T HE M IRACULOUS F EVER -T REE

Malaria, medicine and the cure that changed the world

Fiammetta Rocco

For Dan, for the best of gifts and so much else besides

And for my father who, without quinine,

would have died as a boy

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Tree of Fevers

Cinchona revolutionised the art of medicine as profoundly as gunpowder had the art of war.

BERNARDO RAMAZZINI, physician to the Duke of Modena, Opera omnia, medica et physica (1717)

Francesco Tortis Tree of Fevers may be nearly three hundred years old, but it swells on the page as though it rose from the ground this very spring. At the crown, its trunk branches like an earthly anemone, and its arms grow thick and dark. On the left side of the engraving, the tree bark hums with sap and leaves grow at intervals in thick bunches of green. The branches on the right, by contrast, are denuded and leafless. Tissue-white, they curl upwards as if in supplication to the Almighty.

Torti, who once saved his own life by taking a dose of powdered Peruvian quinine bark to cure an intermittent fever, as malaria was once called, believed that there were two kinds of fever: those, represented by the leafy branches on the left side of his tree, that respond to treatment with the bark; and those, like the dead willowy kind, that do not.

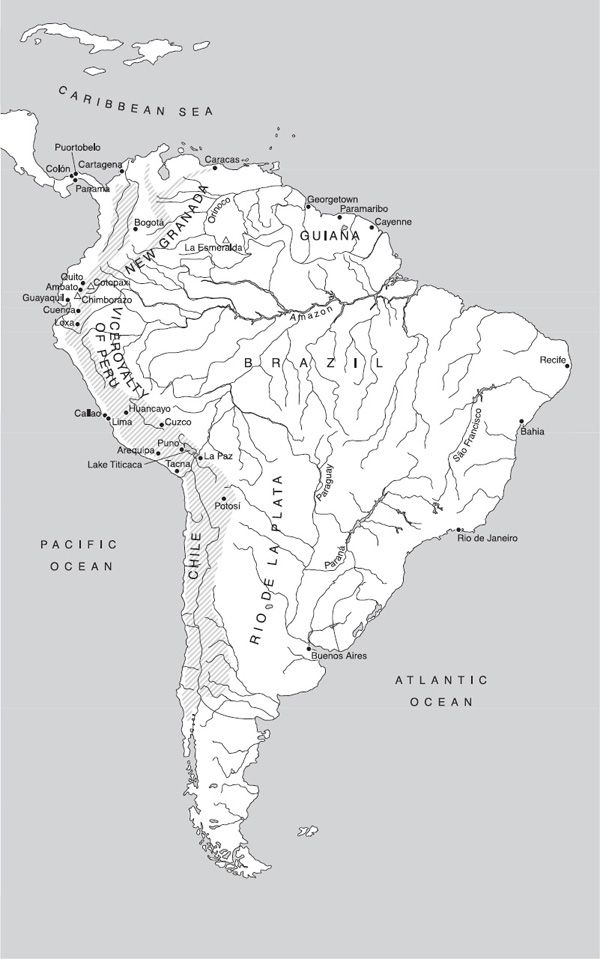

But Torti took his inspiration from another tree, one that he had never seen, and one that for centuries would remain an enigma. The magnificent Cinchona calisaya, the red-barked Andean tree that produces quinine, is one of ninety varieties of cinchona, a relative of the madder family, which also includes coffee and gardenias. Some cinchonas have large leaves, some small; some smooth, some roughly corrugated. But the leaves on the older trees of the true red bark the cascarilla roja that grows eighty feet high are fiery red. The colour offsets the lilac-like flowers that grow in delicate white clusters, and which are followed by a dry fruit that splits, at the onset of winter, to release narrow winged seeds so tiny and fine that they run to as many as 100,000 to the ounce. Joseph de Jussieu, the first European to set eyes on the cinchona, thirty years after Tortis engraving of 1712, believed that Cinchona calisaya was the most beautiful tree he had ever seen.

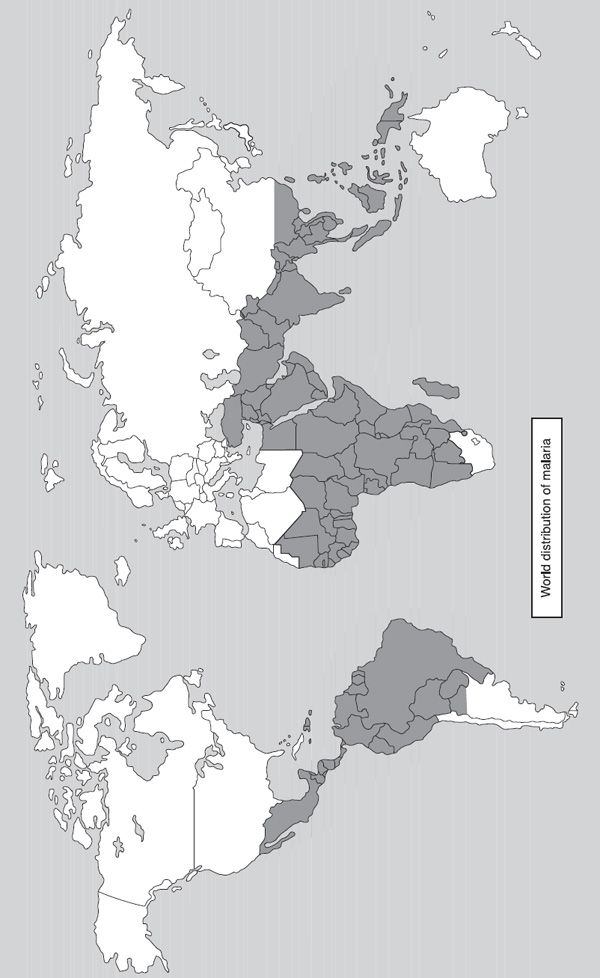

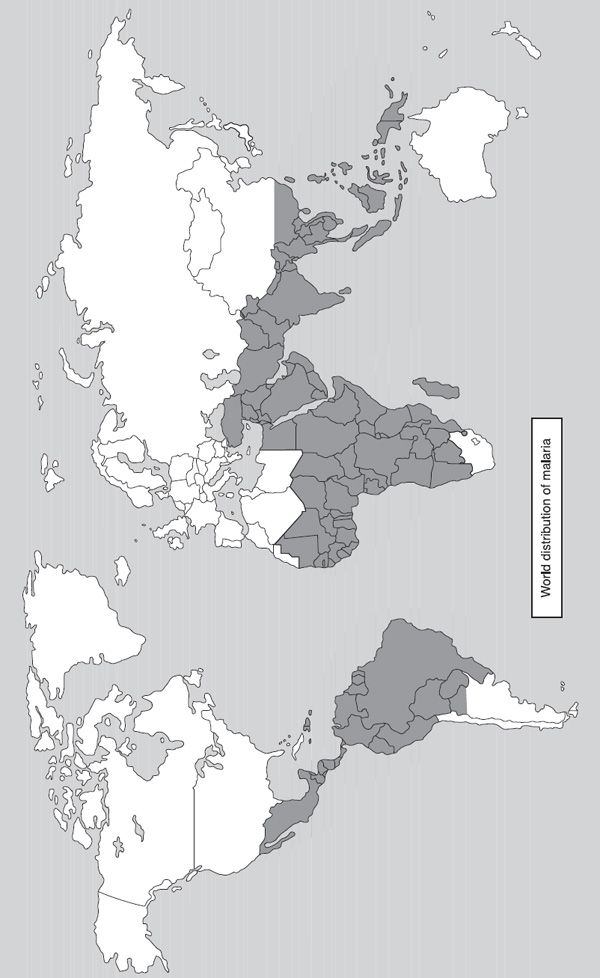

For Torti and de Jussieu, intermittent fever or malaria was a disease of the Old World. No one knew for certain where it came from or what caused it. But everywhere the Old World expanded its boundaries pushed ever on by commerce, religion and war malaria followed. And the price it exacted was beyond imagining. Malarial fever, wrote Sir Ronald Ross, the Englishman who in 1902 was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for proving that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes, is important not only because of the misery it inflicts upon mankind, but also because of the serious opposition it has always given to the march of civilisation No wild deserts, no savage races, no geographical difficulties have proved so inimical to civilisation as this disease.

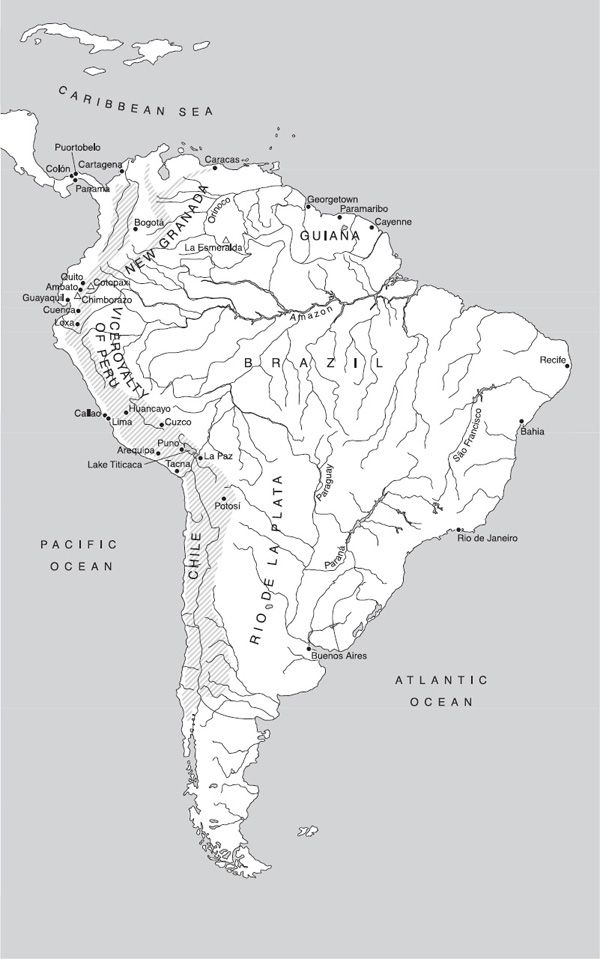

Within the foul-tasting, bitter red bark of the cinchona tree is an alkaloid that prevents and treats malaria. The Peruvian bark, which was first brought to Europe in 1631 or thereabouts, was looked upon as a miracle. But its discovery was also a riddle. Cinchona was a tree of the New World. It grew where the rain was plentiful in the foothills of the high Andes, where malaria had never existed. How did anyone guess that among all the trees in South America, it was the bark of the cinchona that would cure malaria? How was it that a seed so small it is almost invisible could grow into a tree, one eighteenth-century source wrote, that was as crucial to the art of medicine as gunpowder had been to the art of war?

This book is the story of the riddle of quinine, the miraculous fever-tree which transformed medicine and history.

1

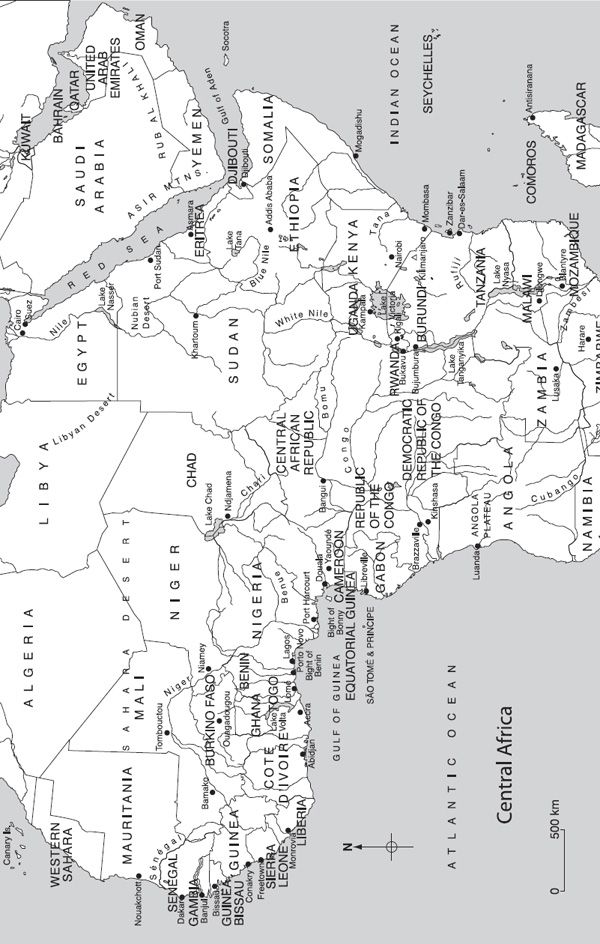

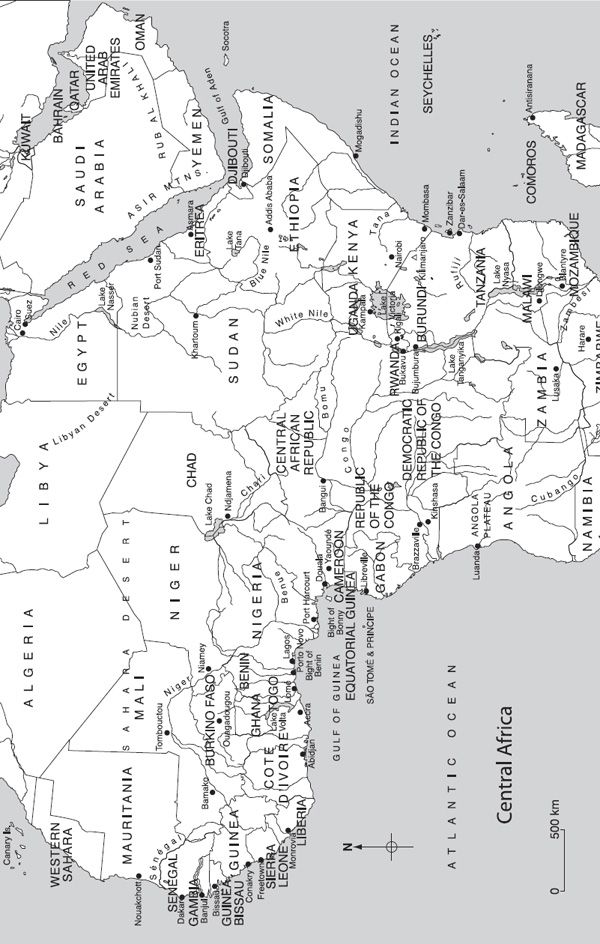

Sickness Prevails Africa

Malaria treatment. This is comprised in three words: quinine, quinine, quinine.

SIR WILLIAM OSLER, Regius Professor of Medicine, Oxford, 190917

If you ever thought that one man was too small to make a difference, try being shut up in a room with a mosquito.

THE DALAI LAMA, 1977

My grandparents had been married for many years when they left Europe for Africa in 1928, though not to each other.

My Parisian grandmother, Giselle Bunau-Varilla, had had at least two husbands, if not three. My Neapolitan grandfather, Mario Rocco, was being sought by Interpol for trying to kidnap his only child. His first wife, a tall, thin Norwegian with wide cheekbones and a finely arched brow, had been labouring for years to expunge him from her life. She wanted, above all, to change their daughters identity from Rosetta Rocco, a Catholic, to Susanna Ibsen, a Protestant and to be rid of her husband forever.

The Neapolitan solution was to remove the child by force and go into hiding, a plan that ultimately failed, though not before it had annoyed the authorities and landed my grandfather in a great deal of trouble.

As an antidote, a year-long safari in the Congo seemed a welcome distraction to all concerned. Yet as the moment of departure drew near, both my grandparents were filled with the excitement of the unknown. Their journey turned from being an all-too welcome respite from their domestic travails to a grand, passionate tropical adventure.

A few hours before New Year 1929, they boarded the sleeper train in Paris that was bound for Marseilles. My grandmother, as always, could be counted on to remain calm even while eloping to Africa with someone elses husband. My grandfather, who had jet-black hair with a deep white streak that swept back from his forehead, only felt his fine sense of the dramatic swell as he put Paris behind him. Dont even tell my in-laws what continent I shall be in, he wrote to his family from the train.

In Marseilles they boarded the SS Usambara, a passenger ship of the Deutsch st Afrika line that would bear them across the Mediterranean to Port Said, through the Suez Canal, and down the East African coast to Mombasa. From there, the plan was to travel by train and on foot across Africas thick equatorial waistline to the heart of the continent. They thought they would be away for at least a year. Longer, perhaps.

My grandparents were accompanied by a sizeable quantity of luggage. To equip themselves for a hunting trip that would take them as far west as the Ituri forest on the banks of the Congo river, they had paid a visit to Brussels, to the emporium of Monsieur Gaston Bennet, a specialist colonial outfitter who sold ready-prepared safari kits with everything a traveller might need for a journey of three, six or even nine months.

Monsieur Bennets inventory sounds much like the necessities that H. Rider Haggards hero Alan Quartermain packed when he set off in search of King Solomons Mines. For their extra-long hunting trip, he sold my grandparents four heavy-calibre rifles, including a double-barrelled Gibbs .500 which my grandfather Mario, with manly Neapolitan excitement, described in his diary as