Arthur & Sherlock

To

George Gibson

with admiration and affection

By the same author

NONFICTION

The Adventures of Henry Thoreau:

A Young Mans Unlikely Path to Walden Pond

The Story of Charlottes Web: E. B. Whites Eccentric Life in Nature and the Birth of an American Classic

In the Womb: Animals

(Companion to a National Geographic Channel television series)

Apollos Fire: A Day on Earth in Nature and Imagination

Adams Navel: A Natural and Cultural History of the Human Form

Darwins Orchestra: An Almanac of Nature in History and the Arts

ANTHOLOGIES

The Phantom Coach: A Connoisseurs Collection of Victorian Ghost Stories

The Dead Witness: A Connoisseurs Collection of Victorian Detective Stories

Draculas Guest: A Connoisseurs Collection of Victorian Vampire Stories

The Penguin Book of Victorian Women in Crime:

Forgotten Cops and Private Eyes from the Time of Sherlock Holmes

The Penguin Book of Gaslight Crime:

Con Artists, Burglars, Rogues, and Scoundrels from the Time of Sherlock Holmes

Arsne Lupin, Gentleman-Thief by Maurice Leblanc

The Annotated Archy and Mehitabel by Don Marquis

Contents

What clue could you have as to his identity?

Only as much as we can deduce.

From his hat?

Precisely.

But you are joking. What can you gather from this old battered felt?

Here is my lens. You know my methods.

SHERLOCK HOLMES AND DR. WATSON

IN THE ADVENTURE OF THE BLUE CARBUNCLE

A shiny brass plate suspended from a wrought-iron railing along the street proclaimed

DR. CONAN DOYLE

SURGEON

Patients wishing to consult Arthur strode along Elm Grove until they were three doors from its west end, where it met Kings Road. The sign stood before number 1, Bush Villas, the first of two narrow three-story houses squeezed between and sharing walls with other establishments. On the left, as seen from the street, rose the brick bell tower and elegant arching windows of the newly renovated Elm Grove Baptist Church. On the right stood the handsome curving faade of Bush Hotel, which advertised as both Commercial and Family and which boasted the largest billiard saloon in Southsea. Always preoccupied with sports and physical activity, broad-shouldered Arthur enjoyed playing billiards in the hotel and playing bowls on the broad green behind it.

The flats large, square front windows faced almost due north and thus received strong light without glare. Patients entered through the arched entryway on the left, adjacent to the church, where the front door opened into a hall that led to a small waiting room and a consulting room on the ground floor. Stairs led up to the surgery and a private sitting room, and another flight climbed to a pair of bedrooms on the top floor, which patients never saw.

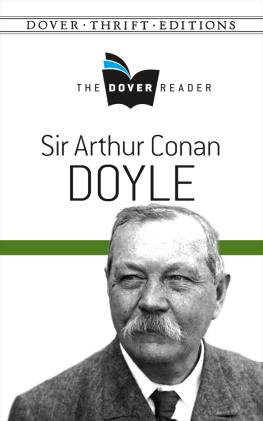

In early 1886, Arthur Conan Doyle was a few months shy of twenty-seven. For less than four years, he had operatednot always with successa medical office in Southsea, a bustling residential section of Portsmouth, England. Lacking the funds to buy into an established practice, he had resolved to build his own from scratch, and after a little research he decided upon Portsmouth as a promising setting. In local sporting circles and scientific societies, he was known for his sociability and his hearty, infectious laugh.

Four years after settling here, he was no longer so poor that he had to buy creaky chairs and a faded rug on credit to furnish the sitting room. He did not sleep in his ulster, as he had for the first couple of weeks at Bush Villas when he owned no bed linens. He did not have to cook bacon on a little platform rigged on a wall over the gas jet. He no longer borrowed money from his mother back home in Edinburgh. Gradually his income had climbed, but his fear of creditors had faded only when he married the petite and soft-spoken Louise Hawkinsnicknamed Touiewith whom he fell in love after caring for her younger brother during his last days. Patients still trickled in, but Arthur no longer peered anxiously down through the wooden blinds to count passersby who stopped to read his brass nameplate.

They were not rich, Touie and Arthur, but they were comfortable. The most important luxury that Arthur could now afford was more opportunity to write. Since moving to Southsea, he had spent as much time as possible at his desk, upstairs in the space to which patients were never admitted. He filled page after page with his neat, small script. Gazing thoughtfully out the window beyond his desk, he became so intimate with the view from his study window that later he wrote it into one of his novelsthe sound of rain striking a dull note on fallen leaves and a clearer note on the gravel path, the pools that formed in the street and along the walkway, even a fringe of clear raindrops clinging to the underside of the bar atop the gleaming gate. With the windows open in warm weather, he could smell the damp earth.

Here Arthur wrote stories of mystery, adventure, and the supernatural, and rolled them up and inserted them into mailing tubes for the postman. Having once thought of these unsolicited writing efforts as returning quickly and reliably like carrier pigeons from the magazines and newspapers to which he sent them, he gradually met greater success. He also wrote articles about his hobby, photography, ranging from colorful accounts of steaming along the coast of Africa to technical advice on how to prepare lenses.

In the style of the time, however, most of his stories were printed anonymously, resulting in a growing reputation with editors while he remained unknown to the public. Finally he decided that he must write a novel. Only his name on the spine of a long work of fiction, he told himself, could begin to build readers awareness of him. He had written one awkward little novel whose only copy had been lost in the mail, but he was determined to try again.

He was drawn to detective stories out of his own interest. He had long admired the logical mind of Edgar Allan Poes unofficial detective C. Auguste Dupin. He had enjoyed the adventures of mile Gaboriaus eagle-eyed police detective Monsieur Lecoq. The bold man-hunters of penny dreadfuls, Charles Dickenss Inspector Bucket from Bleak House, Wilkie Collinss Sergeant Cuff from The Moonstone, Anna Katharine Greens more recent New York policeman Ebenezer Gryce from The Leavenworth Casemany such detectives already cavorted in Arthurs imagination when he decided to create his own.

He had no experience with real-life detective work. As he turned over plot ideas in his mind, however, he recalled his years as a student at medical school in Edinburghhis birthplace, to which he returned in 1876 at the age of seventeen, after boarding schools in England and Austria. And especially he thought about his favorite professor, a short, hawk-nosed wizard named Joseph Bell. A surgeon and a brilliant diagnostician, he had impressed his young student in many ways. Arthur had always admired Bells oracular ability not only to diagnose illness but also to perceive details about patients personal lives. Arthur thought of the professors quirky habitshis intense gaze darting at fingertips and cuffs to read a patients history of work and play, his attention to subtleties of accent, to mud splashes on boots. He recalled Bells commanding way of speaking with such confidence that he won over every person who argued with him.

As a detective, Arthur thought, Joseph Bell would have approached crime-solving with systematic, modern knowledge. He would need practical experience in chemistry and forensic medicine, as well as encyclopedic knowledge of the history of crime. He must attend to the large implications of small details. Such a character would be a new development in crime fictiona scientific detective.