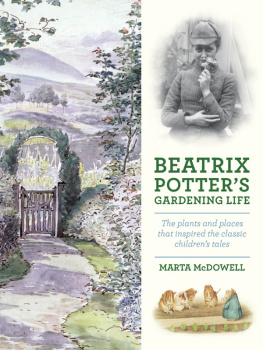

BEATRIX POTTERS

GARDENING LIFE

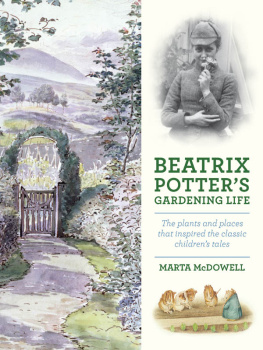

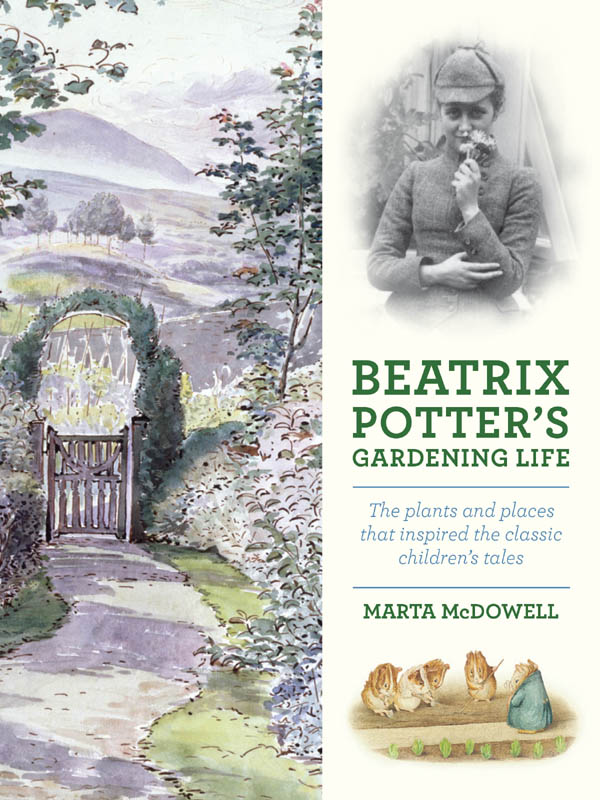

Beatrix Potter on holiday at Holehird, Windermere, 1889

BEATRIX POTTERS

GARDENING LIFE

The plants and places that inspired the classic childrens tales

MARTA McDOWELL

TIMBER PRESS

Portland London

Copyright 2013 by Marta McDowell. All rights reserved.

Frederick Warne & Co. is the owner of all rights, copyrights, and trademarks in the Beatrix Potter character names and illustrations. Unless otherwise noted on (Photography & Illustration Sources & Credits), images used in this book are copyright Frederick Warne & Co., reproduced by permission of Frederick Warne & Co.

Published in 2013 by Timber Press, Inc.

| The Haseltine Building | 6A Lonsdale Road |

| 133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite | 450 London NW6 6RD |

| Portland, Oregon 97204-3527 | timberpress.co.uk |

| timberpress.com |

Printed in China

Book design by Marla Sidrow

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McDowell, Marta.

Beatrix Potters gardening life : the plants and places that inspired the classic childrens tales / Marta McDowell.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-363-8

1. Potter, Beatrix, 1866-1943. 2. Potter, Beatrix, 1866-1943Homes and hauntsEngland. 3. GardensEngland. I. Title.

PR6031.O72Z74 2013

823'.912dc23

2013001143

A catalog record for this book is also available from the British Library.

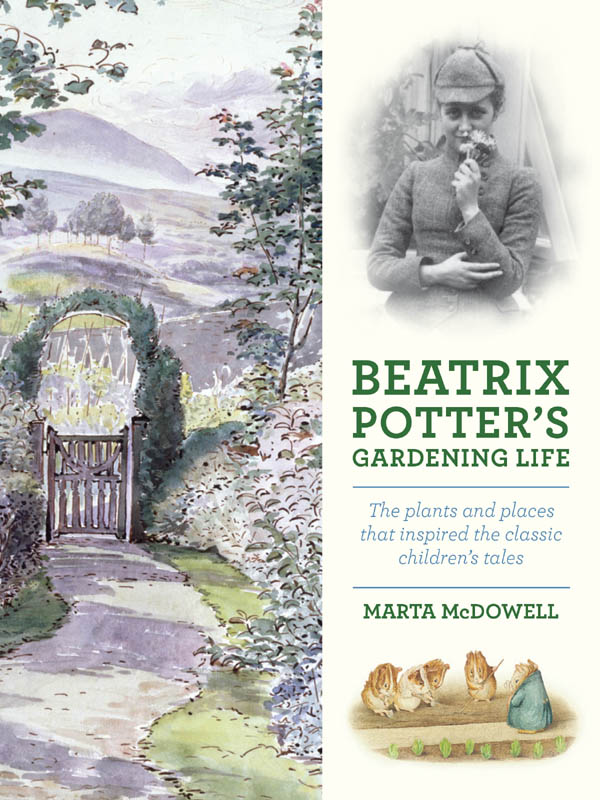

Guinea pigs gardening from Cecily Parsleys Nursery Rhymes

For Kirke

CONTENTS

THE FLOWERS LOVE the house, they try to come in. The golden flowered great St. Johns wort pushes up between the flags in the porch, it has peeped up between the skirting and the flags inside the porch place before now. And the old lilac bush that blew down had its roots under the parlour floor, when they lifted the boards. Houseleek grows on the window sills and ledges; wisteria climbs the wall; clematis chokes the spouts casings. Wall flowers and cabbage roses in season; rosemary and blue gentian, and earliest to flower the red pyrus Japanese quincebut nothing more sweet than the old pink cabbage rose that peeps in at the small paned windows.

Beatrix Potters description of Hill Top, part of an unpublished sequel to The Fairy Caravan

PREFACE

F IRST, A CONFESSION. I did not read Beatrix Potter as a child. In fact, I learned about Peter Rabbit from a knockoff of sorts. The spoiled youngest of four, I would steadily pester my mother for books on outings to Woolworths, and one day she bought me a shiny-covered Golden Book called Little Peter Cottontail by Thornton W. Burgess. Its naughty rabbit cavorted in wildflowers and visited a farm, but never found Mr. McGregors garden. My introduction to Beatrix Potter came much later in life.

In 1981, at a shower celebrating my upcoming nuptials, someone gave me a large cookie jar in the shape of a bonneted, apron-bedecked porcupine holding an iron. Wedding showers are awkward at best, particularly for learning about famous characters from childhood literature that one has somehow, in two-plus decades of life, managed to miss. What did I say when opening this gift in front of a sizeable, entirely female audience of friends, family, and future relations? That memory is lost. I have also repressed the identity of the gift-giver. Neither the Mrs. Tiggy-winkle cookie jar (a hedgehog, if you please) nor the marriage lasted long.

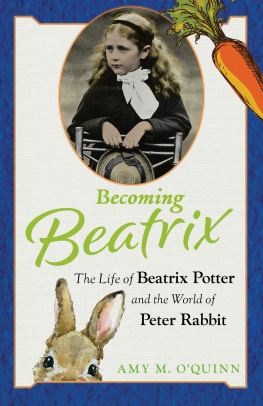

Fast-forward to 1997, when I set off with my second (and last) husband and two aged parents for a tour of Scotland and the Lake District. William Wordsworth was on our agenda. His homes, Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount, are both near Grasmere and not far from Windermere, where we were staying. And what of Beatrix Potter, that childrens author and artist?

Our visit to Hill Top Farm, Miss Potters beloved home on the other side of Windermere, turned out to be a highlight. For one thing, the sun came out that afternoon after a week of Scotland in the rain. (My mother, who had brought only one pair of shoesmy father would blow-dry them for her every night in our B&Bwas especially grateful.) The Hill Top garden was at its August peak; the tour was engaging.

I learned that day that Beatrix Potter was a gardener. I garden, though some days I feel that I do most of my gardening at the keyboard. I am intrigued by writers who garden and by gardeners who write. The pen and the trowel are not interchangeable, but seem often linked. Emily Dickinson, poet and gardener, has long been an obsession of mine. Edith Wharton interests me, and Jane Austen, both novelists with a gardening bent. I once read all of Nathaniel Hawthorne, winnowing his words for horticultural references. Gertrude Jekyll and Vita Sackville-West also oblige. And now there was Beatrix Potter.

A rabbit sets off to garden, later adapted for Peter Rabbits Almanac for 1929

So Beatrix Potter and the idea of her garden simmered quietly at the back of my mind. Over the years I saw some of Potters marvelous botanical watercolors at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. Miss Potter, a Hollywood film, came and went. An adroit article by Peter Parker appeared in the gardening journal Hortus. But one day at the New York Botanical Garden shop, two books lay side by side on a display table: a new edition of Potters The Complete Tales and Linda Lears biography, Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature. The simmer turned to a boil.

A few explanatory notes. You may be relieved or perturbed, depending on your druthers, that I have avoided botanical names in most of the book. Beatrix was not impressed with gardeners Latin, so I have bowed to her feelings on the matter. For those of you who are looking for these particulars, you will find lists of the plants she grew, wrote about, and illustrated, including their proper nomenclature, at the end of the book. Her grammar, punctuation, and spelling were loose, particularly in her letters, but they are reproduced as she wrote them. I would encourage you to have copies of her Tales at hand. The stories with their illustrations are a joy to read. They will increase your understanding of both Beatrix Potter and her gardens.

is a gardeners biography of Beatrix Potter. In terms of her own name, I must beg her pardon on two counts. First, for taking the liberty of referring to her by her Christian name, I plead twenty-first-century customs. Second, during her married years I have generally stuck to her maiden name rather than switching to her preferred Mrs. Heelis. As she continued to use Potter professionally throughout her life, she would, I think, understand that it is by that name that we continue to know her best.

Next page