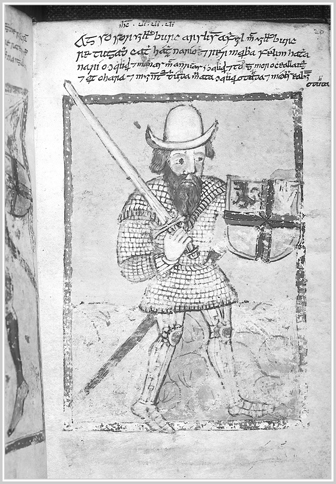

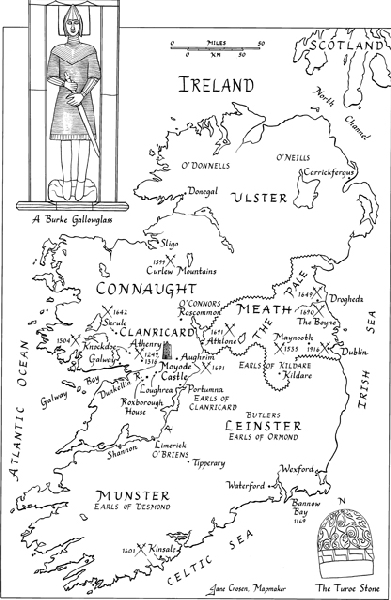

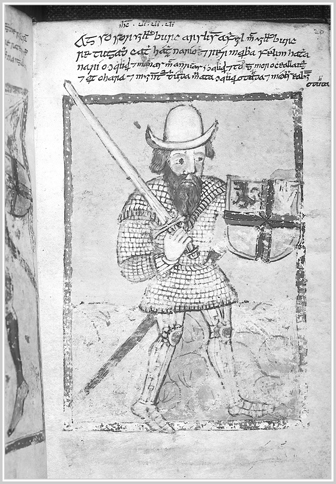

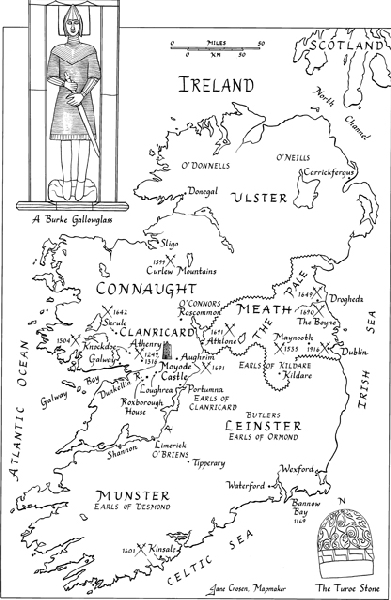

William de Burgo, the grey

Also by James Charles Roy

The Road Wet, the Wind Close: Celtic Ireland (1986)

Islands of Storm (1991)

with James L. Pethica, To the Land of the Free from this Island of Slaves:

Henry Stratford Persses Letters from Galway to America,18211832 (1996)

The Vanished Kingdom: Travels Through the History of Prussia (1999)

THE

FIELDS

OF

ATHENRY

A Journey Through Ireland

JAMES CHARLES ROY

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright 2001 by Westview Press, A Member of the Perseus Books Group

Published in 2001 in the United States of America by Westview Press, 5500 Central Avenue, Boulder, Colorado 80301-2877, and in the United Kingdom by Westview Press, 12 Hids Copse Road, Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9JJ

Find us on the World Wide Web at www.westviewpress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roy, James Charles, 1945

The fields of athenry : A journey through Irish history / by James Charles Roy.

p. cm.

ISBN-10 0-8133-3860-3

ISBN-13 978-0-8133-3860-6

eBook ISBN: 9780786742547

1. IrelandSocial life and customs20th century. 2. Roy, James Charles, 1945 . Homes and hauntsIreland. 3. CastlesConservation and restorationIreland. 4. IrelandCivilization20th century. 5. IrelandHistory. I. Title.

DA959.1 .R69 2001

941.5082dc21

00-048473

Design by Heather Hutchison

THE FIELDS OF ATHENRY

This book is dedicated to the memories of

Penelope Preston

Gormanston Castle

County Meath

Sans Tache

&

Robert Brown

Ballyportry Castle

County Clare

There were yielded out of Connaught violent men,keenness, great deeds.

Irish, c. A.D. 700

Ireland and Connaught

INTRODUCTION

He smelleth the battle afar off, the

thunder of the captains and the shouting.

A friend of mine once asked me, Why Ireland? He had just returned from two weeks of misery in the Emerald Isle: atrocious weather, abominable food, expensive drink, and historical remains whose shabby, unkempt, diminutive personality had betrayed all the praise lavished upon them by myself and others. The next time I want to see the sun, Im going to Spain. For a good meal and a glass of wine, to France. And for something extravagant, Rome. They say the Colosseum is quite a sight.

There is little doubt that Ireland is different from other European countries. A peripheral kind of placea pimple on the chin of the world, according to an ancient clericit has never been at the crossroads of life, is always off to the edge. In modern times the country has lagged behind the Continent both materially and culturally, only now losing that sheen of innocence so long its special preserve. Outsiders such as myself lament this transformation, much to the annoyance of progressive Irish friends. You people who have everything never want to share, Ive often been told over argumentative pints of Guinness. You come over for the melancholy Ireland of songs and ballads, the donkey cart and leprechaun. The last thing you want to see here are fast cars or people using computers.

This book records, on two separate levels, my own loss of innocence regarding Ireland. I initiated this experience, unwittingly, in 1969 by purchasing the ruins of Moyode Castle, located on the great eastern plain of County Galway in the province of Connaught. For over fifteen years, the aura of that desolated sixteenth-century shell infected all my thinking, mostly superficial, on Ireland and its extravagant history. I wallowed in all the great blarney of saints and scholars, Wild Geese and rebels, the terrible beauty and Celtic Twilights of William Butler Yeats. When I began working on Moyode in the middle 1980s, these perceptions inevitably changed.

Moyode Castle, 1969

Familiarity breeds contempt runs the old saw, and though my affection for most things Irish remains as strong as ever, the mundane reversals of fortune that plague any substantial building projectand especially those of a Third World nature, as County Galway revealed itself to becan strain the credulity level of any would-be zealot. Shards of Elizabethan prejudice infected my vision: delays, procrastination, financial sleight of hand, interminable tea breaks, the gush of brave talk unbacked by resolution, all caused me to think as a foreigner. Moyode became in many respects more of a burden than a respite.

But familiarity also breeds knowledge. Submerging myself in the details of Moyode Castle and the few immediate acres surrounding it inevitably transformed the obsession I had cherished for so many years. As the scattered physical remnants of this landscape revealed themselves to my wandering eye, as their essentially nondescript and often pedestrian character became apparent, I found myself overwhelmed at just how unglamorous, violent, grubby, and desperate so many details of this history indeed were.

With increasing fascination, moreover, I discovered that just about every phase of the Irish saga had left its physical imprint on Moyode Castle and the fields over which it stood. From the unrecorded blur of pre-Christian Ireland to the Norman invasion of 1169; from the murderous passage of the great de Burgo barons of Connaught to the wild Celtic Burkes into which their line degenerated; from the ravaging Tudor wars to the Confederation of Kilkenney to the fiasco of the Boyne; to the coming of the Protestant Ascendancy to revolt in 1916 and the ensuing Troublesall these events dispersed their generally catastrophic marks on this seemingly bucolic site.

Arnold Toynbee had it all wrong. History is never neat, never concise, never predictable. Generally speaking, it is never fair either. I came to understand, rummaging about the environs of my new home, that Irelands story is a hugely disorganized froth, and that attempts to sanitize the incoherent shambles of its surge through the centuries benefits the countrys major growth industry (tourism) but little else. The personalities, pressures, events, and incongruities of fate all burst our desire for a clean summation of trends and fortunes in what is, I believe, a tragic story and certainly a tragic land. It is easy to bog down in chaos, but no more apt metaphor for the Irish saga is available than in that single word.

The rebuilding of Moyode Castle seemed to me at times a reflection of this lurching narrative that constitutes Irish history, and I record the ups and downs of that experience in this book. I have also attempted to relate Irelands past through what I know happened here in these fields, pastures, ruined buildings, all so amply watered both by sweat and blood. Familiar individuals will enter and leave various scenes in this chronicle, but for the most part the reader will meet characters whom records and annals have tended to ignore. It has been my happy task to bring them, I hope, to life, giving the lie to my friends sarcastic inquiry, Why Ireland? with the rejoinder, Is there anywhere finer?