ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: FOLK MUSIC

Volume 6

COME DAY, GO DAY, GOD SEND SUNDAY

COME DAY, GO DAY, GOD SEND SUNDAY

The songs and life story, told in his own words, of John Maguire, traditional singer and farmer from Co. Fermanagh

Collated by

ROBIN MORTON

First published in 1973 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd

This edition first published in 2016

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1973 Robin Morton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-94398-8 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-66734-8 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-12404-2 (Volume 6) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-64839-2 (Volume 6) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Come Day, Go Day, God Send Sunday

The songs and life story, told in his own words, of John Maguire, traditional singer and farmer from Co. Fermanagh

Collated by

Robin Morton

First published in 1973

by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd,

Broadway House, 6874 Carter Lane,

London EC4V 5EL

Printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd,

London, Fakenham and Reading

Robin Morton 1973

No part of this book may be reproduced in

any form without permission from the

publisher, except for the quotation of brief

passages in criticism

ISBN 0 7100 7634 7

For une paysanne

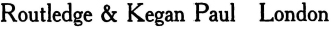

John Maguire feeding his pigs

Contents

John Blacking

Plates

John Maguire feeding his pigs

Experts have for years been warning us that, as a living tradition, the folk music and song of Ireland is fast dying. While not wishing to assist any complacency it must be said that this pessimism simply does not seem to coincide with the facts. The tradition seems alive and well perhaps as a result of well-timed warnings, who knows? Look at the number of good young pipers, fiddlers, flute players, etc.; and there are any number of fine young singers who are experiencing and sharing much delight in the old songs. Perhaps they are changing things a little but then change is of the essence. An unchanging tradition is surely a dead one, and thus of interest only to the antiquarian.

Not only has this revival of interest led the young people to sing and play traditional music, but many of the older generation have taken down forgotten fiddles, or are remembering songs they used to sing. For those who never stopped practising their art there is a new and keen audience wanting to know how it used to be played and sung. The province of Ulster seems to be particularly well endowed with these carriers of the old tunes and songs. This endowment, with a few notable exceptions, has been largely ignored by the scholars and collectors. More recently, however, some have remarked, with ill-concealed amazement, on the strength of the tradition in that province, especially that of song. This is the story of one of the carriers of that song tradition.

I first met John Maguire on a Sunday in late September 1968 and I am now pleased to number him and his wife and family among my friends. However it was because of his reported competence as a singer that I first went to see him in the company of the late Paddy McMahon. It was Paddy, himself a fine, strong singer, who told me about John. So one Sunday afternoon, and armed with a dozen Guinness, we knocked on the door of the cottage at Tonaydrumallard, near Rosslea in Co. Fermanagh. We were ushered into a small, tidy farm kitchen and formal introductions were made. We were lucky to get John there at all, we were told. That day he had just come out of hospital after a car accident, and an injury to his neck was still paining him.

John was sitting on a large leather armchair, in the corner under the American wall-clock, and he looked in obvious discomfort as a result of the accident. I was sure there would be no singing that day but as the afternoon passed we all relaxed and the crack got better. Paddy sang a couple of songs and I held up my end. Then Paddy, always a marvellous catalyst, wondered if John remembered the song about Lough Ooney (see song 24, ). John thought maybe he would if he could just get into the start of it. Well get into the start of it he did and before we left that evening John had given me about twelve songs and an assurance that I would be welcome back any time. I have returned often.

Here is a man who not only has good songs but sings them in a way that shows much of what is best in the Ulster style of traditional singing. In this we do not find the vocal gymnastics of the sean nos singing of the west. The decorations used by John are subtle they have to be listened for, but they are no less effective because of that. The story is all important and nothing is allowed to cloud that. John Maguire is first and foremost a story-teller. His timing is uncanny and the word that springs to mind when attempting to pinpoint the essence of his style is economy.

John Blacking, an ethnomusicologist and Professor of Social Anthropology at Queens University, Belfast, has lent his skills to transcribing Johns singing into musical form. Many thanks are due to him for this invaluable contribution. While the task was no doubt a difficult one, it seems also to have held much fascination. Thus we can look forward to a fuller analysis from Professor Blacking when, freed from the pressure of publication dates, etc., he has had time to work over the material. In the interim he explains his method of transcription in the note on .

Other aspects of the songs, it is hoped, have been dealt with in appendix 4 where it has been attempted to place them within a social and historical context, in so far as that is relevant. The project might have ended there another folk-song collection to add to those already available. However something more has been attempted here.

![Robert Choi - Korean Folk Songs: Stars in the Sky and Dreams in Our Hearts [14 Sing Along Songs with the Downloadable Audio included]](/uploads/posts/book/423508/thumbs/robert-choi-korean-folk-songs-stars-in-the-sky.jpg)