Only fools and fiddlers learn old songs.

Singing costs nowt, Dad used to say. When a mans a-singing he needs no help; when a mans a-cussin, thats when the buggers got trouble.

The first quotation comes from the folk-song collector Alfred Williams, who reported it as an old saying in 1922, and is a cautionary remark that we in folk music generally ignore. The second is from Mont Abbott, born in 1903, in Enstone, Oxfordshire, who learnt most of his songs in the family circle.

Those of us interested in folk songs and music think a great deal of our old songs because we claim that being traditional is what gives them a certain character and cultural value. And, when all is said and done, the whole point of tradition is its connection with the past if something does not have that thread of connection, it cannot be called traditional. So, whether we are interested in the past for its own sake, or in folk song today, we need to understand where it came from.

But 150 years after folk song was first named as a separate musical genre, a hundred years after the great Edwardian collecting boom, and over fifty years after the start of the post-war Folk Revival, we still have a great deal to learn about what made it tick, and, in essence, what made it folk. Which brings us on to the quotation from Mont Abbotts dad.

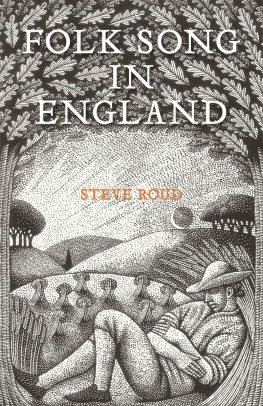

So, this is a book of social history, covering folk song in England from the sixteenth century to about 1950. It is not really concerned with the folk music which developed through the post-war Folk Revival, when everything changed dramatically, nor is it about now, but about what used to be.

Following the trend of recent research, the books main argument is that the social context of traditional singing is the key to understanding its nature, but is also precisely the component which has often been neglected in past discussions of the subject. While individual song-histories are noted in passing, the book is more concerned with who sang what, where, when and how than with the songs themselves.

One of the dominant themes of the book is that folk song, however defined, did not exist in a cultural vacuum, and we will dedicate some time to investigating the other musics that were available to ordinary people in the past, and which potentially influenced the styles and repertoires of their own song cultures.

The book is divided into four parts, with a mixture of chronological and thematic treatments.

The introductory section introduces the field and tackles the vexed question of the definition of folk song, tradition, and other slippery concepts and though it should be said from the start that hard-and-fast definitions cannot be reached in our field, we must still try.

Part One sketches the history of the slow but steady development of interest in the song cultures of ordinary people over the last 250 years or so, which peaked in the remarkable late-Victorian and Edwardian collecting boom. This history must recognise how the collectors own interests and agendas have influenced both the ideas and the assumptions that we have inherited from them, and the nature of the evidence that they have bequeathed to us. This, in turn, will allow us to identify the areas in which this evidence is lacking, and where we need to focus our efforts to plug the gaps in our knowledge.

Part Two presents a chronological account of what we can discover about everyday song practices in each century since 1500, twinned with an investigation into those other musics available at the time. It is the nature of the subject that the later centuries get more than the lions share of our attention.

Writers of general books about folk song usually feel it their duty to give the subject deep roots, but the fact is that there is so little evidence about vernacular singing in the earlier periods that all is speculation, and it is only in the very late eighteenth century that sources become available which allow us to reach reasonably safe conclusions about what ordinary people were up to. The lives of ordinary people are not well documented in general, and what they sang (and how they sang it) is rarely noticed at all.

Each chapter in Part Three focuses on a particular topic, which allows for a more detailed investigation of the song traditions of specific groups of people (sailors and soldiers), particular contexts (at work, in church), or types of song (bawdy or dialect).

The book finishes with two chapters on the mechanics of tradition, which look more closely at how traditional song and music functioned in everyday life, and try to get under the skin of local traditions by addressing topics such as what the singers themselves thought, how they sang, where they learnt their songs, and where they sang them.

*

It will be helpful here to provide a very brief history of the development of folk-song study over the last 150 years, to flag up some of the major concerns which will be addressed in the following chapters.

Between the years 1870 and about 1900, various individuals in England began to notice that certain people, mostly elderly members of the rural labouring classes, had repertoires of song and styles of singing which seemed to operate under different rules, values and standards than either the art (primarily what is now called classical) or the commercial popular music of the day. These individuals called them folk songs, and they were particularly enchanted by the tunes and motivated to start a campaign to collect them and make them known to both the musical establishment and the general public. They quickly became convinced that these tunes were (a) musically very interesting and worthy of preservation; (b) very important because they reflected the very essence of the national musical soul; and (c) fast dying out under the onslaught of such factors as universal education, urbanisation and commercial popular music.

![Robert Choi - Korean Folk Songs: Stars in the Sky and Dreams in Our Hearts [14 Sing Along Songs with the Downloadable Audio included]](/uploads/posts/book/423508/thumbs/robert-choi-korean-folk-songs-stars-in-the-sky.jpg)