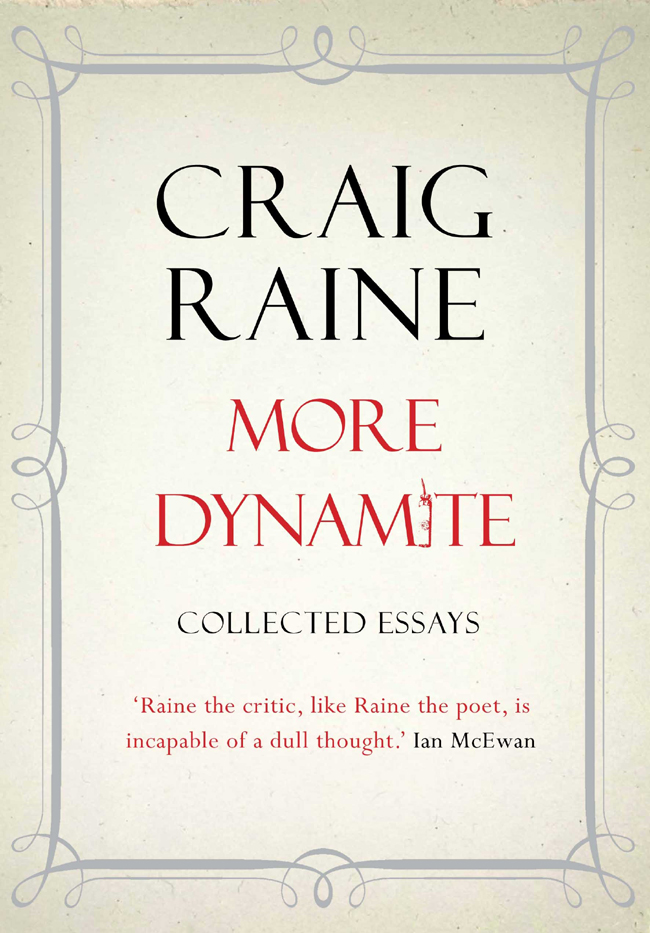

MORE

DYNAMITE

Also by Craig Raine

The Divine Comedy

How Snow Falls

Heartbreak

The Onion, Memory

A Martian Sends a Postcard Home

Rich

History: The Home Movie

Clay: Whereabouts Unknown

la recherche du temps perdu

Haydn and the Valve Trumpet

In Defence of T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot: Image, Text and Context

Collected Poems, 19781999

1953

The Electrification of the Soviet Union

A Free Translation

A Journey to Greece

Change

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Craig Raine, 2013

The moral right of Craig Raine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The author is grateful to the following publications in which the essays of this book originally appeared, sometimes in slightly different form: Aret, the Times Literary Supplement, the Kipling Journal, the Financial Times, Peter Lang, Penguin Books, the New Statesman, the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, Another Magazine, the London Review of Books, Modern Painters and Memory: An Anthology.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781848872875

E-book ISBN: 9781782392057

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WCIN 3Jz

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Patrick Marber and Debra Gillett

Contents

PART ONE

Books Reading the Fine Print

Isaac Babel

( 2002 )

My wife, Ann Pasternak Slater, met Nadezhda Mandelstam in Moscow in 1971, shortly after the publication of Hope Against Hope. The sequel, Hope Abandoned, was finished and waiting in another room. The poets chain-smoking widow jerked her thumb over her shoulder: More dynamite in there.

Isaac Babel was another dynamitist a writer whose explosive force derives from his terse transcriptions of first-hand experience. He wrote to his friend Paustovsky: on my shield is inscribed the device authenticity. Some paragraphs of his prose are acts of deliberate terror. The simple shock-waves of the actual, the cruel, the irrefutable, are his speciality. His sudden, ruthless, marvellous gift leaves the reader trying too late to look away from what Babel is compelled to show us. There is no escape. The violence is calculated to injure the readers bourgeois sensibility, to destroy his good taste, to trap him in the epicentre of the blast to terrorise him.

Dulgushov is fatally wounded: He was sitting propped up against a tree. He lay with his legs splayed far apart, his boots pointing in opposite directions. Without lowering his eyes from me, he carefully lifted his shirt. His stomach was torn open, his intestines spilling to his knees, and we could see his heart beating (my italics). The narrator lacks the courage to finish him off, as the wounded man asks.

Afonka Bida tells the story of a Cossack whose wounded horse has to be shot. First, he feels in the wound with his copper-coloured fingers, then a comrade shoots the horse: Maslak walked over to the horse, treading daintily on his fat legs, slid his revolver into its ear, and fired (my italics). Deranged with grief, Afonka Bida goes on the rampage and returns with a replacement mount. It has cost him an eye: he had combed his sweat-drenched forelock over his gouged-out eye.

Afonka expresses his sorrow in a phrase Wheres one to find another horse like that? which recalls another story in the collection, Crossing the River Zbrucz. The narrator is billeted on a family of Volhynian Jews in Novograd. He lies back on the ripped eiderdown and dreams restlessly about battle. He is woken by a pregnant Jewish woman tapping him on his face. I quote the rest of the two-page story, about one quarter of the total:

Pan, she says to me, you are shouting in your sleep, and tossing and turning. Ill put your bed in another corner, because you are kicking my papa.

She raises her thin legs and round belly from the floor and pulls the blanket off the sleeping man. An old man is lying there on his back, dead. His gullet has been ripped out, his face hacked in two, and dark blood is clinging to his beard like a lump of lead.

Pan, the Jewess says, shaking out the eiderdown, the Poles were hacking him to death and he kept begging them, Kill me in the backyard so my daughter wont see me die! But they wouldnt inconvenience themselves. He died in this room, thinking of me ... And now I want you to tell me, the woman suddenly said with terrible force, I want you to tell me where one could find another father like my father in all the world!

That sudden terrible force is Babels speciality, too. But it depends not just on the way the mundane nightmare is succeeded by the infinitely worse waking nightmare. It depends also on what follows the dark blood in the beard shaking out the eiderdown. In those four alert words is all the shock, all the tragic incongruity, of ordinary lifes unbearable, bearable continuities.

This is Berestechko and more Jews:

The old man was screeching, and tried to break free. Kudrya from the machine gun detachment grabbed his head and held it wedged under his arm. The Jew fell silent and spread his legs. Kudrya pulled out his dagger with his right hand and carefully slit the old mans throat without spattering himself. He knocked on one of the closed windows.

If anyones interested, he said, they can come get him. Its no problem. (my italics)

You know it is true. No fiction writer would dare this black farce the fastidiousness of the barbarians meticulous barbarity, the etiquette observed by the executioner knocking on the closed window. It is writing with the greatest possible specific gravity. It exerts an awful, irresistible pull on the reader. There are the ingredients for a sick joke here, the shape of perverse laughter but Babel skirts the absurd and renders it as sober, almost off-hand, factual, unquestionable.

The casual cruelty and the laconic prose recall the italicised prefatory micro-bulletins above the stories in Hemingways In Our Time. Quoted like this, the Babel stories satisfy the imperatives set down in his diary: short chapters saturated with content; very simple, a factual account