978-0-674-98086-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Names: Seo, Sarah A., 1980 author.

Title: Policing the open road : how cars transformed American freedom / Sarah A. Seo.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: Traffic regulationsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Traffic safetyUnited StatesHistory20th century. | AutomobilesUnited StatesPublic opinion. | AutomobilesSocial aspectsUnited States. | Searches and seizuresUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Discrimination in law enforcementUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HE371.A3 S53 2019 | DDC 363.2/32dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018040573

The horseless carriage was just arriving in San Francisco, and its debut was turning into one of those colorfully unmitigated disasters that bring misery to everyone but historians.

Laura Hillenbrand, Seabiscuit (2001)

ON APRIL 11, 1916, eight years after the Model Ts debut and just two years after the perfection of its moving assembly line, the Tucson, Arizona, sheriffs office received a call around midnight about a robbery and assault at Pastime Park, a pleasure resort just north of the city. Three officers jumped into a public service automobile and, on their way to the scene of the crime, saw a car that seemed to be heading toward them suddenly turn around. Suspicious, they sped up to the car and yelled Stop! and We are officers! to no avail. Deputy Sheriff Thomas Johns testified that he then fired his pistol at the wheel to puncture the tire. He fired a second shot, Deputy Sheriff Joseph Wiley fired the third shot, and Police Officer Ramon Salazar followed with a fourth shotall to find out who the parties were in the car. As it turned out, Captain John Bates and his wife, Mary, innocent parties, were driving home from a friends house. One of the shots struck and killed Mrs. Bates. All three officers faced murder charges.

At trial, Captain Bates testified that his car was very noisy and the road rough, which could have described all motor vehicles and country roads at the time. The chains which hold up the tailboard were rattling up and down on the fenders which are over each rear wheel; in fact, every time [he] hit a bump they would jump up and down; the muffler of the machine was wide open, and the exhaust [was] directly in front of the driver, underneath the footboard. The driver of the public service automobile testified that his muffler was wide open as well. With all the racket that the cars were making, it was impossible for the Bateses to hear the officers shouts for them to stop. This, plus the fact of the Bateses actual innocence, convinced the jury that the three defendants had acted beyond their lawful authority and were guilty of murder.

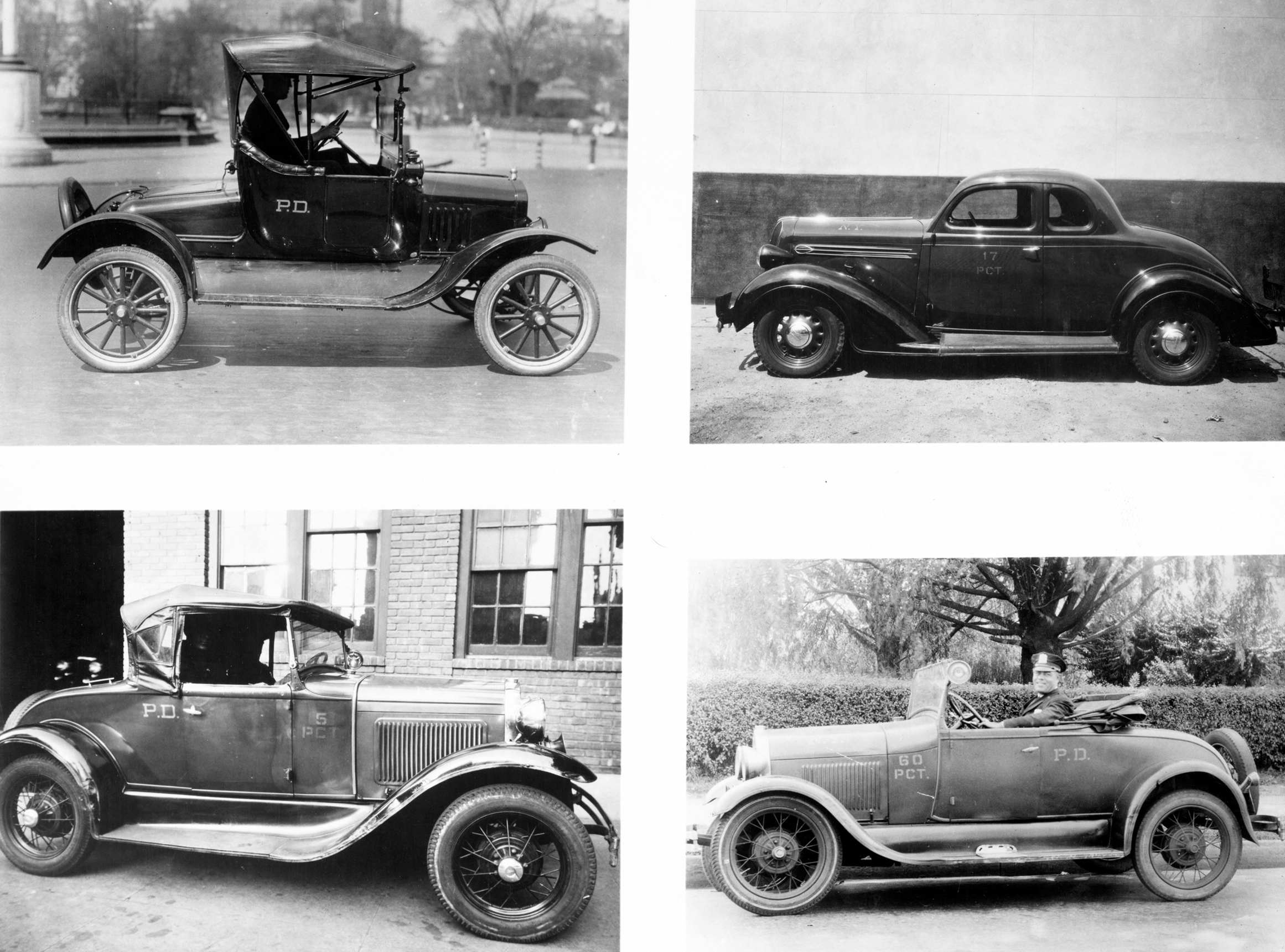

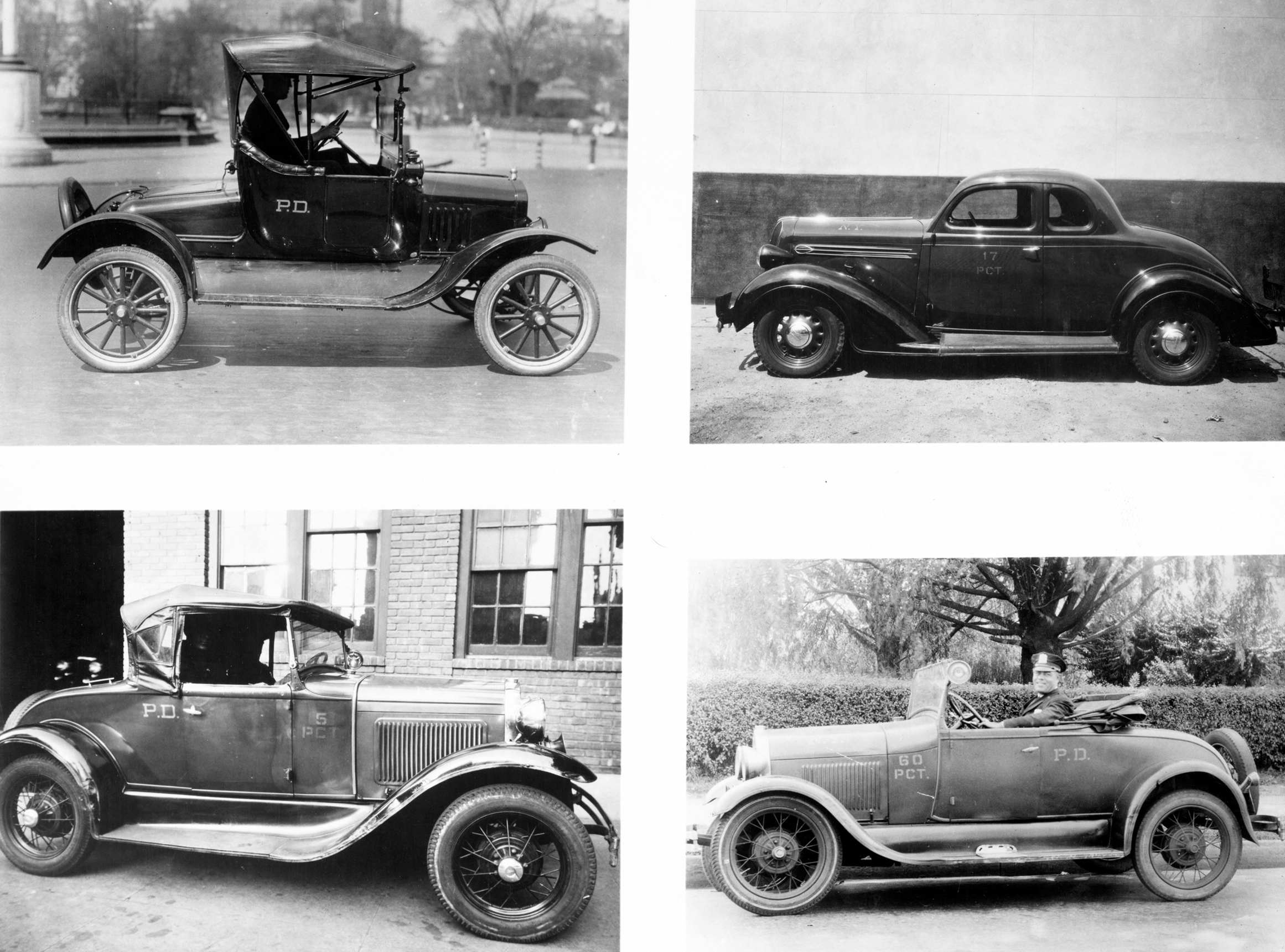

In the case of Wiley v. State, which affirmed the guilt of Deputy Sheriff Johns, whose shot had killed Mrs. Bates, the Arizona Supreme Court maintained that even if the Bateses had heard the shouts and refused to stop, the officers manner of pursuit was more suggestive of a holdup by highwaymen than an arrest by peace officers. The court was not at all being facetious. Recognizable police cars with black and white color blocks would not exist for another two decades, and the first revolving emergency light, the Beacon Ray, would not be invented until 1948. As late as 1934, a consultant recommended that the police department in Dallas, Texas, paint its patrol cars some unusual color, such as fire department red or bright yellow or perhaps with a fine grade of aluminum paint. Without definite identification, his report warned of precisely what had happened to the Bateses: it was not inconceivable that a frightened motorist thinking he is to be robbed may attempt to run away from officers, thereby creating a situation embarrassing and undesirable at its best and which may result in a serious accident or even in the officer, through mistaken identity, actually firing on and killing a reputable citizen. At the time of the Arizona incident in 1916, it was uncommon for public service vehicles to be branded as such. The exceptions had either a sign the size of a license plate attached to the radiator or the initials P.D. painted on the doornothing that drivers could easily discern, especially at nighttime.

New York Police Department cars, circa 1925.

Courtesy of the Alfred J. Young Collection, Museum of the City of New York, X2010.11.11056.

The minuscule markings matched the small size of police forces at the time. When officers shared the task of enforcing the criminal laws with citizens and private patrol services, it would have been unfathomable that respectable citizens like the Bateses might be targets of a police chase. The law reflected this social reality. Because private citizens also pursued, arrested, and prosecuted those who had injured or wronged them, the common law clearly circumscribed the right to arrest in order to distinguish a lawful seizure of a person from a kidnapping or assault. Legal requirements ensured that arrestees would know the exact reason for the apprehension. So when Captain Bates and his wife drove home after an evening with friends, they had every reason to believe, as the court noted, that highway bandits were after them, firing away.

Unfortunately, an intact copy of the officers brief in their defense has not survived the withering effects of time, but we can hazard an educated guess as to their argument. While half of the courts opinion dealt with the different degrees of murder and joint liability, the other half discussed an officers arrest powers. As the court recited, the common law required the showing of a warrant, but it authorized warrantless arrests when an officer reasonably believed that an arrestee had committed a felony offense. The law also allowed an officer to kill a fleeing felon. Given these well-established precedents, the defendants likely claimed that their attempt to make a felony arrest unintentionally resulted in Mrs. Batess death. An especially persuasive attorney would also have pointed out that, with motor-powered vehicles having practically invented the getaway, a rule that officers could not stop cars with gunfire would effectively nullify their authority to arrest suspected felons speeding away.

The Arizona court rejected the officers arguments, and rather than focusing on their right to arrest, it instead elaborated on the Bateses right to drive. The opinion declared that the officers had violated the personal liberty of both Capt. Bates and the deceased, who, having committed no crime, were entitled to proceed on their way without interruption or molestation. This presented a broad statement on the rights of drivers. Entitling them