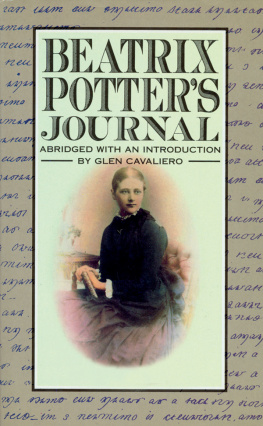

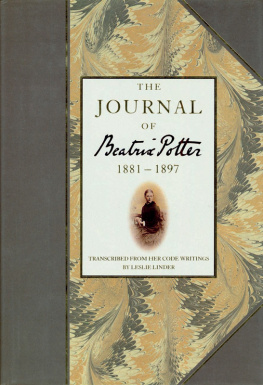

BEATRIX POTTERS JOURNAL

Abridged with an Introduction by Glen Cavaliero

Frederick Warne

FREDERICK WARNE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

The Journal of Beatrix Potter from 1881 to 1897 first published 1966

This abridged edition first published 1986

Journal copyright Frederick Warne & Co., 1966

Introduction and abridgement copyright Glen Cavaliero, 1986

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

ISBN: 978-0-72-326558-0

Contents

List of Plates

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

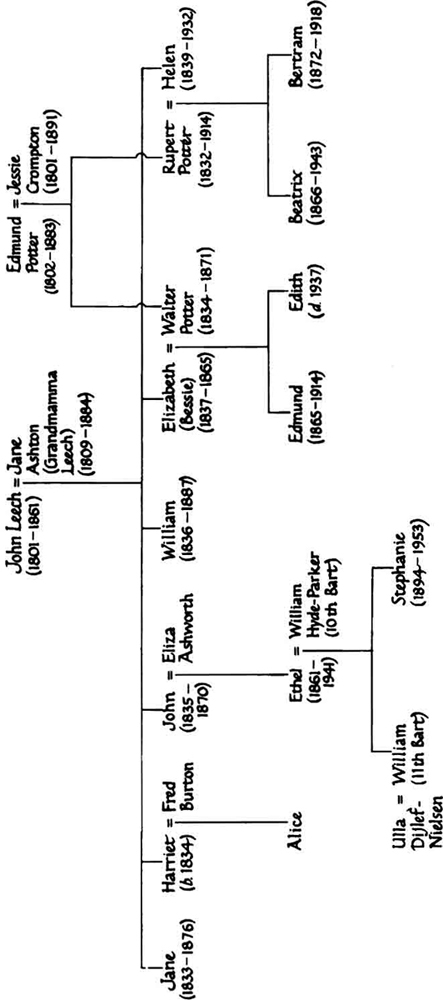

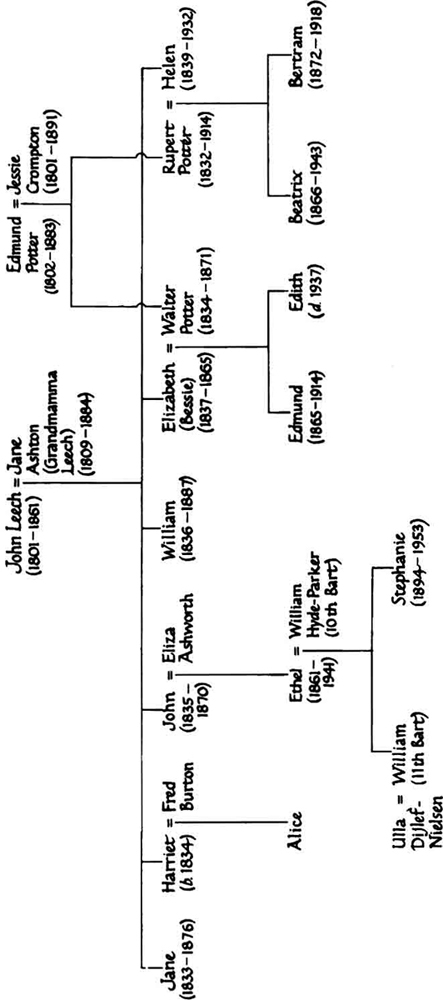

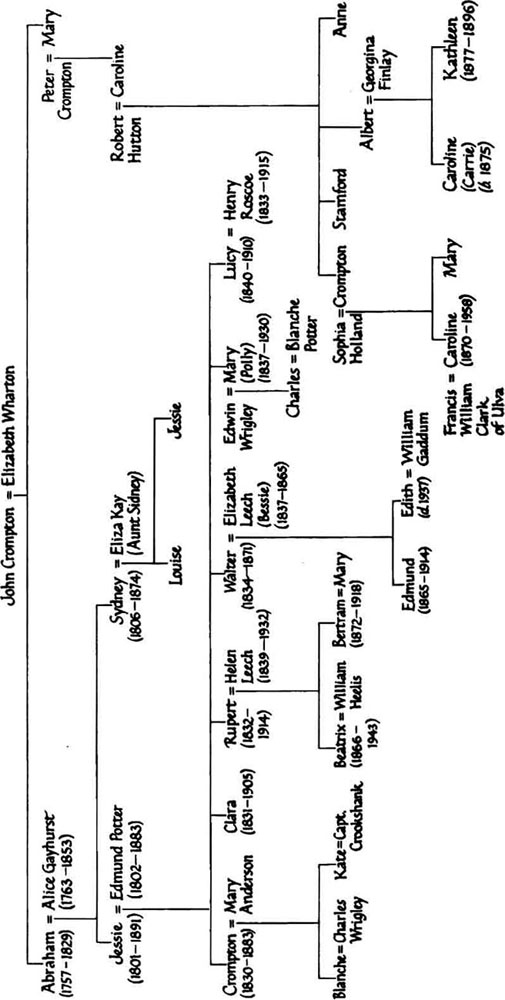

Leech Family Tree

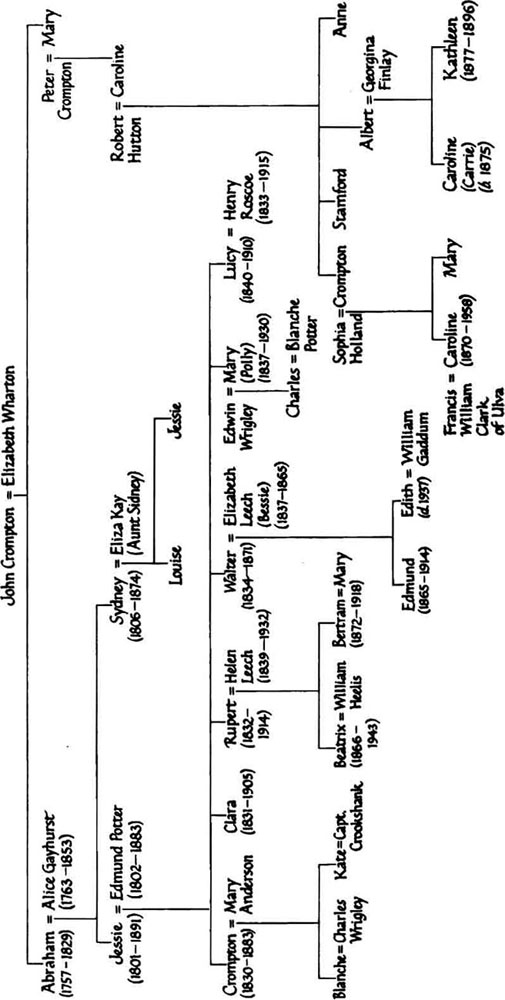

Potter and Hutton Family Tree

Acknowledgements

Among those who have helped me in the preparation of this book I would like especially to thank Mr Eugene Fisk, Mr David Lowe, Mr John Skidmore and Miss Judy Taylor.

Note on the Text

Apart from making two or three small amendments I have followed Leslie Linders text throughout (The Journal of Beatrix Potter, 188197, Warne, 1966). No individual sentences have been abridged, but, in the interest of continuity, paragraph units have been retained without the use of spaced dots to indicate omissions. I have added a number of footnotes: the remainder are by Leslie Linder, and carry his initials. A few of these have been shortened. The family trees have been simplified, the more easily to locate people mentioned in the Journal.

Introduction

Few twentieth-century English writers have been so continuously popular as Beatrix Potter. The twenty-one small tales she wrote for children, all but two of them published before 1914, are held in undiminishing affection by successive generations of readers. Her work has been translated into a dozen different languages, including Swedish, Afrikaans and Japanese; and people of all ages and nationalities make the journey to her farmhouse in the English Lake District. Such an accolade seems out of all proportion: the books are short, designed specifically for children, and intensely local in their style and setting. And yet her appeal transcends these limitations. She herself, with the arrogance proper to a genuine artist, had no doubt as to what she had achieved, confiding to one of her relations that she knew her stories were as sure of immortality as those of Hans Andersen. Indeed, it is only a snobbery concerning scale that would find her books too small to warrant serious consideration. For they do warrant it: they are far more than merely childrens books. They exert a lasting influence upon their readers, a spell which is at once familiar and mysterious. Beatrix Potters Journal not only throws light on how the books came to be written, it goes some way to accounting for their particular appeal.

Beatrix Potter was born in London in 1866 at a time of prosperity and confidence, halfway through Queen Victorias reign. Overseas, British power and influence were strong. At home, more and more middle-class people were able to live off unearned incomes: money had become self-propagating. The average home became more comfortable and filled with furniture and other forms of portable property. In the world of art the Pre-Raphaelite school of painters, with their microscopic attention to detail, backed by the powerful advocacy of John Ruskin, were encouraging other artists to produce pictures that were celebrations of the visible world and appealed strongly to prosperous families like the Potters. In the field of literature, Tennyson was Poet Laureate: his work, too, was full of meticulous, detailed observation, and his popularity was a measure of public taste. Architects, on the other hand, favoured the grandiose and the monumental: public buildings reflected a hopefulness about the future which typified the age.

At the same time, a programme of electoral and educational reform was under way which in due course would partly undermine the hierarchical ordering of society. A year after Beatrix Potter was born the Second Reform Act all but doubled the electorate; three years after that the Education Act of 1870 inaugurated universal elementary education. By 1881, when Beatrix began to keep her Journal, British prosperity was being threatened by competition in world markets, Home Rule for Ireland was an issue that had erupted into violence, while terrorism was a growing threat to European stability. Imperial policies led to unfortunate military entanglements; scientific discovery was undermining the grounds of religious belief. It was a time of gradually increasing uncertainty and unrest, as society attempted to absorb the shock of new discoveries and the decay of long-established institutions.

Beatrix Potters Journal reflects the thoughts and reactions of a clear-sighted young woman between the ages of sixteen and thirty, whose secure but unusually solitary life enabled her to respond with absolute integrity to what she heard and saw. Changes were in the air which would affect her attitudes; unconsciously, she was changing too. Outwardly she may have seemed undisturbed, but in her Journal she reflects an anxiety about her times as well as doubts about her own future.

Her birthplace, Number Two, Bolton Gardens, stood at the end of a terrace of gloomy five-storey houses in West Brompton, which at that period was a prosperous residential district. The road was not far from the two great South Kensington museums, the Victoria and Albert Museum, dedicated to the arts and sciences, and the Natural History Museum. Both were expanding while she was growing up, and both helped to form the tastes and interests of the girl whose work would one day be exhibited in the former, and who was to live in Bolton Gardens for nearly fifty years. Beatrix had little love for the house and was quite untroubled when she heard of its destruction in the air raids of the Second World War. It was a vertical, stratified house, with the servants inhabiting the basement and attics, the master and mistress presiding on the ground and first floors, and the children kept out of the way at the top. Inevitably such terrace houses were dark, and Victorian taste in furnishing and decoration made them darker still. Beatrix Potter, whose books are full of a sense of the country, of living, breathing things, and fresh air and hilly landscapes, grew up in a home in which a strict routine kept everything and everyone in order and whose only garden was a small square of grass. Such self-imposed predictability was essential for people of the Potters social standing, if they were to make a life of unbounded leisure seem morally respectable.