To Laura

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

A day before the course of his presidency was forever changed, Ronald Reagan walked to church with his wife, Nancy. Sunday, March 29, 1981, was bright and warm, and as the Reagans strolled through the White House gates and across Pennsylvania Avenue, the president held the first ladys hand. Trailed by Secret Service agents and a few journalists, the couple waved at onlookers and smiled for camera-toting tourists. As they walked through Lafayette Square, a woman pushed her young child through the security perimeter. Grinning, the president bent over to say hello.

Lately Reagan had not been able to attend church as often as he would have liked. During the previous years campaign it had been hard enough; since the inauguration, it had been almost impossible. For obvious reasons, security requirements for any trip outside the White House were cumbersome. He also didnt want to impose on parishioners, who had to be screened by Secret Service agents and were often distracted by the presence of the president and his wife.

But that spring morning, the Reagans had chosen to attend the eleven oclock service at St. Johns Church, a place of worship as intimately connected to American history as any in the nation. The Episcopal church, just off the north side of Lafayette Square, was designed by the same architect who rebuilt the White House and the Capitol after they were damaged in the War of 1812. Its half-ton steeple bell had been cast by Paul Reveres son; a piece of stained glass donated by President Chester A. Arthur in memory of his wife hung in its south transept. Nicknamed the Church of the Presidents, St. Johns now welcomed the nations fortieth president, a man who revered both God and country.

The rector, the Reverend John C. Harper, had preached to every president since Lyndon B. Johnson. On this Sunday, the Reverend Harper delivered a sermon about faith and about finding Gods handiwork in ordinary things. He told a story about a sculptor who hammered and chiseled a large block of marble into a statue of Christ. When the sculptor was done, a young boy who had watched him at work asked, Sir, tell me, how did you know there was a man in the marble?

Harper then made the message of his parable plain. People have often asked that question of Christians who have seen God in Jesus Christ, in a stone statue, in a stained-glass window, in some human life, he said. How did you know He was there?

The answer, Harper said, was faith.

Before and after Harpers sermon, the Naval Academy choir sang several hymns, which the president found inspiring. Later, writing in his diary, Reagan commented that the midshipmen looked & sounded so right that you have to feel good about our country.

Just before noon, the Reagans returned to the White House, this time traveling in an armored limousine. They ate lunch, spent a bit of time rearranging the furniture in the Oval Office, and then retired to the residence.

Only two months into his tenure, Reaganlike every presidenthad an ambitious political and legislative agenda. But the next day, according to his schedule, would not be especially arduous. The only event of note was a trip to a downtown hotel for a twenty-minute speech to a trade union.

* * *

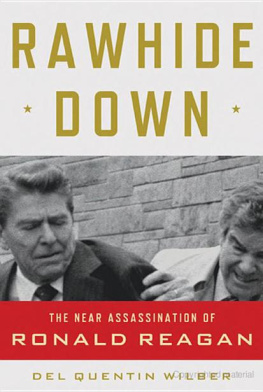

T HE BROAD OUTLINES of what happened the following day are well known. The president had just finished giving his speech when he was shot by a deranged gunman. He was rushed to a hospital and underwent surgery; by that evening, it was almost certain that he would live. In the hours and days after the shooting, Reagans aides worked assiduously to assure the country that the presidents life was never in real danger and that he would soon recover. Indeed, Reagan returned to the White House just twelve days after the assassination attempt and gave a stirring speech to Congress less than a month after leaving the hospital.

But much of what happened on March 30, 1981, was not revealed; most especially, the White House kept secret the fact that the president came very close to dying. Over the years, a number of details about that terrifying day have emerged, but only nowafter many new interviews with participants and an extensive review of unreleased reports, closely held tape recordings, and private diariescan the full story be told.

What is also clearer in retrospect is how crucial this moment was to Reagans ultimate success. Before that day in 1981, the country had suffered through two difficult decades. No president since Eisenhower had served two full terms: Kennedy was slain; Johnson declined to seek a second full term after the debacle in Vietnam; Nixon was forced to resign in the wake of Watergate; Carter served just four years after becoming identified with the countrys malaise. During the 1980 election, the nation was haunted by the Iranian hostage crisis, which spoke to deep-seated fears that the United States might be ungovernable or perhaps in irrecoverable decline. Partly out of frustration with politics as usual, voters turned to a former movie star who seemed to promise a fresh approach, even if he was sixty-nine years old when he took the oath of office.

Reagan had not gotten off to a strong start. In the two months following his inauguration, he was relentlessly criticized by Democrats for not caring about the poor, for proposing steep cuts in federal programs, and for sending military advisors to El Salvador, which, some felt, might become another Vietnam. By mid-March, he had the lowest approval rating of any modern president at a similar point in his term: during what should have been his postinauguration honeymoon, only 59 percent of Americans thought he was doing a good job. His commanding victory the previous November seemed all but forgotten, and White House officials and pollsters were preparing for more difficult days ahead.

All that changed on March 30. The news of the shooting stunned the country: teachers wheeled televisions into classrooms, praying citizens filled churches and synagogues, lawmakers darted into back rooms for updates on the presidents condition. Only eighteen years after the assassination of President Kennedy, the United States once again teetered on the brink of tragedy. Instead, the nation witnessed triumph. A team of Secret Service agents saved Reagans life at the scene of the shooting; in the hours that followed, a team of surgeons and nurses saved the presidents life a second time.

The real hero of the day, though, was Reagan himself. In the most unscripted moment of his eight highly choreographed years in office, he gave the American people an indelible image of his character. In severe pain, he insisted on walking into the hospital under his own power. Throughout the medical ordeal that followed, he never lost his courage or his humor. The attempt on his life occurred just seventy days into his term, but more than any other incident during his years in the White House, it revealed Reagans superb temperament, his extraordinary ability to project the qualities of a true leader, and his remarkable grace under pressure.

* * *

A S THE PRESIDENTIAL limousine raced to the hospital on that terrible Monday in March, the Secret Service agents attending Reagan remained calm and methodical. Even in all the chaos, they never broke protocol by using the presidents name when speaking over their radios. Instead, they referred to him by his code name, Rawhide. They used other code names as well: the limousine was Stagecoach; the command post at the White House was Horsepower; Nancy Reagan was Rainbow. At a time when radio traffic wasnt scrambled and anyone with a police scanner could eavesdrop on the movements of the president, the codes were an essential precaution.