Source acknowledgments for previously published material appear on p.v.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

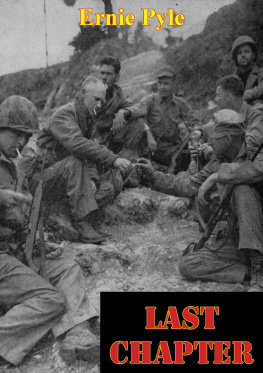

Pyle, Ernie

Brave Men / Ernie Pyle.

p.cm.

ISBN -13: 978-0-8032-8768-6 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-8032-5592-0 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN -13: 978-0-8032-5593-7 (electronic: mobi)

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

G. KURT PIEHLER

Introduction

Few journalists in American history have garnered the fame of World War II war correspondent Ernie Pyle. By 1944 his columns about the lives of American servicemen and servicewomen appeared in more than two hundred daily newspapers and four hundred weeklies. Two wartime compilations of his writings, Here Is Your War and Brave Men , were instant bestsellers. Even before V-J Day Hollywood began a film based on the life of the popular journalist, entitled The Story of G.I. Joe and starring Burgess Meredith as Pyle. On several of Pyles return trips to the States, celebrities flocked to meet him; the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, invited him to afternoon tea at the White House.

Among his peers Pyles work gained widespread respect, especially among the small fraternity of American journalists who covered the European Theater of Operations. In 1944 Time magazine carried his face on its cover, and that same year he won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting. Reviewers praised Pyles wartime anthologies for their ability to convey the essence of a typical soldiers life. He was the GIs Boswell, and his emphasis on the personal, human side of war was widely imitated by other journalists. Newspapers often declared that they had their own Ernie Pyle reporter on staff.

Pyle also won the respect of the GIs he covered. Only Bill Mauldin, the GI cartoonist who created the characters Willie and Joe, approached Pyles standing among those who served on the front lines. Whenever Pyle visited a unit, people flocked to meet him and share their stories. Senior officers were eager to see Pyle travel with their units because it bolstered morale. In 1943 Stars and Stripes , a paper staffed by GIs, asked Pyle, a civilian reporter, to serve as a guest columnist.

What made Ernie Pyle such a success? How and where had he learned his craft? Born in 1900 in Dana, Indiana, he was the only child of William and Maria Taylor Pyle, who owned a small farm outside of town. In his adolescence Pyle yearned to escape his small Midwestern town, seeking opportunity and adventure. When the United States entered the First World War, seventeen-year-old Pyle chafed at the fact that he was not old enough to enlist. In October 1918 he finally could join a Naval Reserve unit for the final months of the war. Disappointed at not serving, Pyle remained in the reserves for several years and even took part in a training cruise on the Great Lakes during the summer of 1921.

In the fall of 1919 Pyle enrolled at Indiana University, and he began taking courses in journalism his sophomore year. Quiet and well liked by his classmates, the young Hoosier wrote for the school newspaper and served a stint as the editor of the summer edition. During the spring of 1922 he and several friends accompanied the Indiana basketball team on a trip to Japan, paying their way by working as cabin boys on a passenger ship. Unable to land in Japan with the team because they lacked proper papers, Pyle and his friends went on to Shanghai and Manila before returning home.

Leaving Indiana University one semester before completing his degree, Pyle began work as a reporter for the LaPorte (Ind.) Herald in 1923. Several months later he secured a position in the nations capital with the recently established Washington Daily News , serving first as a reporter and then as a copyeditor. As a tabloid, the Daily News relied on wire services for national and international news, so Pyles stories focused on local news. Pyles early career would be erratic; he took several extended leaves, weeks or months at a time, often to travel.

In 1925 Pyle married Geraldine Siebolds, an unconventional woman originally from Hastings, Minnesota, who came to Washington during the First World War to work as a clerk for the federal government. She shared Pyles wanderlust. In 1926 they embarked on a cross-country trip by car, touring until they ran out of money. In the end, the couple moved to New York City, and Pyle worked briefly for two major dailies.

In December 1927 Pyle returned to the Washington Daily News , where he served as telegraph editor and, more significantly, in his spare time wrote a regular aviation column, beginning in March 1928. In these columns Pyle began to display what became his hallmark style of reporting: a focus not on producing fast-breaking stories but rather on developing a deep, descriptive style that captured the flavor of life and individuals. Aviation in the interwar years was glamorous, adventurous, and dangerous, and Pyle became friends with James Doolittle, Amelia Earhart, Ira Eaker, and a host of other prominent members of the aviation community in the nations capital.

In 1932 Pyle became managing editor of the Daily News and was forced, with much reluctance, to abandon his aviation column. Although fearing his career had reached a dead end, Pyle, one biographer has maintained, honed his abilities as a writer through his work as a copyeditor and managing editor. He filled in as a roving columnist in 1935, and this assignment became a permanent one with the Scripps Howard newspaper chain. As such, until Pyle went off to war in 1942, he and his wife traveled all forty-eight states, Alaska, Hawaii, the Panama Canal Zone, and several Latin American countries gathering stories. Although Pyle interviewed his share of celebrities, his pieces focused primarily on average Americans in communities across the United States. He interviewed professionals, blue-collar workers, politicians, farmers, and small-town merchants. Pyle gained a steady readership, but efforts to syndicate his pieces nationally met only limited success.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Pyle sought an overseas assignment in part to escape his troubled marriage, troubles exacerbated by his wifes mental illness and alcoholism. In 1940 he arrived in London in time to cover the Blitz, the Nazi bombing campaign against Britain, and he focused his columns on the heroism of individual Londoners. In late 1941, as Japanese-American relations deteriorated, he wanted to embark on a tour of the Pacific. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declaration of war he vacillated, wanting to resume his column, enlist in the army, or serve as a civilian war correspondent. Granted a draft deferment, he covered the deployment of the first U.S. units to the United Kingdom in 1942. Not until his arrival with the U.S. troops in the invasion of North Africa in late 1942 did Pyles previously solid but unremarkable career soar, as he acquired an immense following for his wartime columns.

Why did Pyle acquire such a following? What does his style of reporting say about the nature of the Second World War? Pyle did not belong to the fraternity of war correspondents who reveled in the dangers and glories of war. He lacked the flamboyance or literary talents of an Ernest Hemingway. In contrast to William Shirer, A. J. Liebling, or Edward R. Murrow, Pyle in his reporting seldom focused on epic events, great leaders, or grand strategy. Rather, he filled his columns with accounts of the dedication, bravery, and courage of particular privates, sergeants, and junior officers. He also dwelt on the mundane and the routine. Pyle described how soldiers lived and how an infantryman seldom got a hot meal or a shower when at the front. He described the importance of mail to a soldiers morale and what music GIs liked. He reported on the snippets of conversations he had with servicemen and servicewomen or what he had overheard.