TO

DICK

CONTENTS

Guide

I HAVE so many pictures of my dog Ivy that it isnt even funny. Spinning through the mosaic of tiny thumbnail photographs on my computerpast rows of blurry sunset shots, generic-looking streetscapes, and the usual family photosI come across dozens and dozens and dozens of pictures of my dog. Here is Ivy in the garden. Here is Ivy sprawled on the sofa. Here is Ivy chasing a ball, a butterfly, her tail, a Frisbee, a dust mote, the cat. Here she is, in poses worthy of a coat of arms: a Welsh springer spaniel passant gardant on a field of azure. Here are close-ups of Ivys face, shot with a fisheye lens, so that her damp black nose looks like an undiscovered planet. One entire subcategory consists of pictures of Ivy swimming, her ears trailing on the water, leaving slender twin wakes; another is photographs of Ivy in various postures of sleep, looking like a rumpled red-and-white rug. And I have countless studies of Ivy standing on the wall in front of my house, sometimes at daybreak, when she glows with pink light, canis illuminata, or at sunset, when she appears as a springer-spaniel-shaped silhouette against a reddening sky.

The thing is, Ivy is a marvelous subject. She is patient, unselfconscious, and, if I do say so myself, unbelievably attractive. Unlike my son, who either dodges the camera or makes goofy faces to foil my efforts, Ivy holds still, smiles, even vogues. No wonder I fill megabyte after megabyte with images of her. And filling other hard drives and scrapbooks are the dogs of my past: Duffy, my childhood West Highland white terrier, usually photographed barking madly at imaginary enemies; Molly, a leggy, elegant Irish setter, my companion for thirteen years, beginning when I was a junior in college; Cooper, my first Welsh springer, who came into my life around the same time as my iPhone did, which meant I couldand I didtake pictures of him almost every minute of every day.

All of my dogs made such willing, wonderful, irresistible subjects, but the real reason I have so many pictures of them is that none of these photographs quite get it right. They are artifacts, but little more. My pictures of Ivy capture parts of her, moments and glimpses, and some are satisfying portraits, but they never sum her up. Oh, they do a pretty good job informing you of what a Welsh springer spaniel looks like, but theyre missing something fundamental because they dont convey anything of her true presence. Theres nothing of the steady, kindly attention she pays me, or the tenderness of her gaze when Im having a bad day, or the excessive excitement with which she greets me when Ive been gone, say, five minutes. No photograph has ever done justice to her hammy moments, such as the look of abject tragedy she adopts about a half hour before mealtime, sending the message that she has never been fed before, will probably never be fed again, is moments from fainting, might actually have already fainted, and is a very, very, very good dog.

Most of all, what my pictures dont capture is the astonishing quality Ivy and all dogs possess: the power to be deeply present. Even when Ivy is asleep in a room at the other end of the house, she is still noticeably in residence. I can immediately tell if shes out for a walk as opposed to being in another room. The molecules in the house just arrange themselves differently. The stillness is a little heavier when shes not around. When shes not home, I can sense that no ear is tuned to detect the grumble of the mailmans truck approaching or the sound of a squirrel skittering along a tree branch. If Im home alone and shes home, too, I dont need her to be sitting beside me to keep me company; its enough to feel her somewhere nearby.

A house without a dog is a static space. A house with a dog somewhere in it is a house on alert, just moments from bursting into activity, especially if the dog hears the refrigerator open. Anyone who has lived through the death of their dog knows too well the suffocating quiet of a house without one. The first time you come home to the empty house, it aches with hollowness and silence, and the phantom concert of dog noisesthose now-absent tail thumps, nail clicks, and tag jinglesjust about breaks your heart. My millions of dog snapshots dont portray that strange, marvelous experience of coexisting with one of these creatures. Still, I snap away, trying to get it right. I will end up with an epic digital record of my dog, but I know I will never portray what its like to have her as my living, breathing roommate.

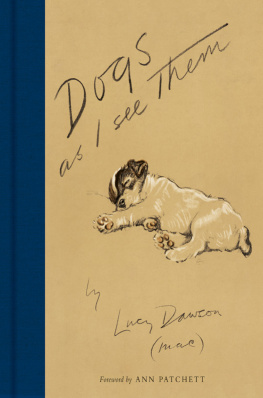

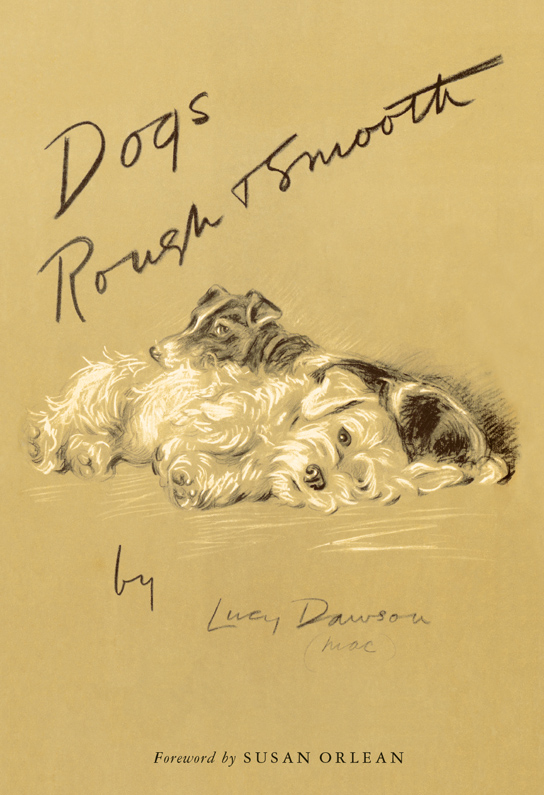

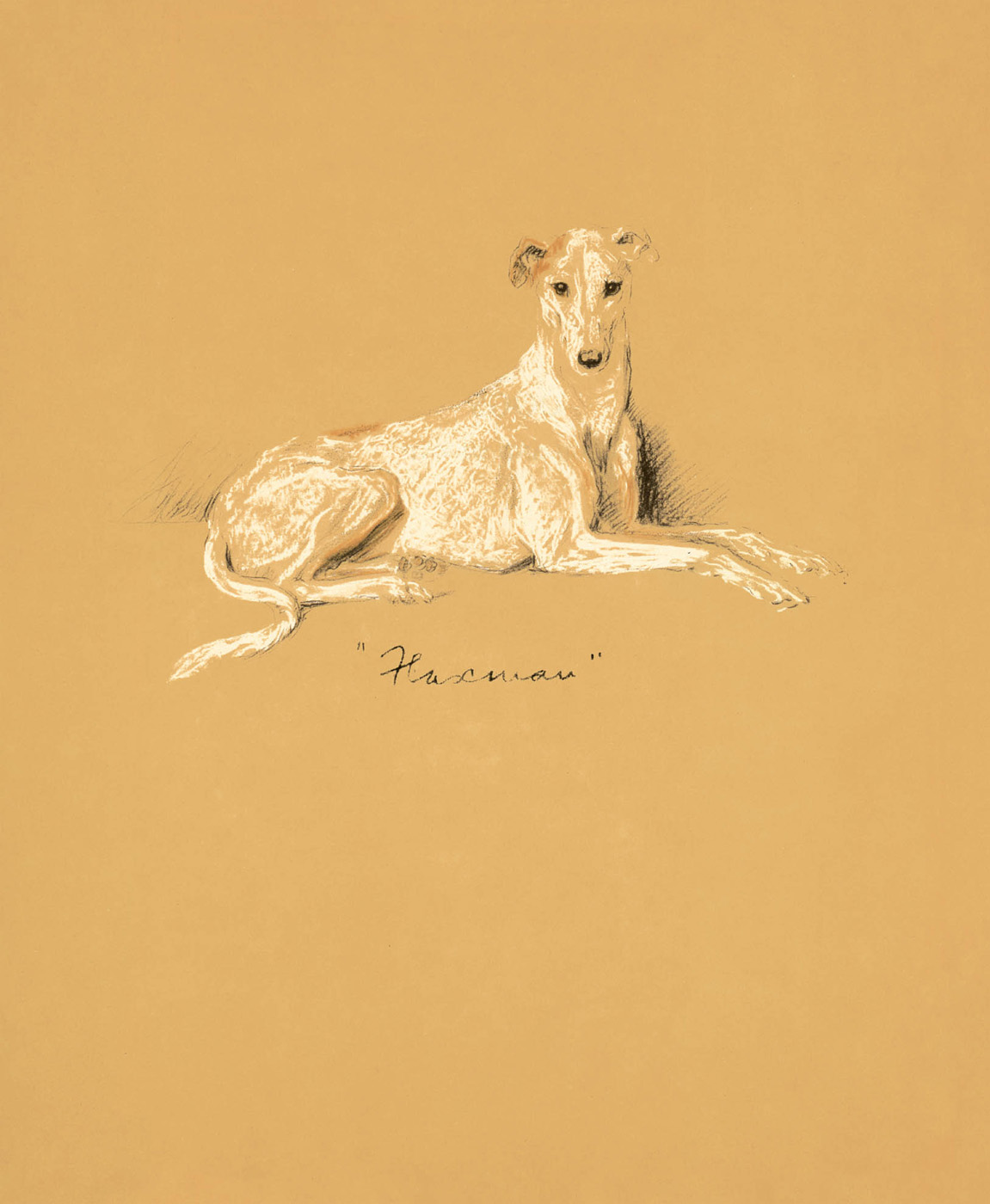

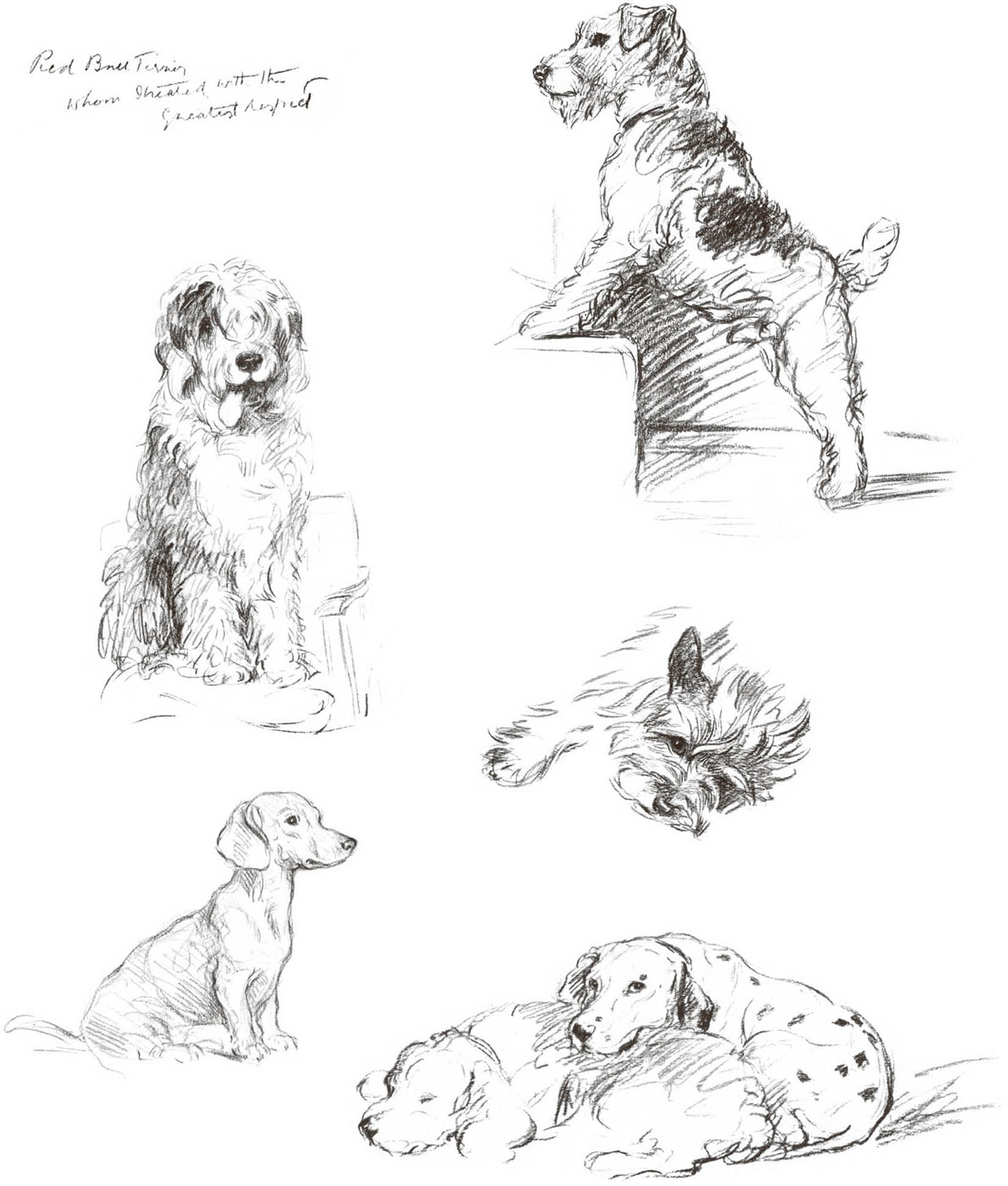

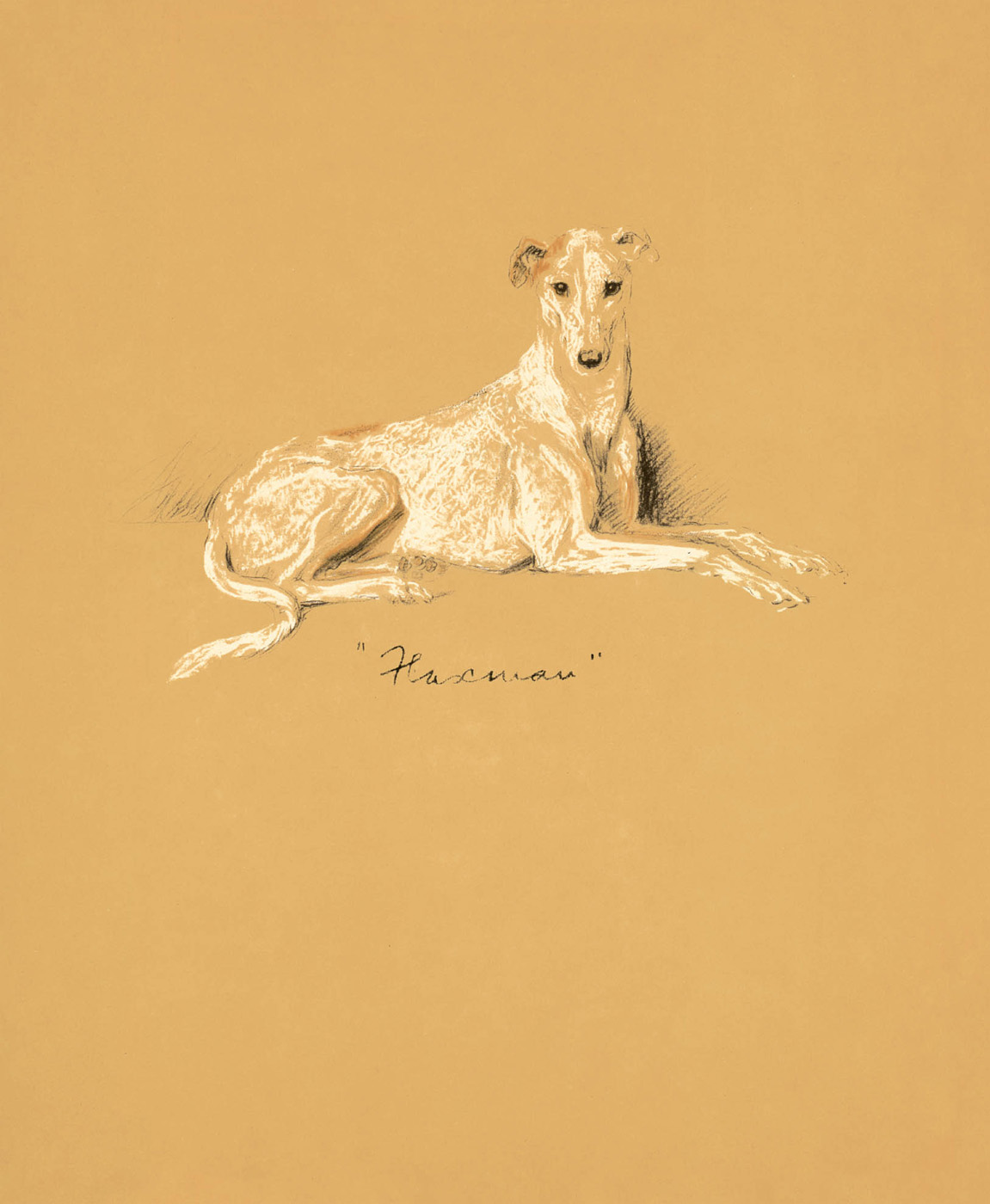

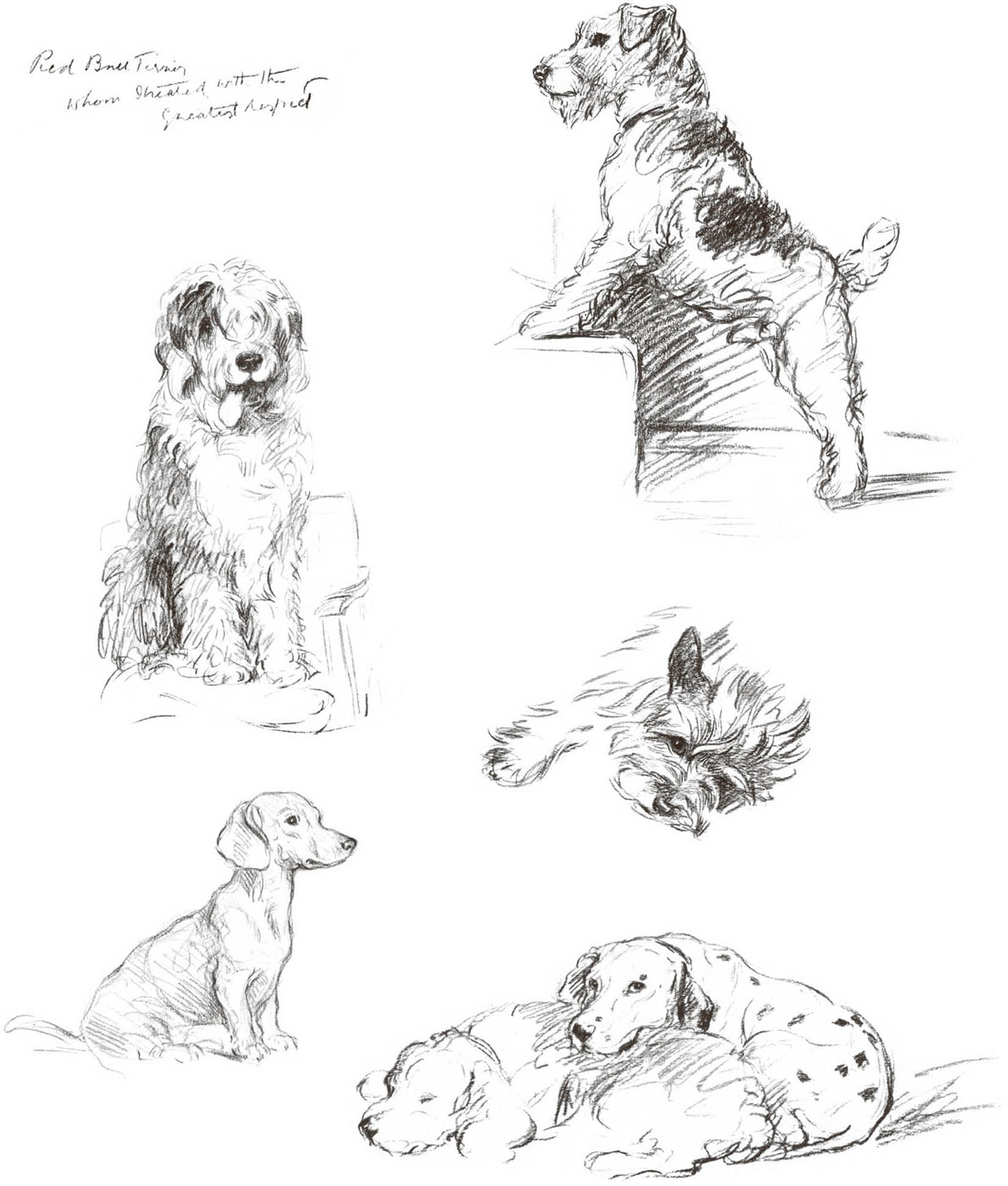

Lucy Dawson, on the other hand, was always getting it right. To start with, she was better than anyone at sketching the fold of a fox terriers ear, or the tender little sag of a spaniels upper lip, or the coursing energy of the muscles beneath a whippets skin. The casualness of her drawings makes them almost seem like throwaways, but its just a trick. Each of her pencil strokes is precise, and the sum total is uncanny in its accuracy. Lucy Dawson was one of many animal portrait artists in England in the early and mid-1900s. At the time, it was customary for aristocrats to have their foxhounds and lapdogs immortalized in a painting, so animal portraiture was something of a boom industry. The style of the period was formal and faux-heroic, and the subjects were usually plopped down against a cluttered chintz-filled backdrop or posed stock-still in an impossibly green Elysian paradise. The results were lovely paintings, brilliantly rendered, but most of the poor dogs ended up looking as animated as taxidermy.

By contrast, Lucy Dawsons drawings are simple. One or two include a hint of a chair or sofa arm or a bowl, but most of her drawings consist of the dog and a scribble of shadow against a depthless plain page. Instead of stiffness and strict composition, her work radiates doggy motion. Lucy Dawsons dogs loll or nap or sit like real dogs, not props. Sometimes they have their tongues dangling and their fur mussed up, or theyre asleep in a pile, like real dogs, which a formal painter would have never allowed. Some of her subjects are even facing away from her, preoccupiedthat is, looking for snacks. Bunch, busy (terribly), Dawson notes below her portrait of Bunch, a plump white Sealyham, whose nose is buried in her food dish, investigating whether a crumb might have been overlooked at dinner.

Which brings me to another pleasure in getting to know Lucy Dawsons work: in addition to being a crackerjack artist, she was a hilarious, sharp writer. Her brief commentaries accompanying each portrait are like your favorite aunts droll asides muttered under her breath at a family dinner. Taffy, the wire-haired terrier, who is a little stout, was persuaded to sit still only by being tempted with sweeties, but I hope he does not often indulge in that diet. About Snoodle, the dachshund: I did not see her again until a few months after her sittingsand how she had lengthened! Bustle, another Sealyham, has a partiality for cigarettes, which have to be hidden, as they are not the most suitable diet for a Sealyham. There is no question that Lucy Dawson loved dogs, but its also quite clear that she found them pretty funny, tooand by implication, we are pretty funny for being so devoted to them.