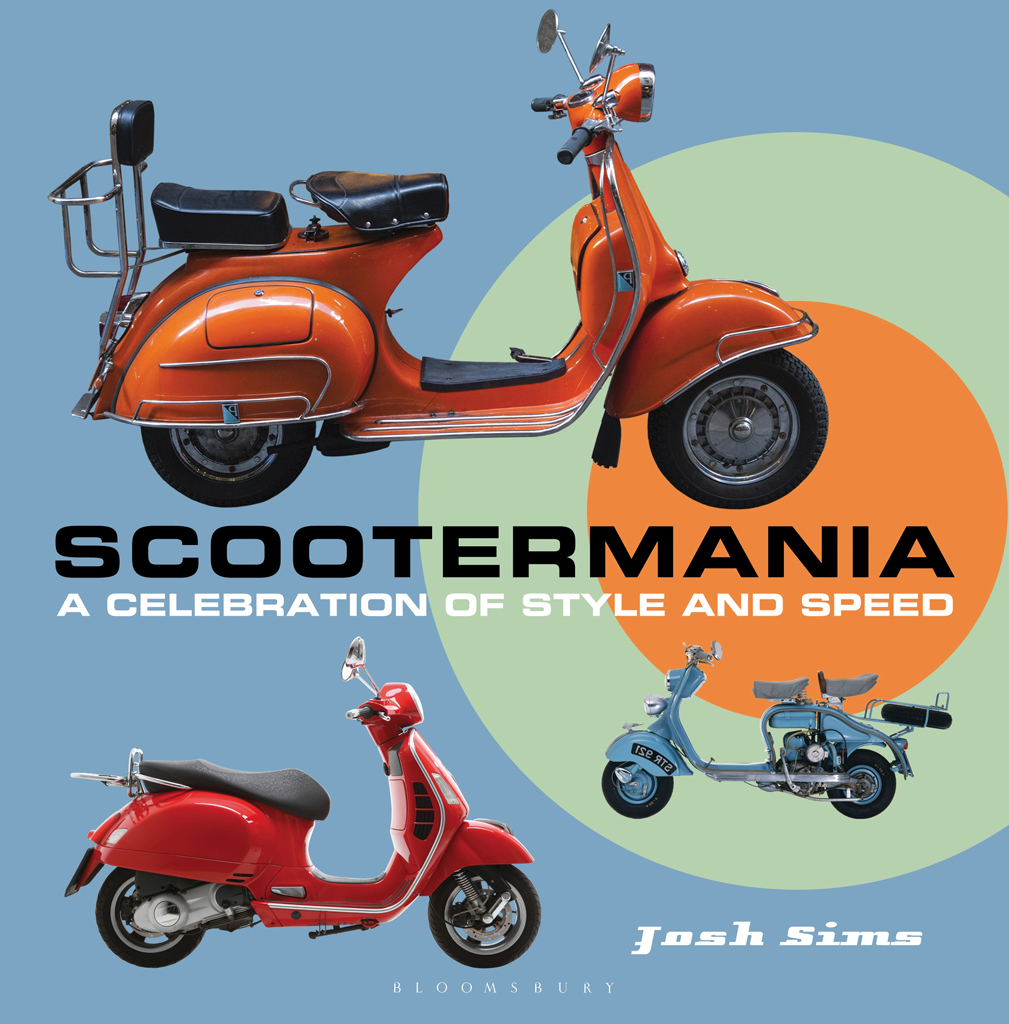

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

www.bloomsbury.com

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

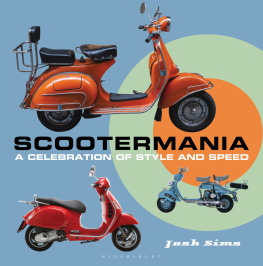

Josh Sims, 2015

Photographs as noted on p.176

Josh Sims has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act,

1988, to be identified as Authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, or any information storage

or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organisation acting on

or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication

can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-8448-6277-1

ePDF: 978-1-8448-6279-5

ePub: 978-1-8448-6278-8

Design by Nicola Liddiard at Nimbus Design

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

C ontents

CHAPTER 1.

History and design

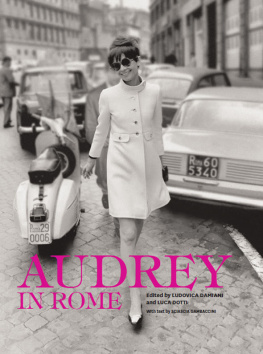

In terms of public image, the scooter has long played second fiddle to the motorcycle. If the motorcycle in large part due to Hollywood myth-making, from The Wild One to Easy Rider suggested the romance of the open road, the scooter suggested another breakdown at the side of the road; if the motorcycle suggested the machismo of the outlaw figure, the scooter, in contrast, at times suggested prissiness and the feminine; if the motorcycle suggested power, the scooter suggested pootling, even at full throttle. The scooter is all small wheels and pop colours. The scooter is fun.

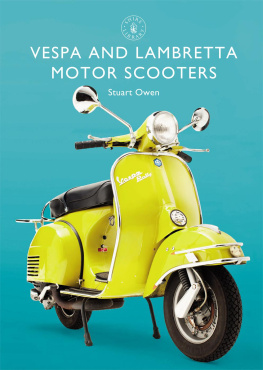

Of course, there is a large dose of stereotype in the readings of both kinds of machines and at heart both have provided the same thing: escape, independence, mobility and a certain kind of cool. Indeed, while, over its post-Second World War boom times the scooter has attained a smaller global following than the motorcycle, arguably it has inspired a more ardent following, especially given the relatively tiny and often troubled industry extant to supply it. It has perhaps also inspired more affection among the general public, precisely for its smallness, in scale, noise and attitude. Scooters can be cute. Even their name scooters sounds cute, with, similarly, the dominant companies behind them, most famously Piaggio with the Vespa and Innocenti with the Lambretta, suggesting a foreign exoticism and Italian chic, one that thankfully has survived globalisation.

Not, for sure, that these were the only manufacturers and not by a long way. While longevity and pop culture have ensured that these two names have become bywords for the scooter even generic terms akin to Hoover for all kinds of vacuum cleaners many other companies were involved in scooter production. The scene was set with much of Europe on the long road to post-war reconstruction, rationing still in place and cars unaffordable to buy and expensive to run for many which is perhaps one reason why scooters generally failed to catch on in consumer booming America. Such was their expected appeal in the 1950s particularly that even motorcycle manufacturers dipped their toe in the waters.

One of the most attractive, and, it must be said, Vespa-like, designs of the 1950s, for example, was the British-made 175cc or 250cc Triumph Tigress. Its feminised name hinted at the market that Triumph perhaps had in mind. Tiger would have been far too macho applied to a scooter. In 1952, even future super-bike manufacturer Ducati produced a scooter, the rather more sexily named Cruiser. Ducatis, naturally, packed more power than most, housing an overhead-valve 175cc engine.

Yet throughout the scooters history, its most successful variants have been designed and built by specialists. And, it might be added, attracted a specialist audience, too, who understood and appreciated that a scooter was not a poor cousin to the motorcycle, but something altogether different: progressive, modernistic, accessible and fashionable.

A vintage scooter in a village square in Lazio, Italy, perhaps the nation where the scooter has been most at home.

N ew wheels

THE FIRST GENERATION

While the scooter may be most readily associated with the names Vespa and Lambretta and the story of Italys post-war social and industrial restoration, its history is much older and deeper. Indeed, the decades immediately following the Second World War are often characterised by historians of transport as the scooters second wave, the first dating back to 1916, when a roughly 10-year period saw the first vehicles of this kind take to the streets and sometimes successfully. Many of the manufacturers who created, and later developed, the scooter market hailed from the aviation industry, and used their technical knowhow in one field of advanced engineering to create another. Arguably, it was not being hidebound by the rules of automobile design that allowed them to be so inventive.

US postmen, pictured here in 1917, with an early version of the scooter.

Certainly the first wave was a boldly inventive time, both mechanically and stylistically, in large part because, unlike the motorcycle which was by this time established in both form and intention the scooter was genuinely new. It was not merely a motorised bicycle (one basic distinction between scooter and moped is that it is only the latter than retains pedals), but a fresh form of mobility entirely, most widely characterised by having a step-through body. The result was that, within that general characterisation, these early years of the scooter witnessed both a huge diversity of looks and new approaches to engineering. Most notably, this was the first time that motors would be developed especially for the machines, whereas typically a new design of motorcycle would be built around a pre-existing power plant.