THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright1994 by Stacy Schiff

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York.

Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

A portion of this work was originally published in slightly different form in The New York Times Book Review, May 30, 1993.

Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published and unpublished material may be found on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schiff, Stacy.

Saint-Exupry: a biography / by Stacy Schiff.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79839-8

1. Saint-Exupry, Antoine de, 19001944Biography.

2. Authors, French20th centuryBiography. 3. Air pilotsFranceBiography.

I. Title.

PQ2637.A274Z829 1994

848.91209dc20

[B] 944011

v3.1

This book was written for Marc de La Bruyre

Contents

~

Introduction

~

T he predicament of his birth is summed up by one encyclopedia in two words, impoverished aristocrat: Antoine de Saint-Exupry began his professional life as a truck salesman. By 1929 he had distinguished himself as a pilot and published a first novel. Before another five years had passed he was unemployed, living hand-to-mouth. In 1939 he won both the American Bookseller Associations National Book Award and the Acadmie Franaises Grand Prix du Roman for Wind, Sand and Stars; he seemed well on his way to a chair at the Acadmie Franaise. Five years later his politicsmore accurately his lack thereofmade him so much a persona non grata that he lived in disgrace in Algiers, heartbroken and excommunicated, his books censored. That year he became the most famous French writer to go down as a casualty of World War II. He was forty-four years old.

Saint-Exupry did not so much live fast as die early. Our fascination with him has grown as a result, as it does with all things that end before their time, from the Titanic to Marilyn Monroe. The mystery surrounding his deathso neatly presaged in The Little Prince, whose hero witnesses forty-four sunsetshas further enhanced the myth. To it have been added the eulogies: Saint-Exuprys generation comes to an end only today, when he has been dead for fifty years. Survived by a great number of eloquent friends he has been flattened under the collective weight of their half century of praise. That avalanche has naturally provoked a second one: those who have labored to remind us that Saint-Exupry was a man, not a god, have delighted in doing so vitriolically. The detractors have done no more than the keepers of the cult to reveal Saint-Exupry himself; they have tangled only with the legend, of which the writer is now twice the victim.

Under it all is buried one man, by no means ordinary, but not extraordinary either for the reasons we have come to believe. A pilot of indisputable audacity, Saint-Exupry was anything but a disciplined flyer. He flew the mails only briefly, less than six years in all. He played a role in the pioneering age of aviation without having been one of its illustrious practitioners; he was more the Boswell of the early days. Relatedly, he was not much dedicated to routine. He displayed a stunning lack of personal ambition, and was a resolute nonjoiner. Disobedience was often to his mind the better part of valor. His friendships were solid but composed of equal parts loyalty and squabbling. His sentimental history is a thorny one. At the same time Saint-Exupry was a man of tremendous, towering personality, of certain genius. Little of it crept into the tempest-tossed life, however; only a portion crept into the work. He was perhaps at the height of his powers recounting the tale of his near-death by thirst in the Libyan desert at the dinner table, over which his enchanted listeners plainly slumped with sympathetic dehydration. No one who met him ever forgot him.

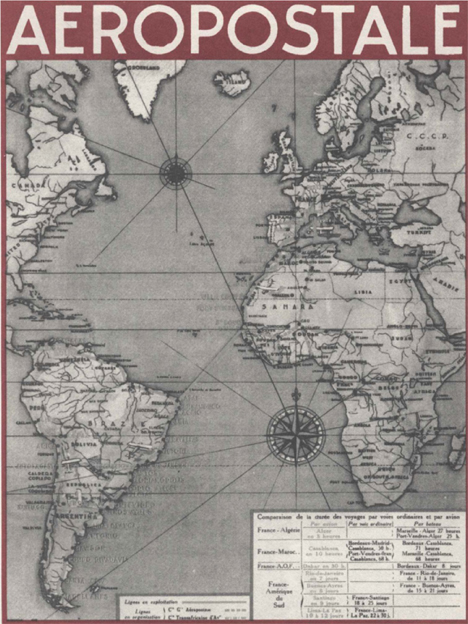

How could an aviator write, or how could an aviator write as lyrically as did Saint-Exupry? And how did an aristocrat come to fly as a mail pilot? There was nothing predetermined about either career, and the worlds of letters and aviation were further apartespecially in France in the 1920sthan a man with a foot in each realm might have liked. Generally speaking the two are not professions that go well together. The writer lives with some detachment from experience, which it is his task to recast; a pilot works his trade with a fierce immediacy, perfect presence. One may reshape events, the other must nimbly accommodate them. For Saint-Exupry the two careersand with them the life and the oeuvrewere inextricably bound. His biographer enjoys no greater advantage. Most of his work is journalism, romanticized, but still autobiographical; what is not journalism pure and simple is easily enough decoded. The pages hold little fiction, limited fantasy, a vast sea of fact. And while Saint-Exupry could be absentmindedsix years into his marriage he could not remember his wedding datehe neither reinvented nor muddied the past. He was not untruthful. He put a gloss on things, but he lived, too, for that gloss, for a quixotism that would be his undoing. The fashion in which he shaped the events he faithfully reported ultimately tells us as much about him as do the events themselves. It makes it possible to begin to imagine the truly critical hours of his life, those he spent alone at several thousand feet, moments no biographer can touch.

While the works are true to the lifethe authors mind wanders on the page just as it did in the cockpit; a common literary construction for Saint-Exupry is over A I was thinking of Bthey do not entirely stand in for the man. They are simple; Saint-Exupry was not. The anguished writer of petulant, indignant, downtrodden letters is nowhere to be found in the early books. Here, too, the myths have taken their toll: Saint-Exuprys biographer commits to addressing the provenance of the Little Prince, that disarming visitor from Asteroid B612, and yet to date the chroniclers of his life have pretended that the man who wrote some of the most tender pages of our time had no private life, only a morass of a marriage. It is not easy to understand the Little Prince if one holds too much to the caped crusader of lore; it is at the same time too easy to write off Saint-Exupry altogether if one takes him only at his written word. It is a richer life than he let on, poorer as it was in all the transcendent qualities that make the literature soar, so much more earthbound than it appears to have been.

A note on the name, which is pronounced Sant-Exoopairee, with all syllables accented equally: famous men famously change their names. Saint-Exupry admitted he had un beau nom and was enough attached to it that he forbade two women who shared itan elder sister and his wifefrom publishing under it. (Both ultimately defied him.) Friends and acquaintances were to take liberties even where he did not: after a childhood of nicknames, he was transformed by others into Saint-Ex, who became the pilot of legend. He himself made only one concession on this front. When the writer settled in New York after the fall of France he authorized his American publisher to insert a hyphen into his name, so as to discourage those who insisted as addressing him as Mr. Exupry. I have retained the late-arriving hyphen here; to do otherwise in English leaves an odd impression. Is he one of the saints of France? a confused son of Charles Lindbergh asked his mother in 1940. Laughingly Anne Morrow Lindberghwho had fallen under the Frenchmans spell the previous yearreplied that he was indeed, if not in the usual sense of the word.