IRISH FOLK HISTORY

Irish Folk History

TALES FROM THE NORTH

Henry Glassie

Drawings by the Author

Copyright 1982 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed on acid-free paper.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data

Glassie, Henry H.

Irish Folk History.

Texts... selected from Passing the time in Ballymenone : culture and history of an Ulster community, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 1982P.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. TalesNorthern IrelandBallymenone. 3. LegendsNorthern IrelandBallymenone. 4. Ballymenone (Northern Ireland)Social life and customs. 5. Ballymenone (Northern Ireland)History. I. Title.

GR148.B34G55 398.2'09416'13 | 81-43516 |

ISBN 0-8122-1123-5 (paper) | AACR2 |

For the people of Fermanagh

In memory of those who have gone

In celebration of those who remain

CONTENTS

This book is made of the words of the people of County Fermanagh in the southwestern corner of Northern Ireland. Here you will find the history of a small country place as it is told by the people who live there. My first debt is to my teachers in Fermanagh: Bob Armstrong, James Boyle, Johnny Boyle, Michael Boyle, Mr. and Mrs. Gabriel Coyle, Martin Crudden, Mr. and Mrs. Dick Cutler, Ellen Cutler, Mr. and Mrs. John Cutler, John Drumm, Peter and Joseph Flanagan, John Gilleece, Bob Lamb, Mr. and Mrs. Tommy Love, Tommy and Peter Lunny, William Lunny, John Joe Maguire, Owney McBrien, Mr. and Mrs. Paddy McBrien, James McGovern, Rose and Joe Murphy, Hugh Nolan, Mr. and Mrs. John OPrey, Francis OReilly, Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Patrick Owens, Mr. and Mrs. James Owens, James and Annie Owens, Mr. and Mrs. Bobbie Thornton.

The texts in this book were all selected from Passing the Time in Ballymenone: Culture and History of an Ulster Community, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 1982, and I am grateful to the helpful, talented team the Press assembled around my work, to Maurice English, Malcolm Call, Ingalill Hjelm, Dariel Mayer, Peggy Hoover, and especially my friend John McGuigan. Nanette Moloney McGuigan capably braved the endless task of typing.

The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation provided funds for my first stay in Fermanagh in 1972. I was lucky to be named consultant to the Ulster-American Folk Park in County Tyrone, and Eric Montgomery and Bob Oliver arranged subsequent trips for me to Northern Ireland.

Members of my family accompanied me on most of my visits to Fermanagh, and they helped me constantly. For his support and love, I dedicated Passing the Time in Ballymenone to my father. Polly, Harry, and Lydia sat with me and learned. Kathleen Foster not only heard the old stories at the hearth-side, she read my manuscripts, clarified my thought, and brought my life joy.

Help of other kinds was given by Roger Abrahams, Bo Almqvist, Robert Plant Armstrong, Tom Burns, Richard Dorson, E. Estyn Evans, Alan Gailey, Bryan Gallagher, Kenny Goldstein, Dell Hymes, Mary McConnell, Samas Cathin, P. J. OHare, Elliott Oring, Sen Silleabhin, Teresa Pyott, John Szwed, and George Thompson. And no work of mine can pass without acknowledgment of my great teacher, Fred Kniffen. My deepest thanks to them all.

IRISH FOLK HISTORY

PLACE, PAST AND PRESENT

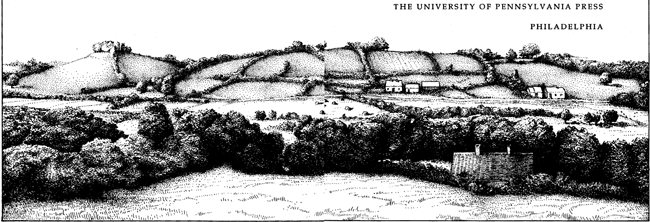

Dark mountains lie along the western horizon, and the land falls, soft and green, rippling over little hills. Atop gentle ridges and around low domes, white houses stand against the wind from the west. Hedges thick with trees cross the upland, colliding and splitting the grassy slopes into meadows and pastures. To the north, the clay hills descend through trim gardens on the moss ground and melt into the brown expanse of the bog. Southward, the land slides along the bottoms to the Arney River running east to Upper Lough Erne. The hills follow, tumbling into the lake, then rising into islands. Around the island-hills of Upper Lough Erne, placid waters shimmer north, widening, narrowing, encircling the compact town of Enniskillen, flowing toward the sea beyond the western mountains.

Here in County Fermanagh, seven miles north and nine miles east of the border breaking Ireland, people pass their days, following the cows over the braes, sweeping their kitchens clean, and wielding spades below, turning the moss ground, stripping the banks of the bog. At last the sky thickens and lowers, night falls, and they walk the deep lanes searching for neighborly hearths, sparks in the dark, places to gather with tea and talk in calm scenes called ceilis. By day and night, people work to build their place on the hills.

Space had been divided and named before their coming, broken into townlands. Each townland centers on the upland and expands, descending to meet its neighbor in the dips between the drumlins. Townland names hint of the past. Drumbargy, they say, means Hill of the Bargains. A fair was held on Drumbargy Brae in days gone by. Rossdoney means Sunday Point. A church once stood by the Arney in the Point of Rossdoney. Sessiagh was the sixth division, the sixth town-land west of Lough Erne, said Michael Boyle, the place of six original settlers, said Hugh Patrick Owens. Townlands give people addresses and identities when traveling, but no single name contains their place. Out of a corner of Rossdoney they have carved Carna Cara, and they have linked Rossdoney with townlands to the north to create an unofficial district called Ballymenone, the Place of the Rivers Mouth, according to the great nineteenth-century scholar, John ODonovan.

Back and forth across the land, people move to connect the hearths on the hills into our district of the country, joining Upper Ballymenone (Rossdoney and Drumbargy) westward along the Arney River through Rossawalla and Ross, Drumane and Gortdonaghy, to Sessiagh. Here they dig and visit, forming and reforming their community.

The skies above them bring too much rain. Gray clouds sail east off the ocean, bursting to drench the soil and wreck the farmers plans. Then the sun cracks the sky, mountains explode on the west, and light dances from field to field, shadowing the hollows, lifting the crouching hills, spattering the green with gleaming homes. Noiseless breezes cross the lake, the waters turn silver, shine, then darken again. Again the winds rise, the rains beat down on the meadows, and farming people learnas they sayto live in all seasons. They drop their plans and endure the bad day, planning anew, looking ahead to the good day, remaining alert, flexible, brave.

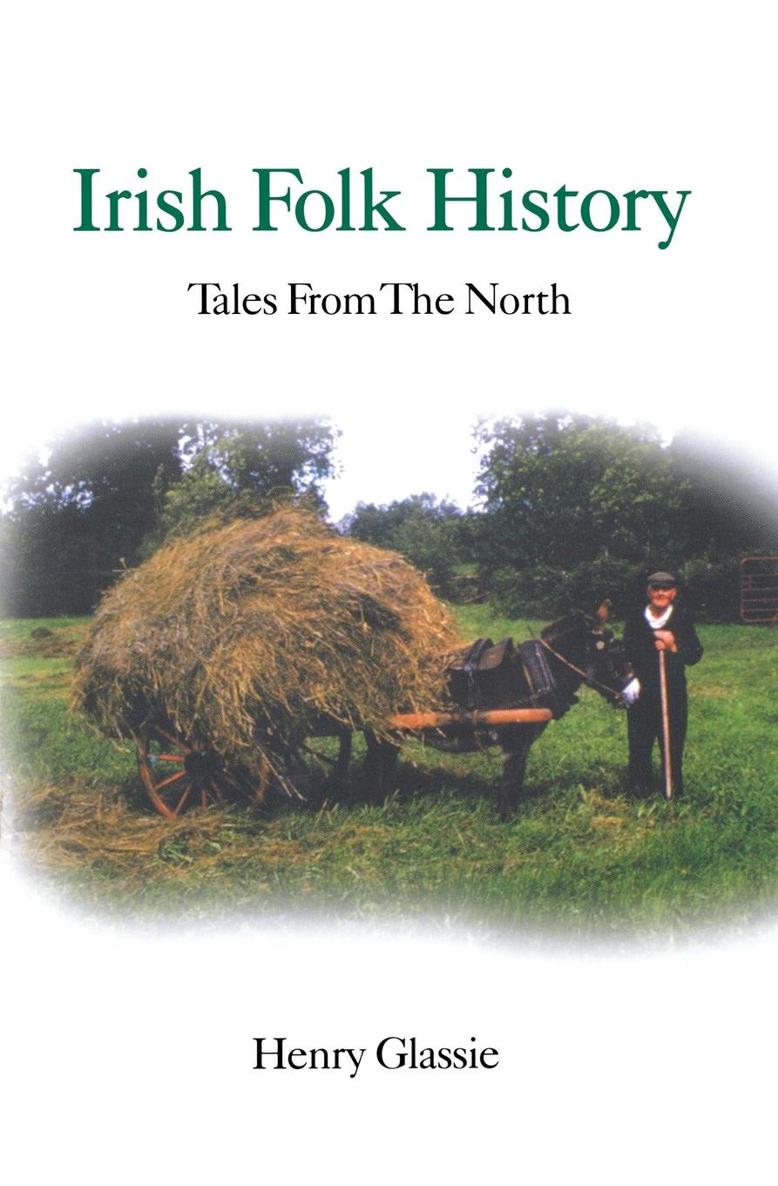

The land carries their cattle. Small farmers rook the lands abundant grasses with pitchforks, winning hay to sustain their cows over the winter. Big farmers, the minority with more than thirty acres and thirty cows, bale the grass or mow it early for silage. But all live off the cows who live off the grass that springs from the clay. Cows make work in every season, on every day, so mens work in the fields, like womens work at the hearth, is continuous, never done.