Copyright 2010 by Robert Michael Pyle

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Pyle, Robert Michael.

Mariposa road : the first butterfly big year / Robert Michael Pyle.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-618-94539-9

1. ButterfliesNorth America. 2. Pyle, Robert MichaelTravelNorth America. 3. North AmericaDescription and travel. I. Title

QL 548. P 944 2010

595.78'9097dc22 2010005763

Linocut on title page by Thea Linnaea Pyle

e ISBN 978-0-547-52785-7

v3.0217

CREDITS

: Excerpt from Old Friends Reunion at Yellowstone, reprinted by permission of John Lane.

To my Thea

AND

to the memory of these ones, all gone too soon, who would have enjoyed the journey:

Harry Foster, Charles Lee Remington, Karlis Bagdonas, MaVynee Betsch, Lee G. Miller, George Austin, Charles Slater, William H. Howe, Barry Sullivan, Larry Everson, George Schiel, and Mike Uhtoff

Finally we learned to know why we did these things. The animals were very beautiful. Here was life from which we borrowed life and excitement. In other words, we did these things because it was pleasant to do them.

John Steinbeck, The Log from the Sea of Cortez (with E. F. Ricketts)

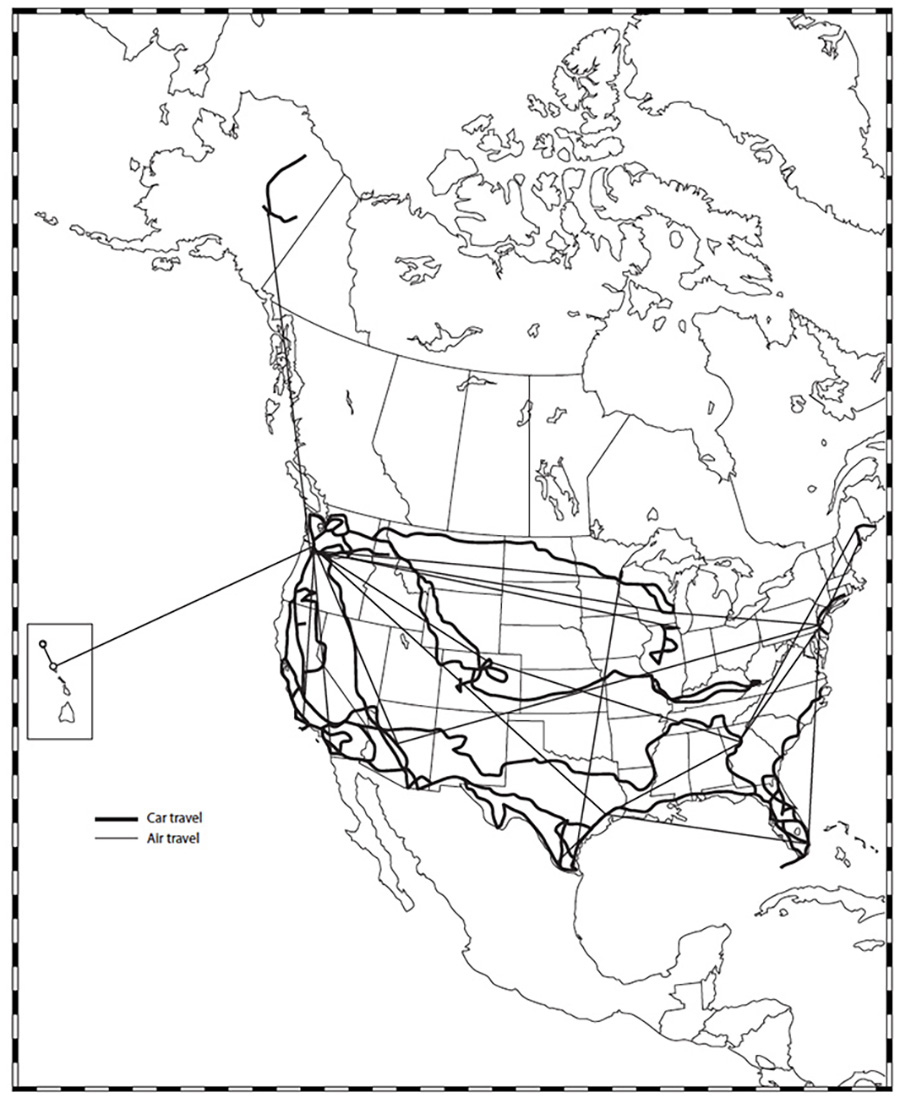

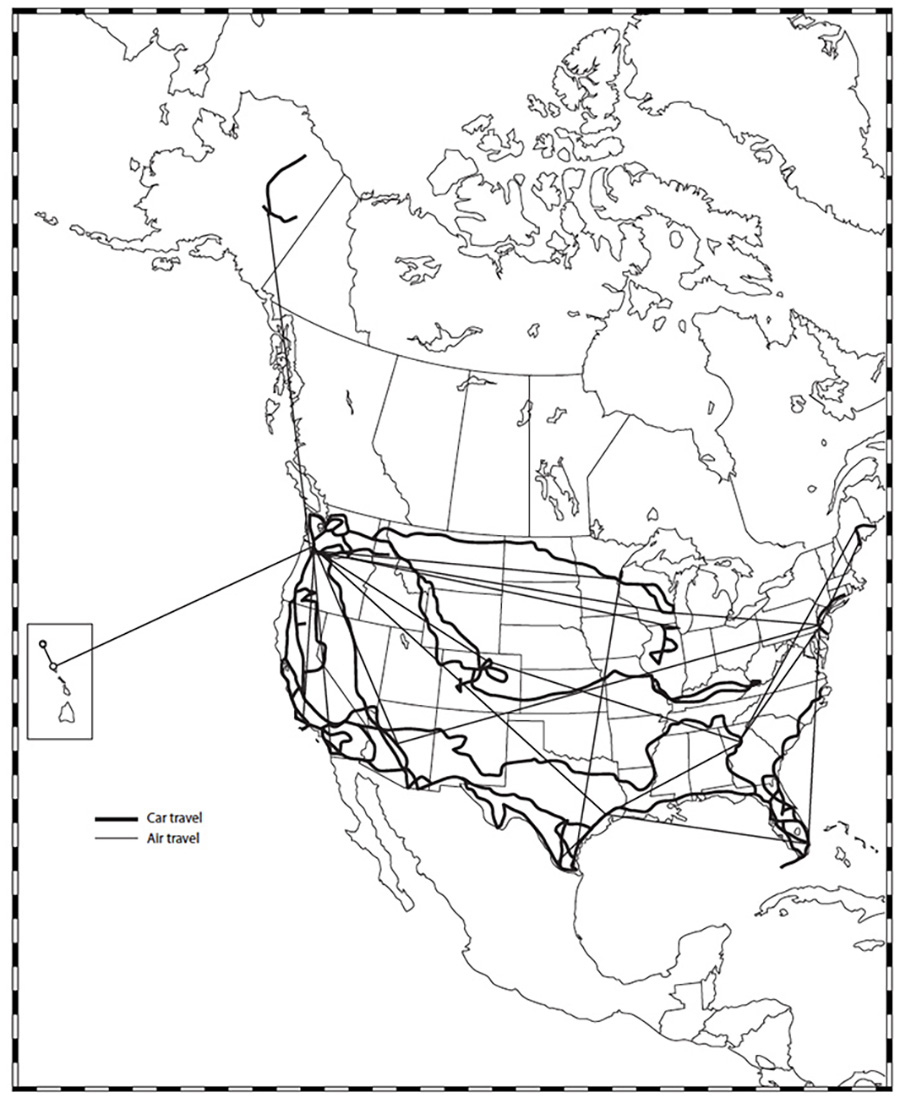

Route map for Mariposa Road

(after S. Jepsen and S. Tenney, Xerces Society)

FOREWORD

Why a Butterfly Big Year?

Late one afternoon in North Florida, I came to a place called Butterfly Knoll. Its faded, split-log archway was painted with a zebra, a monarch, a red-spotted purple, a dogface, and a sulphur. There was no house there now, and just weeds where the garden once grew. What fond fools, I wondered, with what dreams, had come and gone here?

I too was a fool with a butterfly dream: to travel the continent and see as many North American butterflies, north of Mexico, as I possibly could in one calendar year. And why would a person spend a perfectly good year this way? Plastered to the Oregon coast by high wind and rain; driving thousands of miles through desiccated desert boneyards that havent seen a raindrop or a flower for months; slogging through chiggers in an Illinois canebrake in matched heat and humidity in the nineties; crawling prone through icy Minnesota bogs in the snows of Novemberall in search of butterflies?

Otherwise sensible people have attempted birding Big Years for more than half a century. The first great narrative of a Big Year, though the listing itself was so secondary as to be almost a whim, was Roger Tory Peterson and James Fishers wonderful 1955 classic, Wild America. The next was Kenn Kaufmans magical Kingbird Highway. These two books directly inspired the present one. Both fine butterfliers, Peterson and Kaufman attended to some extent to scaled as well as feathered fliers. But neither they nor anyone else, by my reckoning, had ever attempted a butterfly Big Year.

The diversity of American birds and butterflies is roughly the same, but there are profound differences between a Big Year for birds and one for butterflies. Consider the weather: birds fly in the rain and snow, butterflies mostly dont. Or take migration and life span: most butterflies live for a week or two and have strictly limited, frustratingly variable flight periods: if you miss them, you cant pick them up somewhere else, later in the migration, as you can with many birds. But there are similarities too, so a butterfly Big Year ought appeal to birders as well as butterfliersthat is, if anybody ever did one.

My previous book, Sky Time in Grays River, was very much a home book. When I finished it, I found myself hankering after another road romp like the one in Chasing Monarchs, which recounted my 1996 trip to follow the western monarch migration all autumn long. When I suggested the Big Year idea to my literary agent, Laura Blake Peterson, it caught her fancy. We proposed it to Lisa White at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, publisher of Wild America and Kingbird Highway as well as Chasing Monarchs. And when Lisa went for it, there was no turning back.

I saw the project as being somewhat like Chasing Monarchs, only instead of tracking one species in more or less one direction for one season, this would be eight hundred species in every direction for one whole year. Such a broad remit requires a structure, of course, to avoid absolute chaos. So heres the basic setup: my objectives were to find, experience, and definitively identify as many species of butterflies as I could in one full year. The count area would be North America north of Mexico; but unlike the birders, I included Hawaii (they get the offshore waters, useless to me). I would include immature stages (eggs, larvae, and pupae) if identified with certainty, since the adult butterfly is but one-quarter of the animal; birders, after all, count nestlings, and I had no songs to count.

Although I wrote and photographed the first field guide in this country that used photographs of wild butterflies instead of specimens or drawings (Watching Washington Butterflies, 1974), I decided to take no photographs at all. Butterfly photography has evolved, is time-consuming, and would make for a very different experience. I would watch the butterflies and use nets for careful examination in hand when my binoculars were insufficient for the purpose. Usually, this would involve harmless catch-and-release, at which I am adept. However, for difficult species neither at risk nor protected, I would take modest numbers of voucher specimens for expert confirmation and museum deposition. In the event, this practice proved essential for a number of taxa that cannot reliably be identified otherwise. A panel of distinguished lepidopterists would certify my final total.

My methods and tools offered the advantage of simplicity. Unlike many male biologists of my acquaintance, I am neither a gearhead nor a natural mechanic, and I lean seriously toward low-tech. My primary items of equipment were a pair of 6X24 Leitz Trinovid binoculars that I have carried for thirty-five years; an even older companion, a Colorado cottonwood branch-and-hoop butterfly net named Marsha, who has had a hard life (her story is told in Walking the High Ridge: Life as Field Trip); a fine aluminum Japanese net, with extendable handle and collapsable rim, named Akito for the admired lepidopterist who gave it to me; a pocket net named Mini-Marsha; and a basic BioQuip quick-leap-out-of-the-car net; as well as forceps, field notebooks, and mechanical pencils. No laptop, no GPS unitjust a stack of maps and a traveling library of field guides.

My friend Benton Basham, the first Big Year birder to exceed seven hundred species, likes to say that, in a Big Year, strategy is everything. My primary strategies, then, were these: first, I figured that if I went after certain butterflies I considered to be grailsthat is, species Id always wanted to see or see betterthen the more common butterflies would likely fall into the net along the way, as it were. Second, I posited a number of sorties out and back, to and from my home in southwest Washington State. I pictured these outings like the ray petals of a daisy, with Grays River as the flowers disk.

As for tactics, my chief means of travel would be Powdermilk, my 1982 Honda Civic hatchback, which has been a character in several of my previous books, augmented from time to time by rental cars and other vehicles. As for flying, several birding Big Years in recent times have taken great advantage of air travel. I had neither the money nor the desire for that. I would make several flights, particularly to Alaska and Hawaii; but for these, I would exclusively use frequent flier miles or tickets donated by kind supporters. Train travel for several legs would likewise be done with Amtrak miles I had saved. On the whole, I would go solo; but my wife and field pal, Thea, would join me for some of the best bits.