birkbeck, had no chance. U. C. won the toss. It was Smiths service, and he cracked down a cannon-ball to Joad which moved so fast that Joad, while making some effort to suggest by his attitude that he had thought the ball was going to be a fault, nevertheless was unable to get near with his racket, which he did not even attempt to move. Score: fifteen-love. Service to me. I had had time to gauge the speed of this serve, and the next one did, in fact, graze the edge of my racket-frame. Thirty-love. Now Smith was serving again to Joad who this time, as the ball came straight towards him, was able, by grasping the racket firmly with both hands, to receive the ball on the strings, whereupon the ball shot back to the other side and volleyed into the stop-netting near the ground behind Browns feet.

Now here comes the moment on which not only this match, but so much of the future of British sport was to turn. Score: forty-love. Smith at S1 (see Fig. 1) is about to cross over to serve to me (at P). When Smith gets to a point (K)