Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Bonita, who took me there

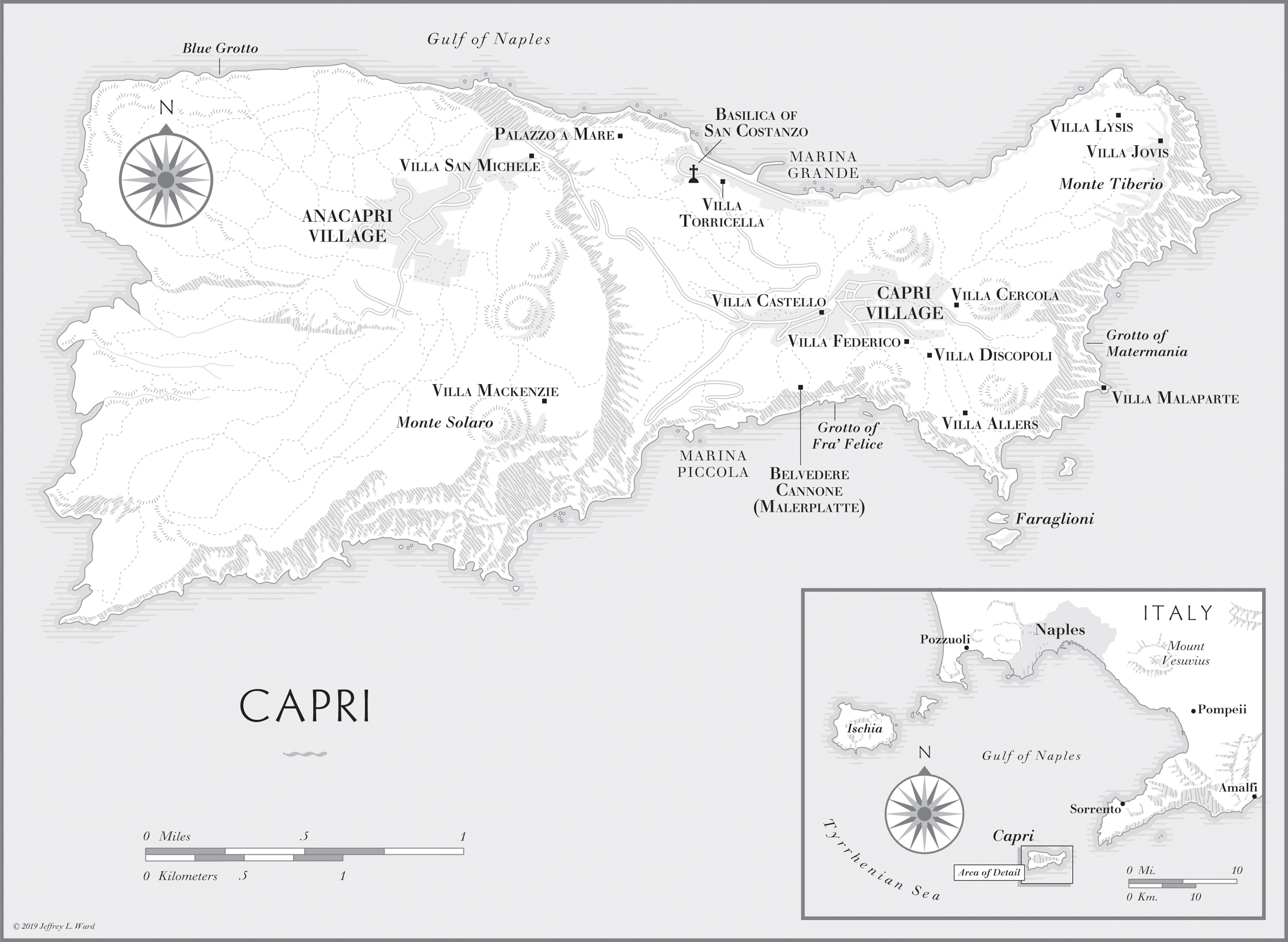

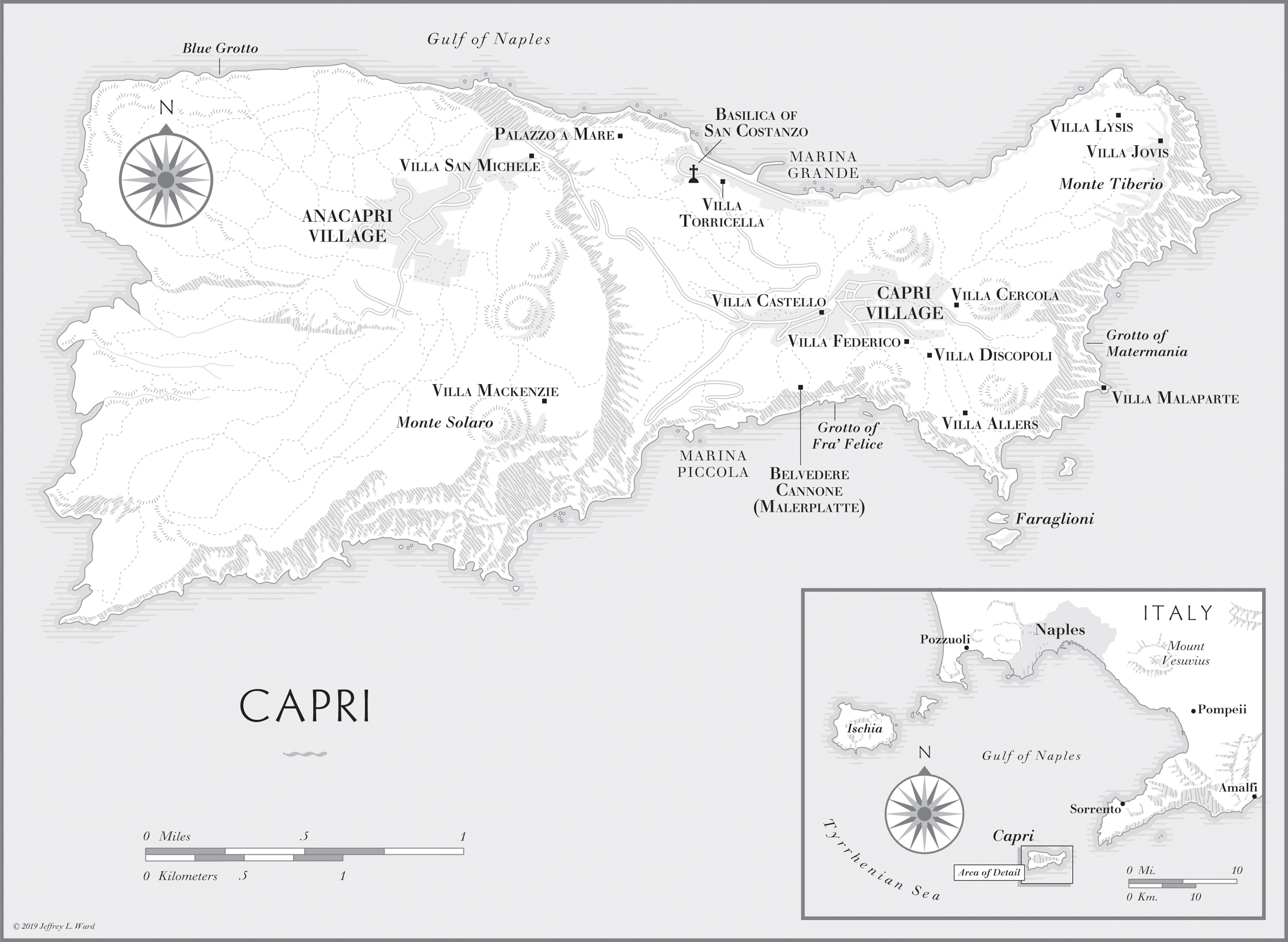

F ROM THE MAINLAND, Capri looks tantalizingly near, peaking up from the sea like a perfect meringue, just out of reach, but it has always been a world apart. The island is just twenty-two nautical miles from Naples, yet until the twentieth century, getting there was an adventure. The Gulf of Naples is often crossed by storms, and high seas are common even in fine weather. The island is girdled by rocky cliffs, with two small coves: the Marina Grande, a ridiculous misnomer, which was barely large enough to accommodate seagoing ships until the Fascists modernized the port in the 1920s, and the Marina Piccola, little more than an anchorage, with no beach to make landfall. Even when steamships were making transatlantic travel routine, a cruise to Capri was scarcely less perilous than it was when Goethe attempted to visit there, in 1787. The poet breathed a sigh of relief when his ship turned away during a terrifying electrical storm, and we left that dangerous rocky island behind us.

The main reason that Capri managed to remain aloof throughout most of its history was its poverty, extreme even by the standards of southern Italy. The island made a poor prize for invaders. Its stony, precipitous terrain was unsuitable for agriculture apart from lemons, which grew in prodigious plenty on the mainland, and grapes, but Capriote wine was notoriously bad. The island had little to offer except lovely views, admired by everyone who came to visit but worthless until the twentieth century, when the boom of mass tourism made the island rich.

On historical maps, Capri turns from pink to blue to purple, to represent it as a territory claimed by whatever empire was holding dominion over Naples, always the islands true liege. Greeks, then Romans, the Byzantine and the Ottoman Empires, Napoleon and the Bourbons, swapped the island around like a bad banknote. By comparison with the architectural heritage of the mainland, Capris imperial overlords left scanty remains, with the spectacular exception of the emperor Tiberius, who ruled the Roman Empire from Capri during the last years of his reign. He built a vast palace atop the islands highest cliff, but little of it has survived except brick arches and ramparts. The tiny municipal museum in Capri village just manages to fill two rooms, and the most interesting objects there are fossils. With the unification of Italy in the nineteenth century, Capri became a part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy, but in name only. Setting aside the omnipresent Neapolitans, mainland Italians were only slightly less exotic in Capri than the foreign visitors.

Capris most valuable asset is intangible: its robust life as a symbol. Like any good symbol, it can be taken in many ways, but the island most often serves as an emblem of freedom. Since antiquity, Capri has been a hedonistic dreamland, a place where the rules do not apply: a Mediterranean prototype of Las Vegas. Twenty-two miles proved to be just far enough to liberate the island from the canting religious morality of Europe and the stern laws that came with it. For many of the artists who sought refuge there, Capri was still under the imperishable influence of its first foreign occupants, the Greeks: a relic of archaic Hellas, before the rise of the polis, with its demands on the citizen, where the individual lived in harmony with nature, saturated in sunlight between sky and sea. The promise of personal freedom brought with it a fantasy of pleasure without limit. In plain words, like Las Vegas, Capri got a reputation as a place where easy sex of every variety was available in abundance and not unduly fraught with consequences.

Capri did not give rise to a culture of its own: Las Vegas was built by gangsters, and Capris isolated situation made it a favorite haunt of pirates and smugglers, also not ordinarily known as patrons of the arts; the island never had a prince. The native population was too small, and paradoxically the island was too close to the mainland to nurture its own artistic traditions. There was never a Capriote style of pottery, no indigenous school of lyrical poetry. Foreign visitors brought their culture with them. In the nineteenth century, as the global economy transformed great swaths of northern Europe into industrial parks and poured smoke into urban skies, writers, artists, and other dreamers voyaged to distant island paradises described by early explorers and exploited in trashy fiction. Tahiti, Bali, and other tropical islands off the main trade routes promised a simple life, free from the material demands of the modern world. Capri radiated a similar primeval glamour and felt exotic, although it was near at hand. It was a place lost in time: even by the 1920s, telegrams and telephones were rare, and donkeys were the principal mode of transport.

The pursuit of freedom and pleasure that flourished in Capri was not entirely in service to the senses; it brought with it an alluring promise of unloosing creative powers. For an enchanted interlude that began in the Romantic era and lasted until the chaotic years after the Second World War, Capri was a haven for an international community of artists and writers, where anything was acceptable except the commonplace. The simplicity of life on the island made it dirt cheap, always an attraction for artists. German poets went there to write Greek poetry, American painters to paint French paintings, French writers to write English novels, and Russians to plot world revolution. The islands history as a global nexus of artistic creativity may not be apparent to the millions of contemporary tourists who come for the views and the shopping, but it is an integral part of the islands fabric. Even visitors who know nothing about Capris cultural history can feel the genius of the place. It is in the air, waiting to be discovered.

Norman Douglas, the British novelist and travel writer resident in Capri throughout the first half of the twentieth century, captured the intoxicating atmosphere of freedom that emanates from Capris pagan past, and its power to inspire the imagination, in his novel South Wind. Douglass mouthpiece, an antiquarian swindler, attempts to lure a visiting Anglican bishop from the straitened paths of righteousness. As they bask in the glow of a summer sunset, sitting on a terrace high above the Gulf of Naples, he declares that in Capri the sage surrenders his intelligence and grows young again. He recaptures the spirit of his boyish dreams. He peers into worlds unknown. See! Adventure and discovery are lurking on every side. These painted clouds with their floating banners and citadels, yonder mysterious headlands that creep into the landscape at this hour, those islets emerging, like flakes of bronze, out of the sunset-glowall the wonder of