Table of Contents

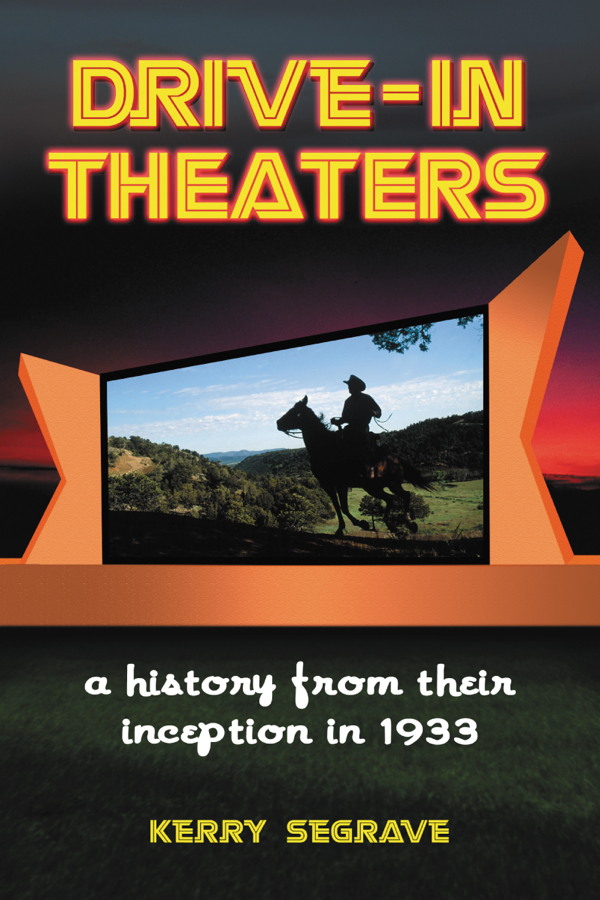

Photos courtesy of BETTER THEATRES, Motion Picture Herald, Quigley Publishing Company, Inc., New York.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Segrave, Kerry, 1944

Drive-in theaters : a history from their inception in 1933 / by Kerry Segrave.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7864-2630-0

1. Drive-in theatersUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

PN1993.5.U6S37 2006

792'.0973'0904dc20 92-50319

British Library cataloguing data are available

1992 Kerry Segrave. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover photograph 2006 PhotoSpin.

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Introduction

When I began to research drive-ins I had no preset ideas or preconceived notionswith the exception of the drive-in's reputation as a passion pit. Letting my research findings guide me in determining what was important in the history and background of outdoor movie theaters, I have tried to strike a balance in this book between the technical aspects of the drive-inwhich didn't fuel its rise but did contribute to its declineand the sociocultural ones; that is, who the audience was, why they went, the response of the community at large to this new cultural force, what factors led to the outdoor theaters' phenomenal rise and, later, to its steady decline toward its inevitable demise, and so on.

While I have included material from around the world, the drive-in is a uniquely American institution. Only Canada and Australia came close to having the intense love affair with drive-ins that America did. This is understandable, given that before drive-ins could spring up all over, a country had to be wealthy; it had to have a good deal of vacant, accessible, relatively cheap land; and the country's inhabitants had to be financially well placed, have automobiles, and enjoy an emotional relationship with their cars. A country that met all the requirements but whose inhabitants regarded automobiles as simply a mode of conveyance to get from A to B would never develop a drive-in industry of any extent.

Along with the pioneering shopping malls, drive-ins led the postWorld War II rush to suburbia. Both catered to families who didn't want to return to the city at nightit was too much of a hassle. But these families were ready to drive to a mall or a drive-in. The latter was ideal, as the family practically didn't have to set foot out of their car once they entered it in their own driveway. Of course, they did set foot outside their car. Rare was the family that could avoid the refreshment counter or the kids' playground or sometimes the adult playground or the bingo or the square dance, and so on. For the drive-in was a family outing involving much more than a movie. Parents didn't have to dress up at all, a fact that was more important then than now. Men in the 1940s and into the 1950s were still wearing suits and hats at what we would regard as the oddest times. The informality of dress that would be one of the lasting legacies of the late1960s youth movement still lay in the future, and its opposite could be a nuisance for those bound up in rules of etiquette. No babysitters were neededtake the kids in their pajamas. There were no parking fees. The kids could play on the mostly free rides. The entire family could eat supper at the drive-in. It was a family outing that satisfied the needs of families to spend time together, to do things together, as a unit. (While teenagers did engage in sexual activity at the outdoor theaters, they formed only a small proportion of the audience.) Drive-in patrons overwhelmingly were families with kids. Solitary adults make up a minority of patrons at indoor theaters; at drive-ins their numbers were much smaller still.

But most of all, drive-ins fueled Americans' love affair with the car. You could drive somewhere, then stay in your car when you got there. The drive-in heyday coincided with the era of the Sunday afternoon drive to nowhere in particular. A trip to a drive-in was something akin to a trip to the beach or a family outing to a low-cost, miniDisneyland. Real Disneylands and their countless more modest variations would, one day, erode the drive-in base. Had the outdoor theaters paid more attention to technical aspects of screening and to showing a higher-quality product, they might have helped to hold this base. Most of all, a trip to the outdoor theater gave Dad an excuse to drive the car around in semirural areas, which had fewer traffic lights and lighter traffic, and he didn't have to try to find a place to park the cara place on a city street or in a garage where it could get clipped by another auto or otherwise damaged.

The drive-in thrived for a time. Anyone who opened an outdoor theater in the 1940s or 1950s made money almost in spite of him- or herself. The film on the screen was largely irrelevant, as long as it was wholesome. Some operators recognized this; some didn't; most didn't care. Because patrons didn't seem to care about the film being shown, operators never banded together in a strong way to try to get a better product to screen. If they could fill the lot with a cheap-to-rent fourth-run film, why try to obtain a costlier first-run product? When quality of product became a more important consideration, it was too late: An unstoppable decline was under way.

Today drive-ins usually screen first-run features, but nobody goes. The family-outing mentality is long gone. Automobiles are much smaller and even less comfortable to view a movie from than were 1950s vehicles. Kids' playgrounds at drive-ins went the way of the dinosaur decades ago. One reason was the litigious American naturetoo many lawsuits and too much money for insurance. The technical aspects of drive-ins were always poor. But again, since the lot was full, why bother to try and improve? (To this day audio and video remain inadequate.) Operators listened to one wild scheme after another that would produce the daylight screentouted for more than thirty yearsand the daylight-containment screentouted for more than twenty. The former would allow all-day screenings at drive-ins, while the latter would do that and contain the image precisely within the lot. This latter issue became important in the 1960s as sex on the screen (visible outside the lot) became more of a community issue than sex in the lot. The miracle screen, of course, never arrived. Even if it had, it would have kept critics at bay and increased profits. It was not proposed to enhance the customers' experience.

The rise of the drive-in was most improbable. Climate dictated that it would be functional in much of this country only for part of the year. And during that part of the year the days were longso long that one show per night was all that was really feasible. They showed a film that had made the rounds and then some by the time it unreeled at the drive-in. Sound quality ranged from abysmal all the way up to poor, with the illusion that the sound came from the actors' lipsalways believable in a hardtop housenever even remotely sustainable outdoors. During the height of summer, for the first ten or twenty minutes, the viewer might have trouble seeing anything at all on the screen, as the operator would start the show as early as possibletoo early to prevent the sun's illumination from washing out the screento try and squeeze in a second show. None of this mattered at all at first. The lot was almost always full.

Next page