Table of Contents

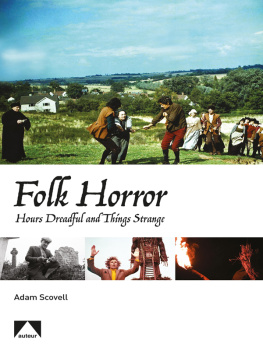

Folk Horror

Folk Horror

Hours Dreadful And Things Strange

Adam Scovell

First published in 2017 by

Auteur

24 Hartwell Crescent, Leighton Buzzard LU7 1NP

www.auteur.co.uk

E-ISBN 978-1-911-32524-6

Copyright Auteur Publishing 2017

Designed and set by Kim Lankshear

Printed and bound in the UK

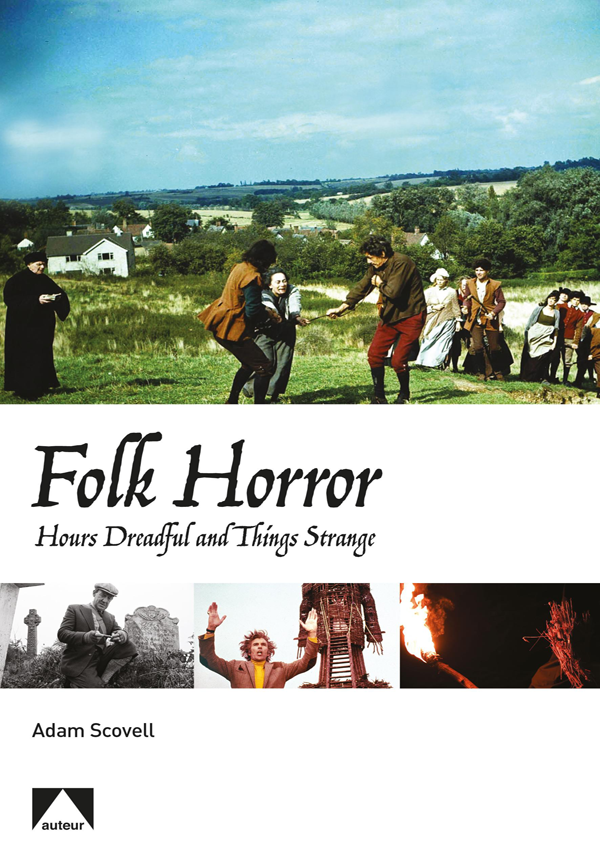

Cover: Witchfinder General Tigon Films; Whistle and Ill Come to You BBC;

The Wicker Man British Lion; Kill List Warp X/Rook Films

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: paperback 978-1-911325-22-2

ISBN: cloth 978-1-911325-23-9

ISBN: ebook 978-1-911325-24-6

Contents

To Jan and Keith, for finding a copy of The Daemons on VHS all those years ago when it was rarer than a cursed crown; and to the memory and work of Mark Fisher.

Threescore and ten I can remember well: Within the volume of which time I have seen Hours dreadful and things strange; but this sore night Hath trifled former knowings. Old Man in Macbeth (1611)

A Cold Evening In Stockport

In October 2013, my head was being gently jolted against a window to the rhythm of a cut-price train. I was exhausted from a long spate of writing and filming but, tonight, I had decided to make the effort and leave my flat in Liverpool for an evening in Stockport. Though the steam on the window had distorted the view outside to a blur of electric lights upon a rich blackness, I had trusted the last minute rush to the ticket machine and quietly assured myself that this strange vision was gradually evolving into an industrial town, typical of those found in the north-west of England. This place of my destination, more famous for viaducts painted by L.S. Lowry, was drawing me to its streets for a particularly special event; a certain screening of a certain cut of a certain film in the presence of a certain director.

The cinema was an unusually busy place that evening, far more so than for its more typical screenings, for the whole building had been taken over by a horror film festival, set to unleash a number of films on an audience ready to lap up the pulp. The walls were covered with black and red paraphernalia of all kinds, and the aisles swam with an excited buzz. I took my seat in one of the period chairs, the shakiness being oddly reassuring rather than worrying. Perhaps, I thought, someone had sat here forty years ago (and two months hence) ready and waiting desperately to see Nicolas Roegs latest mimetic shard of cinema, the gloriously gothic Dont Look Now (1973), but was frustrated at having to first wait through some B-picture, about a wooden man or something. Maybe, just like that evening, the organist would have been doing his utmost musical theatrics, bellowing marvellously on the Compton Organ. The green lights that shone vividly upon its casing made it seem more Dr Phibes than Lon Chaney Snr.

There was mention of other films in the program, yet it mattered very little; there was an appointment to keep with one film alone. Suddenly, a name was dropped out of the white noise of information apropos of Chucky films and the like. The name was Robin Hardy and, for a brief moment, he appeared at the side of the stage. My seat was too far back for a better view at this point but I could see he had come in his typical costume. Rather like the titular lead in Doctor Who, Hardy was a man who seemed to wear the same sorts of clothes in his publicity photos as in real life. Some of my neighbouring viewers looked bemused. Who was this man? And, more importantly, why did the sight of him make certain audience members beam in awe as if in the presence of a papal dignitary? This man in the corner, who looked like the second player from an Amicus film, felt oddly anachronistic compared to his audience; double-breasted blue sailor jacket, RP pronunciation, Cushing handkerchief in top pocket. I was one of these beaming subjects, enraptured in a strange sense of Zen as the lights went down and his film began.

Of course, the film was The Wicker Man (1973). That film of so many strange amalgamations, of so many elements as to require a book of its own to detail its complicated history. This wasnt simply the widely available version, learned by rote in the intervening years through numerous (excessive?) repeat viewings, but a new, longer cut recently discovered in Harvards film archives. The extra footage hugely reframed the film temporally from the version I knew well, the drama of poor Sgt. Howie, played by Edward Woodward, being taken in by the counter-culture pagan window dressings of the community of Summerisle, now feeling very much like taking place over a set number days. The film was fleshed out, somehow impossibly better, a whole new set of cinematic grammar and rhythms to take on board. The exhilaration reached its peak at the final sound of Paul Giovannis score, its last horn being both mournful, fateful and celebratory. The head of the wicker man fell into burning flame, giving way to a vibrant sun at dusk, sinking away behind the horizon of film history; an impossibly perfect final shot whose colours are drenched with the dying embers of the British counter-culture itself.

The ever recognisable logo of the Summerisle sun came up as did the house lights, as if it had lit up the auditorium with its rays of the past. Perhaps we would all leave as pagans in its warm glow. Like the jubilant villagers of Summersle, the audience was in equal rapture, clapping as if Hardy himself had sacrificed Woodward in a frenzied ritual of fire for the benefit of horror cinema as whole. Like a distant cousin of Lord Summerisle, Hardys gentlemanly aura was free to behold as he was asked onto the stage for a brief, seemingly unplanned, Q&A. A few heretics rustled in their seats, impatient for the next film to start. Hardy was rushed through a handful of anaemic questions, those routinely asked of a man sadly only famous for one seriously classic film: a drawn out archaeology of the films cutting history; where the version just screened had differed from the previously existing copy; what was still missing; all answered with the brief but polite hyperbole brought about through years of rote answering, polished to perfection like a pebble.