THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

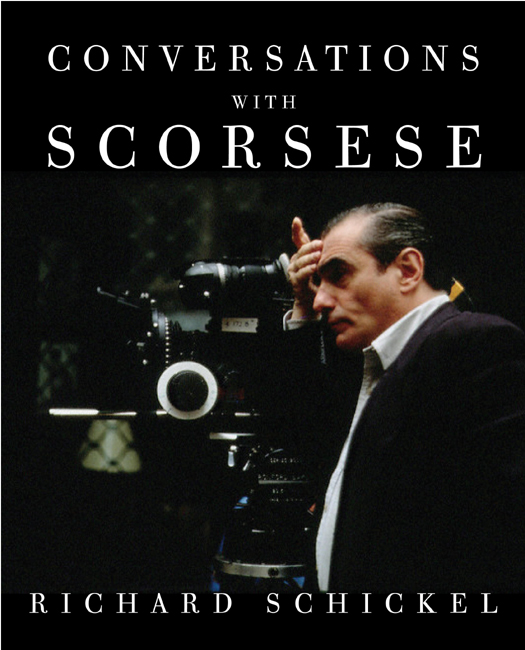

Copyright 2011, 2013 by Richard Schickel

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Photograph of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker in the editing room of Goodfellas used with permission of David Leonard.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scorsese, Martin.

Conversations with Scorsese / Richard Schickel [interviewer]. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Includes filmography.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-307-59546-1

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-307-38879-7

1. Scorsese, MartinInterviews. 2. Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesInterviews. I. Schickel, Richard. II. Title.

PN 1998.3. S 39 A 3 2011

791.430233092dc22 2010034250

Cover image Bureau L.A. Collection / Corbis

Cover design by Chip Kidd

Published March 10, 2011

First Paperback Edition, January 13, 2013

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

We are an odd couple, Marty and I. I grew up in a placid suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, cosseted by my middle-class familyloving, indulgent, always avoiding openly expressed emotions. Im certain that I gravitated to the movies because I was looking for melodramatic excitement, a relief from the niceness that was the highest value of that time and place. Martys young years were, of course, the opposite, spent mainly in Little Italy on New Yorks Lower East Sideworking class, but also criminal class, with the Mafia providing much of the neighborhoods half-hidden social organization and control. There was an element of danger onwell, yes, all rightthe Mean Streets of his boyhood. And there was an element of anxiety in his home, which was rife with discussions of complex family issues tensely, if lovingly, argued out. He was escaping a vastly different sort of reality when he went to the moviesmelodrama and fantasy, to be sure, but of a kind that was actually less threatening than the harsh realities this asthmatic little boy encountered in his daily life.

Weve more than once laughed about this: he envies the peace of my picket-fence childhood; I would have loved the stir and occasional menace of Little Italy. But it speaks to the appeal of the medium in the 1940s and even the 1950s, when the movies were thought to be dying, that members of our youthful demographic almost universally went to themtheir sheen and shimmer were that irresistible. The difference between Marty and me and the rest of our friends is that they drifted away from the movies, except as a form of casual entertainment, while we almost helplessly professionalized our passion. That process, as Marty experienced it, is what much of this book is about. In talking with him Ive often felt we are like immigrants from two different countries meeting on neutral ground and discovering that we can communicate in a third language: the language of film.

It helps, of course, that in addition to being a filmmaker Marty is a passionate film scholar, a man who devotes almost as much time to studying and preserving the movie past as he does to making new films. This is a matter that naturally concerns me as a critic and film historian. It may also help that I eventually, much more modestly, became a filmmaker myself, a documentarian specializing in movie history. Technically, as well as historically and aesthetically, we communicate easily, instinctively, in the shorthand of shared experiences.

That was not always the case. We met for the first time in 1973, when I was working on the first television programs I wrote and directed, a series of interviews with American movie directors of the classic age. I was running their pictures of an evening at my apartment and I casually asked Jay Cocks, at the time my reviewing colleague at Time magazine, if hed like to take a look at Howard Hawkss His Girl Friday some night. This was well before the home video revolution, when you had to haul out a cumbersome 16mm projector to see movies in your living rooma bigger, rarer deal than it is now in the digital age. Anyway, Jay was, and is, one of Martys oldest friends, dating back to their days at the New York University film school, as well as his occasional screenwriting collaborator, and he asked if he could bring Marty along, which he did. I cant recall anything memorable being said. We all just had a merry time rewatching one of the greatest of all romantic comedies.

No friendship arose out of that encounterlargely, I think, because I was, at the time, not particularly fond of a lot of Martys films. I did not, for example, greatly care for Mean Streets. It was Martys breakthrough film, and though I have since come to respect it, I still dont quite love it. I enjoyed the lightsome Alice Doesnt Live Here Anymore, but had to wrestle hard with Taxi Driver, before giving it the good review it deserved. I remember Henry Grunwald, Times great managing editor, scribbling this note on the proof of my piece: You dont like this movie as much as you say you do. He was right at that moment, though he would be wrong now.

A little later, Marty and I shared one of the most awkward moments of my career. This was in 1977 when the producer of Martys New York, New York, Irwin Winkler, set up an early screening of the film for me. It was, you may recall, a drama with music about the troubled relationship between a bandleader (Robert De Niro) and his vocalist (Liza Minnelli)in part, a tribute to the kind of musical comedies MGM had made in the 1940s and 50s, in part a dark and painful romance. These two ideas never really meshed, and the production had also been attended by all sorts of troubles, personal and professional, that rather obviously afflicted the finished product. Irwin invited Marty and me to dinner after the screeningat which I found I couldnt say a word about the film that would not have hurt Martys feelings. So we awkwardly talked around the only subject that was of interest to either of us. I didnt know at the time that Marty, Irwin, and almost every one else connected with the film had the gravest doubts about it, and were perhaps hoping against hope that an objective observer might see something more promising in it than they did. Nor did I know that Marty was on the verge of a life-threatening illness, the result of exhaustion and the interaction of a wide variety of drugsprescription and, shall we say, nonprescriptionhe had been taking to keep himself going through a brutal schedule.

Somehow, Marty survivedmany of his friends insist that it was quite a near thingand when he was recuperating in the hospital De Niro visited him to insist that he at last focus his attention on a project on which the actor had invested a profound passion: Raging Bull. Marty had always been dubious about the film, if only because he had never had the slightest interest in boxing (or any other kind of sports). De Niro, however, thought boxing was just a pretext for the film and judged that Marty, having now touched bottom in his own life, might forge an emotional connection with this story about the boxer Jake LaMotta reaching a similar condition. De Niro was obviously, spectacularly, right, and