Table of Contents

Guide

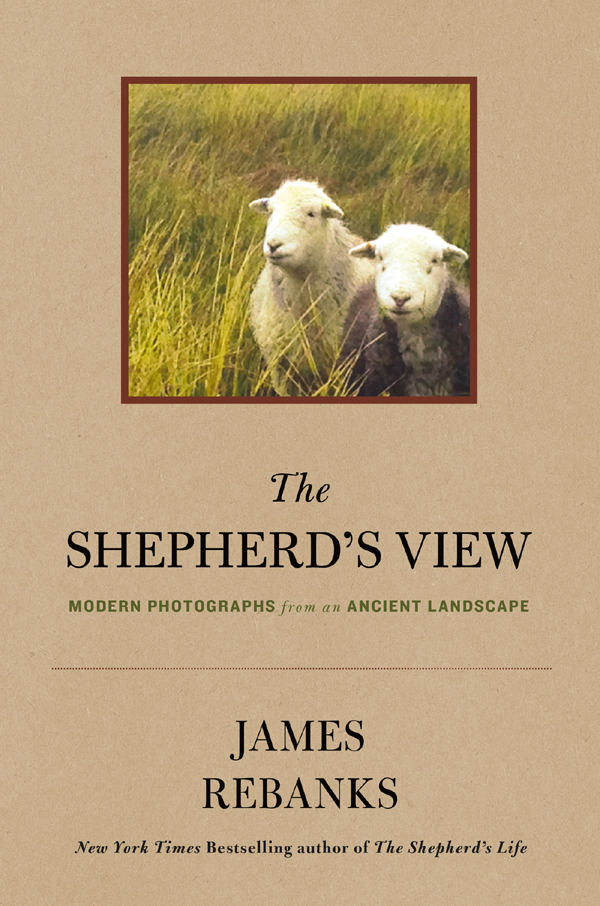

The

SHEPHERDS

VIEW

Modern Photographs from an Ancient Landscape

JAMES REBANKS

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

ALSO BY JAMES REBANKS

The Shepherds Life:

Modern Dispatches from an Ancient Landscape

For the men and women who make this landscape what it is.

I am the luckiest man alive, because I get to live and work in the most beautiful place on earth: Matterdale in the English Lake District.

When I was a child we didnt really go anywhere, except for a week on the Isle of Man when I was about ten years old, and I never left Britain until I was twenty.

Even now, years later, the best bit of any travelling is coming home.

I live and work in the English Lake District, a tiny little chunk of Northwest England just beneath the Scottish border. It doesnt have the biggest mountains in the world, or the largest lakes, or the most spectacular waterfalls, or even the most amazing creatures, and it isnt very wild.

But it is one of the most important landscapes on earth, and it became important by an accident of history.

Until the mid-eighteenth century, ours was a surprisingly difficult place to get to. You had to pass over mountains or moorland, or even over the sands of an estuary between tides. So an older way of life survived here, protected by poverty and isolation.

Then, with the growing prosperity of Britain as a trading and industrial nation, new roads in were built, and the old clashed with the new. Suddenly this place became a battleground between the forces of change in the name of progress and other voices that said its valleys, lakes, and small farms should be conserved and protected from industry and development. The world had gotten smaller, and our lands were now just an hour or two north by carriage, and later by train or car, from the birthplace of the industrial revolution, Lancashire. It could all have been swept away, but it wasnt.

Writers, artists, and thinkers flooded into our landscape and found in it a counterpoint to everything that worried them about the emerging modern world and what William Blake called its dark satanic mills.

For the first time people formulated arguments for conservation, for a public interest in protecting endangered placesarguments that are now familiar to everyone around the world.

The Lake District became over time the most written-about landscape in English literature. Most influential amongst these writers were the poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, but many others came, too. They defined what we think of as beautiful in nature and craft around the world, promoting an eye-pleasing combination of the natural and manmade. A generation or two before that, mountains were thought to be menacing and ugly, but suddenly fashions changed and mountain valleys with pretty lakes were all the rage.

Wordsworth summed up what many of these artists felt when he wrote that this landscape was a sort of national property in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy.

Those were radical, world-changing words in 1810, the first published call anywhere for something like a national park.

He also described the region as a perfect republic of shepherds, a place where aristocratic elites had little power over the working people who had secured legal tenure to their land. The people working on the land and shaping it were deemed to matter.

A generation later, other wealthy individuals bought many of the small farms to protect them from change and development. Most famously, Beatrix Potter invested the proceeds from her bestselling childrens books about Peter Rabbit and his friends in this way.

Potter and other benefactors left these farms and their hefted flocks of fell sheep (hefted means sheep being tied to a part of the mountain or moorland by a sense of belonging taught by their mothers, despite the mountains being unfenced common land) to the National Trust to be protected and sustained for the good of the nation.

So this is a national park, but not the kind that an American might recognize. Unlike Yellowstone or Yosemite, it isnt a wilderness, and it doesnt belong to the government. It has instead a complicated and messy English tapestry of ownership.

The National Trust is a charity that protects some things in our landscapes or towns. It doesnt own all or even most of the land, just some small special bits within it. Farming families, like us, own other bits of it and are its stewards.

It is a national park because it is a landscape molded by being farmed, because it inspired important ideas about nature, and because it was one of the birthplaces of the worldwide conservation movement.

The thirteen valleys of the Lake District cover just 885 square miles, and contain more than two hundred fells, sixteen lakes, and countless tarns (think a pond on a mountain). It is home to more than forty thousand people, and every inch of its protected landscape tells a story about how people have lived in it for ten thousand years (and farmed it for five thousand). Today sixteen million people a year visit the Lake District.

It is also the largest area of common land in Western Europe, a unique preservation of a way of farming once experienced everywhere, until land was enclosed and put under the ownership of individuals, for their sole use, instead of existing for communities. On our common land survives an ancient farming system and breeds of sheep that make it work. All of this survives in the midst of crowded modern Britain and a world in constant flux.

When English people dream of a rural arcadia, they usually dream of our landscape.

My family is simply one of two hundred to three hundred such families who still live and farm this land.

The unique history of this place made for a particular kind of people. The fells and long, wet, cold winters make people here tough and intolerant of nonsense. The people are deeply rooted on their land, and families go back many generations alongside each other. The common land system means we have to work together as shepherds. We have a strong ethical code based on collaboration, honoring other peoples property and rights, and acting decently.

My shepherding life is not unique, but the product of an ancient legacy that still is very much alive. I hope it lives for many generations to come.