Acknowledgments

To quote my father:

On a writers way up, he meets a lot of people and in some rare cases theres a person along the way, who happens to be around just when theyre neededperhaps just a moment of professional advice, a brief compliment to boost the ego when its been bent, cracked and pushed into the ground, a pat on the back and words of encouragement....

In my case, there have been so many I could attribute that quote to, and I am humbled and grateful beyond words.

To Charlotte Gusay and Richard Wexler, who were there way back when. And to Dr. Howard Feinsteinfor the guidance all those years ago. I finally heard you when I was able to.

To Dr. Tony Pane and Lee Moon for the life raft and the oars.

To Robert Gottlieb at The Trident Media Group, who called me back the same day I sent the query and passed me along to my wonderful agent, Erica Spellman Silverman, who then introduced me to Marlene Adelstein, editor extraordinaire.

To Sarah Hepola at Salon.comThank You! To Anna Sussman at NPRs Snap Judgment and Dan Lybarger at Huffington Post equal thanks to you.

To Michaela Hamilton, I adore you, and the skilled people at Kensington Publishing.

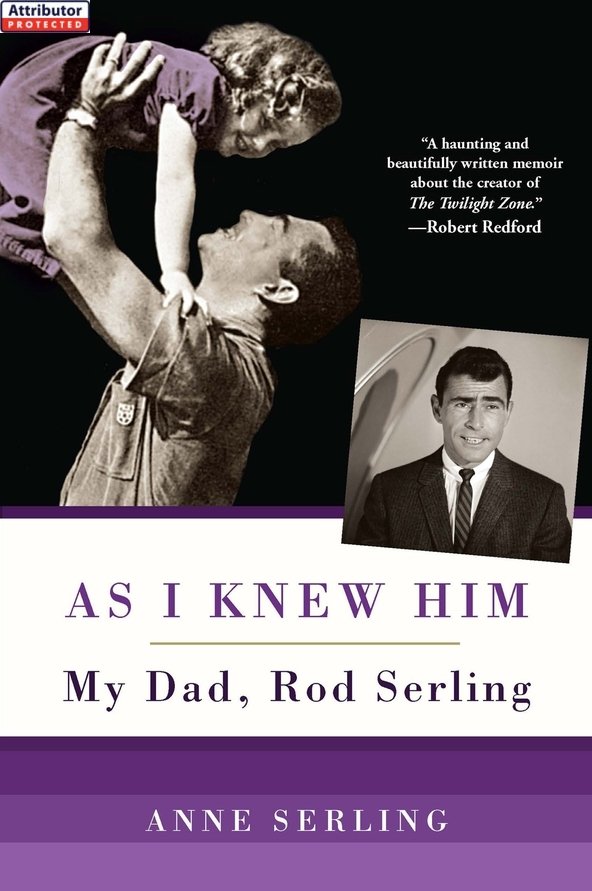

To Robert Redford, Carol Burnett, Alice Hoffman, James Grady, Betty White, Caroline Leavitt, and Dr. Mehmet Oz, for stepping out of their busy lives to touch mine and offer cover quotes.

To Jim Evans, who read the manuscript at its conception and suffered through its many grammatical errors.

To Mark Olshaker, who tirelessly gave me that other dimension of my dad. I am so grateful for all your help. We got it right this time.

To Amy Boyle Johnston, for your incredible research and generosity.

To David Powers, for your keen eye.

To Julie and Rhoda Golden, old friends, great friends. Juliethank you for taking me back to Bennett Ave, and for those wonderful mental snapshots of you and my dad as kids.

For Rochelle Mike, dear friend, who has been there through it all.... Thanks, too, for tirelessly reading every single version of this manuscript.

To Russell Schwen, for all of the moments I would have never known from those dark war days in 1944. Steve Trimm, for your unforgettable words; David Brenner, for the laugh about that flight with my dad to LA; Earl Hamner, for your kind memories, and Mike Newman, for giving me that glimpse of my fathers passionate social conscience way back at Antioch College.

To Susan Charlotte, producer/founding artistic director, Food for Thought.

To Dick Berg, in absentia, for your encouragement and for filling in. And Hal Arlen, too.

For Jennifer Gay Summers, Joan Barnes Flynn, Jane Powers, Pat Amato, Bob Nevin, Colleen Evans, Carolyn Olshaker, Jon and Mimi Gould, Sarah Pitkin, Dorothy Gish, Caroline Cheshire, and Brian Freyprofound gratitude and love to you all.

I am forever indebted and grateful to my friends on Facebook; the ones rediscovered and the ones newly found, to those who shared memories, and to all of you, too, who supported this book. I am so appreciative of your kindness and your friendship.

To Al Magliochetti, for your help with the photo.

To James Latta, for some great suggestions about marketing.

To Jeff and Michele Serling, forever there.

To Andy Polak, president, and Steve Schlich, webmaster, of the Rod Serling Memorial Foundation, the teachers of the Fifth Dimension Program, and Larry Kassan, director of special events at the Rod Serling School of Fine Arts and Video Festivalyou all do so much to keep the legacy alive.

To my mother, for your call of endorsement after you read the manuscript, my sister for your card, and my nephew Ryan.

To Rebekah, Nicole, and Michael, my first wonderful kids.

To Erica, Sam, Alyssa, and to my husband, Doug. You are my lights. My life. And Doug: without your encouragement and belief, I would never have reached the end.

Epilogue

W HEN MY DAD WAS in the hospital, he asked for his tape recorder. A year or so after going to his grave, I removed the tape from my desk drawer, closed myself away in my bedroom, took a deep breath, and finally pushed PLAY and listened for the first time. There was background noisepeople talking in the hall, doors closing. His voice was not the strong, dramatic, resolute one the public has come to know, and for a moment, so overwhelmed, I had to stop the tape, saddened by the weakness of his voice. I thought of him making this recording, and for an instant could see him so clearly, his black wavy hair against that white pillow. I could see him sitting up wearing a hospital gown pushing the buttons on his recorder that I pushed now.

There were long, painful pauses between his thoughts, and he turned the machine on and off several times before he began:

I thought I might jot down certain reflections that relate to what a man feels like following a heart attack. The first thing I notice, as I speak into this thing, is I feel seriously devoid of energy, something I have never lacked for...

He pauses and then,

The days are infinitely longer in the hospital, not only in chronology and in time passing but also in the actuality of the event. They start early and last a long time. And there is so little during the course of the days activity to punctuate the regimen, that you get more of a sense of the prolongation of the day.

Another item: I discovered that I dont nearly have the fear of death that I once had. What I do have is the terrible awareness of how little time there is to accomplish so many of the things that you want to accomplish.

The other thing that seems accentuated, almost to a point of distortion, is the need, the desperate need you have of family, of loved ones. When it appeared possible I might not make it, I didnt feel so much the awful awareness of, Jesus Christ, its going to be me ending the earth. What seemed to me the most predominant in my fears was that it would be the relationships that would end.

My father makes note, too, of the humorous aspects of hospital living, and here, he laughs.

The fact that, like all good dramatists, one always, I suppose, thinks subconsciously or at least if not preoccupiedly with the way that it happens, the moment of the death. Whether it be Valhallian in some way, semi-heroic, at least with the sense of the drama... And how the hell did I go? Fucking around, trying to start a rototiller, and I find that is an ignominious way of going. Lightning maybe should strike me, or I should invent some incredible new Lutherburbankian plant at that given crashing moment of incredible pain as I look up and say, Okay, God, now you can take me, because I have discovered this new breed of plant. But no, no. Nothing that heroic. All I was able to accomplish was to start the engine of the rototiller, nothing more than that. Nothing more contributory.

Thirty-five years after my fathers death, four decades after The Twilight Zone went off the air, its parables are still relevant today. But he did not believe he would be remembered. Ive pretty much spewed out everything I had to say, none of which has been particularly monumental, nothing that will stand the test of time ... Good writing, like wine, has to age well, and my stuff is momentarily adequate.

In what was to be my fathers final interview, he was asked what he wanted people to say about him a hundred years from then. He responded, I dont care that theyre not able to quote any single line that Ive written. But just that they can say, Oh, he was a writer. Thats sufficiently an honored position for me.