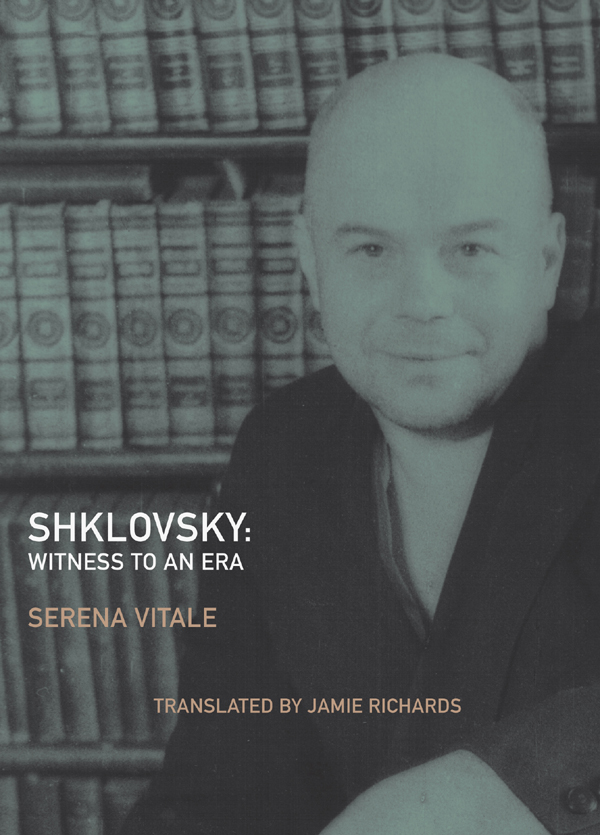

Shklovsky: Witness to an Era

SERENA VITALE

TRANSLATED BY

JAMIE RICHARDS

Contents

O N THE INFINITY OF THE NOVEL . A RT HAS NEITHER BEGINNING, MIDDLE, NOR END. E PILOGUES ARE CLOYING LEFTOVERS. A RT DEALS ALWAYS AND ONLY WITH LIFE.

T HE MEMORIES BEGIN . C HILDHOOD IN P ETERSBURG . H OW TO EAT BLINTZES . D IGRESSION ON THE DRAWBACKS OF HAVING A SECRETARY . S HKLOVSKY MEETING M AYAKOVSKY, HE DOESN T REMEMBER EXACTLY WHEN; THE BEGINNING OF THEIR FRIENDSHIP . T HE FUTURIST EVENINGSTHE TECHNIQUE OF SCANDAL . B AUDOUIN DE C OURTENAY . P OETS SHOULDN T BE ALLOWED TO DIVORCE . S EMINARIANS AND CARPENTERS DUKING IT OUT ON THE ICE.

Y OUNG PHILOLOGISTS MEET AND DISCUSS LITERATURE AT THE U NIVERSITY OF P ETERSBURG . T HE BIRTH OF FORMALISM . L EV J AKUBINSKY . Y EVGENI P OLIVANOV . P OETRY AND TIME : T HE B RONZE H ORSEMAN . P OETRY AS THE DEEP JOY OF RECOGNITION . S HKLOVSKY, SAYS B LOK, UNDERSTANDS EVERYTHING . Y URY T YNYANOV . B ORIS E IKHENBAUM . H OW TWO EX-FORMALISTS ARGUED THE DAY A KHMATOVA DIED . D ERZHAVIN S ARRIVAL SPELLS THE END OF FORMALISM . M AN S DESTINY IS THE MATERIAL OF ART . W HICH HAS TO BE SHAKEN UP ONCE IN A WHILE, LIKE A CLOCK THAT STOPS TICKING . O N THE FUTILITY OF LOOKING AT FLAGS.

K HLEBNIKOV , F ILONOV, AND A PAINTING THAT REFUSES TO HANG ON THE WALL . M ALEVICH S SQUARE . F EBRUARY 1917 . M EMORIES OF WAR . A STOMACH WOUND . A KISS FROM K ORNILOV . R USSIA AND A SIA . R USSIA AND E UROPE . E SENIN IN VALENKI . M AYAKOVSKY HAS THE LAST WORD: THE PEOPLE KNOW HOW TO DRINK.

C IVIL WAR IN P ETROGRAD, DEAD HORSES IN THE STREETS . T HE SHIP OF FOOLS . T HE S ERAPION B ROTHERS: LOTS OF YOUNG PEOPLE, SOME IN THEIR TEENS . R EVOLUTION = DICTATORSHIP OF THE A CADEMY OF S CIENCES . M EYERHOLD, THE OLDEST DIRECTOR IN THE WORLD . H IS ARCHIVES SAVED BY E ISENSTEIN . T WO I NSPECTORS G ENERAL . Z OSHCHENKO TURNS ON SOME DISCONCERTING LIGHTS . B ERLIN . A MISTREATED HAT . A N UPLIFTING SONG.

T HE BIRTH OF S OVIET CINEMA IS COMPARED TO THE CREATION OF THE WORLD . T HE L ETATLIN: A DREAMING MACHINE . T HE WEAPON OF PATIENCE . M AYAKOVSKY DIDN T WANT DEBTS . D IGRESSION ON P ASTERNAK S POETRY , B ULGAKOV S NOVELS . S HKLOVSKY BEGINS TO WORK IN CINEMA, HE WRITES INTERTITLES AND THEN SCRIPTS . H E MEETS E ISENSTEIN . W HAT WAS THE ROLE OF DISHES IN THE O CTOBER R EVOLUTION? S OME FILMS S HKLOVSKY WROTE : B Y THE L AW , B ED AND S OFA , M ININ AND P OZHARSKY . S HKLOVSKY TEARS APART T ARKOVSKY S A NDREI R UBLEV . A N UNUSUAL EDITING JOB . A N EVEN MORE UNUSUAL WRITING JOB.

T OLSTOY BEGINS TO WRITE . A H ISTORY OF Y ESTERDAY . F OR SOME REASON S HKLOVSKY TORE UP THE FIRST VOLUME OF T OLSTOY S C OMPLETE W ORKS . T HE YOUNG T OLSTOY LEFT FOR THE C AUCASUS WITH AN E NGLISH DICTIONARY, A FLUTE , T HE C OUNT OF M ONTE C RISTO , AND A SAMOVAR . A N ANCESTOR OF OURS LEFT OUT OF Z OO, OR L ETTERS N OT ABOUT L OVE . F RIGHTENING, POETIC DREAMS . W HAT DOES REALISM MEAN?

T HE WORD . P OETRY OF WORDS AND POETRY OF LETTERS . M AYAKOVSKY LOVED THE RADIO . A N UGLY, STUPID BOX . O NE MUSTN T FEAR THE FUTURE . T OLSTOY GETS EDITED . T HE OLD SCHOLASTICISM AND THE NEW . T HE LIVING R USSIAN WORD.

Pushkins Button

OTHER WORKS BY VIKTOR SHKLOVSKY IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Literature and Cinematography

Knights Move

Sentimental Journey: Memoirs, 1917-1922

Zoo, or Letters Not about Love

Theory of Prose

Third Factory

Mayakovsky and His Circle

Leo Tolstoy

Bowstring

Energy of Delusion

The winter of 1978, in Russia, was among the coldest of the century. That late December in Moscow, no one spoke of anything elseon the metro, in the offices, in the shops. Little old men and women, emerging from their capsules of frozen vapor, discussed it incessantly: when had it ever been this cold? In 1915, 17, 25?

This was a question I could put to Viktor Shklovsky, to his eighty-six-year-old memory, witness to so many climates, meteorological and otherwise, as I told myself on my way to his house for the first time.

I wait a few minutes in his book-crammed study, one of the two rooms that make up the writers home. On a massive walnut table, haphazardly stacked, Plato, Mayakovsky, Tolstoy, books on semiotics, on structuralism. Finally, preceded by the remarkably kind and ever attentive lady of the house, Serafima Gustavovna (Shklovskys second wife), the patriarch makes his grand entrance, swathed in a stately, impeccable robe, outfitted with a beret for the cold and a cane for supporthis steps are a bit labored, but theres a twinkle in his eye.

We introduce ourselves. Then, the formalities: I begin reading the publishers contract, which Shklovsky has to sign for the interviews. He listens attentively to my translations of the usual clauses, and, with sublime navet, seriously considers each one. After a few minutes he begins to roar: Why should he grant rights for fifty years? Who are these alleged heirs it talks about? What television or film use would ever be made of this book? How can anyone write a book in ten days (the amount of time I had proposed)? After a while of this, his indignation draws upon the cautionary tales of literary history: this is a binding contract, like the ones Stellovsky ruined Dostoyevsky with... Never in a million years! A television crew that, unfortunately, has chosen this same day to film Shklovsky at work, comes in and stands frozen in the doorway. Shklovskys contentious temper has been unleashed, and the hapless camera crew has walked right into it. They try in vain to camouflage themselves among the books. Young man, Shklovsky yells, have you read Pushkin? People need to read our classics more often...

When I finally manage to get a word in, explaining that its a standard contract, that he wouldnt have to write a book but simply answer my questions, granting me two or three hours a day, the situation begins to improve. The next day, the irate patriarch is already tame, even sweet at times...

After a few days, when I had told him about my work, about the authors I love and study, he was already calling me a dear friend and saying that he was happy about these meetings of ours (every day from one to three) because hethe madman of letters and raving orator, as he described himselfwas energized by having someone to talk to.

After our official conversations, we would keep talking, with the tape recorder offabout everything, everyday problems, the situation in Italy, Russia, about family, old and faraway friends, film, literature, the new Pope... In fact, in those moments it was the interviewee asking the questions: Whats happening with... ? What are people saying about... ? His curiosity was voracious. Shklovsky was like an eighty-six-year-old boy.

Once in a while, when he was the one talking, old wounds would be reopened, tapping into a well of private memories, difficult experiences, regrets, and bitterness that I, by that time welcomed in their home as a friend, now keep just for myself.

We became friends.

I treasure the memory of these off the record chats we shared during our ritual coffee (Shklovsky delighted like a child at the opportunityoffered by my presenceto take a break from his no-coffee diet) in the second room; while in his work room, amid the sundry wall decorations, hung a wonderful photo of Shklovsky and Mayakovsky in neck-high bathing suits, and a portrait of Osip Mandelstam.

Why an interview with Viktor Shklovsky? The idea, when it was suggested to me, appealed immediately. It would be a chance to fill in some of the gaps in the (albeit plentiful) autobiographical writing left by Shklovsky, witness to an era that never ceases to fascinate me and that always offers new ideas for reflection and research.

Next page