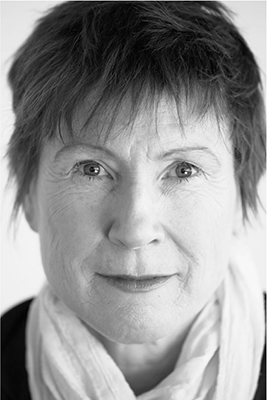

Photo by Grant Sparkes-Carroll, courtesy of the Sydney Theatre Company

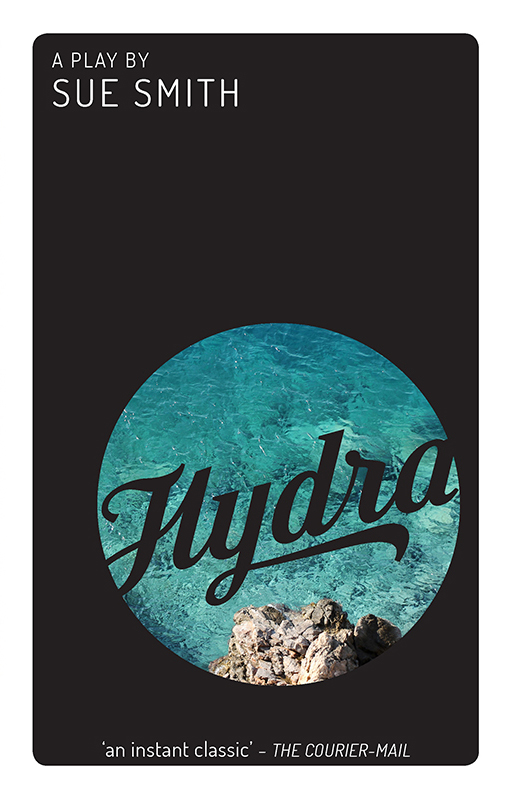

Hydra

SUE SMITH is a multi-award-winning screenwriter, play-wright and script editor. Her numerous works include Kryptonite, Machu Picchu , Brides of Christ and many more. Sue was the STC Patrick White Playwrights Fellow for 2018 and received the 2018 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Australian Writers Guild. In 2019 her new play Hydra was produced by Queensland Theatre and State Theatre Company South Australia.

Hydra

A PLAY BY

SUE SMITH

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Sue Smith 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act , no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Any performance or public reading of Hydra is forbidden unless a licence has been received from the author or authors agent. The purchase of this book in no way gives the purchaser the right to perform the play in public, whether by means of a stage production or reading. All applications for public performance should be addressed to Camerons Management, PO Box 848, Surry Hills, NSW 2010, Australia; tel: +61 2 9319 7199; email:

ISBN: 9781742236544 (paperback)

9781742244600 (ebook)

9781742249094 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Original playscript series design by Sandy Cull, www.sandycull.com

Cover image Shutterstock/Katarina Palenikova

Contents

Introduction

Sue Smith

I pat myself on the shoulder for having had the guts to leave my conservative upbringing and search for a more bohemian touch of life. I suppose thats what life is all about, to find out who you are and what you can do with this gift of being alive

Dinnie Pedersen, reflecting on Hydra in the 1950s and 60s

to find out who you are and what you can do with this gift of being alive This is a story about choice: the choices we make and the reality that any choice, courageous or meek, wild or suffocatingly safe, will have consequences.

Charmian Clift and George Johnstons dream of a life of creative freedom on a Greek island first caught my attention over twenty years ago. Their love story fired my imagination, as did the scale of their ambition, and the magnificence of the writing they created. The scale, too, of their tragedy. The two met when George was a lauded war correspondent and Charmian a young journalist and fledgling fiction writer. George left his wife and daughter for Charmian, and they began a family together. In 1955, when Charmian was pregnant with their third child, they moved the family to Greece, and then, in 1956, settled on the island of Hydra. I was held captive by the myth. But the very thing that makes a myth so powerful is that it speaks to the lives we ourselves are living. There is evidence that Charmian and George, to an extent, created and shaped their own myth. But dont we all, in the way we frame our lives to our families, friends and the wider world? And, indeed, we create myths for ourselves. So many of us dream of striking out for individuality and freedom from convention; of escaping the drudgery of the workaday world; of rejecting the grubby commercialisation of modern life in the big cities. We dream of allowing ourselves to be exposed to beauty, and to risk. But for most of us, these are only dreams. Charmian and George actually did it. In the most socially conservative of times they threw every type of caution to the wind and leapt off the cliff in an attempt to fly. In Charmians own exquisite words, they sought to build a good rich life from the raw materials of the man, the woman, the children and the talents we could muster up between us.

And for a brief shimmering moment, they succeeded

The CliftJohnston family story is quintessentially Australian. It illuminates the need felt by so many Australians, certainly of their generation, but even now, to expatriate in order to discover their true identity. It also reveals the complexities of how two passionate creators negotiate living together, how one career will so often be subsumed by the other, how difficult it can be to strike any sort of healthy balance: a difficulty often lived now as it was then. And ultimately, it shines a light on how the following generation is affected by the choices of the first.

It can be argued that here in Australia we tend not to celebrate our artists in the way other cultures do. We admire their work, but we dont often look at the life that created the work. With these two writers, in particular, the work is informed absolutely by the life, and the life is sculpted around the needs of the work. The two echo their melody back and forth.

Attempts to grasp the essence of the Clift Johnston story have occupied passionate and searching minds for decades. Questions arise. What went wrong? Was such pain and heartache necessary to create the work? Was it all worth it? And what of the damage inflicted upon the next generation? There are many answers to these questions. And there are none. Poverty, isolation, illness, exile, alcohol, jealousy and infidelity all played their part. Perhaps the age and experience gaps between Clift and Johnston are key to partly answering some of these questions. She was always in the junior, subordinate, acolyte role: sitting at his feet, as it were, either in a Bondi lounge room or on a stone step in Greece. There is also, of course, Charmians grief in having given up her first daughter, Jennifer, for adoption. And Georges loss through divorce, and the resulting distance between him and his own daughter, Gae. For George also, ravaged by pulmonary tuberculosis, the sheer horror of literally having to gasp for each breath, and of no longer being able to make love to the woman you adore. The pain of unfulfilled literary dreams.

I wonder, also, whether the scourge of clinical depression may have reared its ugly head earlier in Charmians life and not just in those final couple of years. The 1960s did not recognise depression and so Charmian may have been forced to self-medicate with alcohol. Then theres the vicious cycle of alcoholism alcohol itself being a depressant, resulting in increasing consumption, in turn leading to further depression Many answers. And none. Perhaps the real truth is even starker that its simply not possible to live a dream forever And how can any of us answer the other question: was it worth it? I can only pose that to an audience and allow them to decide for themselves.

When dramatising any story, it is necessary to edit, condense and synthesise. It is also often necessary to shift the chronology of real events, which I have done. There are many details I was reluctantly forced to omit, so I would encourage anyone whose attention is caught by this story to read, first of all, Clift and Johnstons own work, and also the splendid biographies by Garry Kinnane and Nadia Wheatley. Wherever possible, I have used Georges and Charmians own words far more potent and transcendent than any tool I could pull from the dramatists kit. I am immensely grateful to the Clift and Johnston estate for allowing me to make extensive use of Charmians

Next page