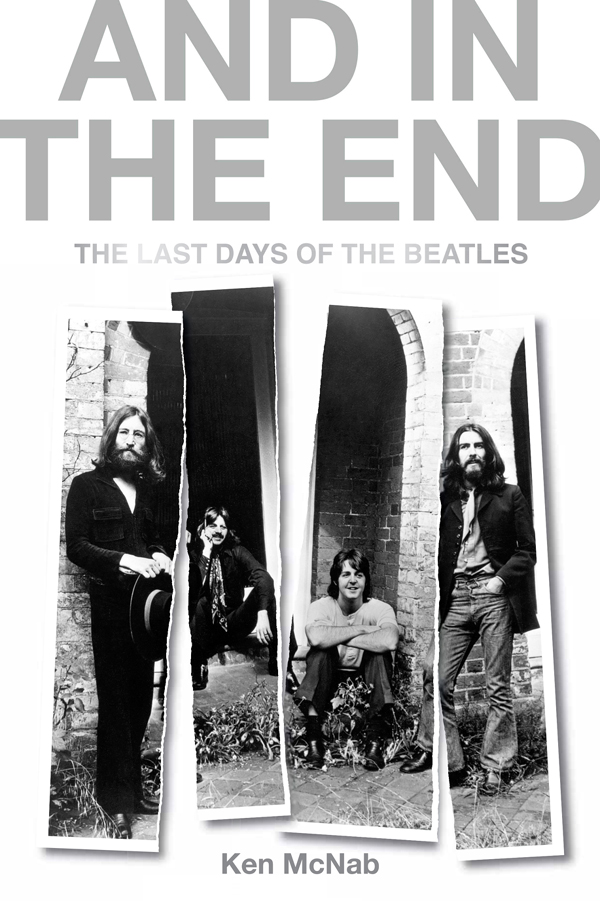

AND IN THE END

AND IN THE END

THE LAST DAYS OF THE BEATLES

Ken McNab

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright Ken McNab 2019

The right of Ken McNab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders. If any omissions have been made, the publisher will be happy to verify these in future editions.

ISBN 978 1 84697 472 4

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 177 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by Studio Monachino

For the other half of the sky in memory of

Bridget, Kieran and Brian

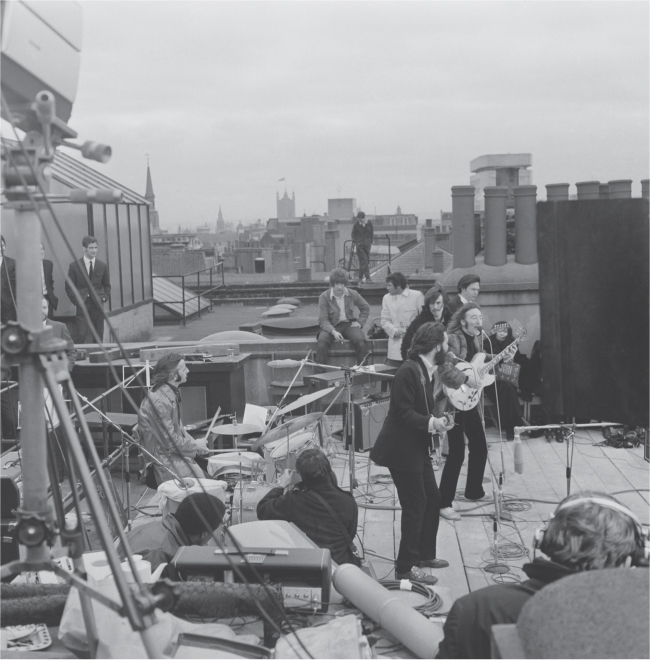

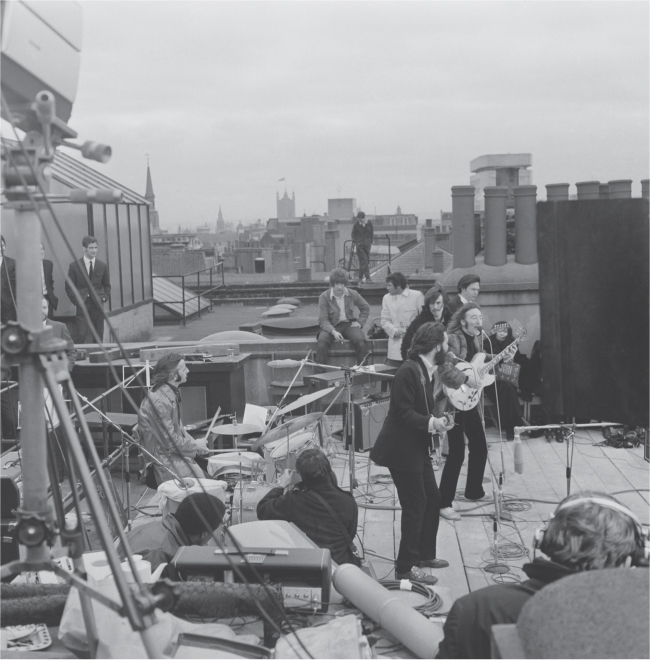

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

All four Beatles climbed the stairs to the roof of the Apple building in Savile Row for their last public performance played in the teeth of a bitter wind that served as the climax to Michael Lindsay-Hoggs film documentary Let It Be.

JANUARY 1969

All the rainbow colours of the outside world seemed to have been extinguished, replaced by a grim, cheerless darkness. The only sounds came from the heavy footsteps of two men Mal Evans, the faithful roadie, and Kevin Harrington, the faithful gofer lugging in guitar cases, amplifiers and drums, the sound of their heels echoing in the stillness. The guitars were positioned in a circle beside three chairs. Already in place stood a Blthner piano. The drums were then mounted on a high-riser, the black lettering with the familiar dropped T a clue to their owner.

Close by, people worked stealthily, checking camera angles and light meters. Men with headphones tested their audio equipment, checking noise levels. Snaking all over the floor and around the chairs were seemingly endless lengths of cables and wires. On the morning of 2 January, the sound stage at Londons Twickenham Film Studios was a hive of muffled activity. The only people missing, though soon to arrive, were the main players from Central Casting: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

It was in these desolate surroundings that The Beatles hoped to get back to where they once belonged - back to the days when their music set in motion a chain reaction that altered western youth culture. A new year. A new hope. For the next couple of weeks at least, the studios would serve as their creative hub.

The premise was simple. The four most famous musicians in the world would be filmed writing and rehearsing new songs for a flyon-the-wall TV documentary. The pay-off would be their first proper live show since 29 August 1966, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco.

The prime mover, as he had been for the last two years, was McCartney, the Beatle-cheerleader-in-chief. The idea was that youd see The Beatles rehearsing, jamming, getting their act together and then finally performing somewhere in a big end-of-show concert, he recalled. Driven by a relentless work ethic, his enthusiasm for the group remained as full-on as ever. And so, it appeared, was the love held for them by fans who had been with them every inch of the way. Through early Beatlemania. Through the druggy mystery tour of the Summer of Love. Through the reinvented rock of The Beatles (aka theWhite Album).

Proof of their longevity lay in the fact that, as the decade entered its final year, The Beatles still sat imperiously at the top of the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic. The White Album, a four-sided record, had, despite its difficult birth, been hailed as an amalgam of pop, rock, country and soulful blues. But six years of unparalleled and dazzling success, combined with the relentless vagaries of fame, had taken an inevitable toll on relationships within the band.

Memories of the marathon sessions for the album, which was released in November 1968, were still fresh. The price for creating the music had been frayed nerves, angry bust-ups and, in the case of Starr, a week-long walkout.

By the turn of the year, McCartney, more than any of them, worried that the band was on life support, but he was not prepared to be the one to administer the last rites. He remained in denial over the serious disconnect that now existed between each of them. The cure, he was convinced, lay in a back-to-basics approach, the four of them creating great music in the studio and then going back on the road. Or at least playing a one-off gig to prove they could still cut it as a live band. He was even considering a surprise rocknroll-style drop-in, drop-out tour of northern dance halls. That was the fantasy he sold, and it was persuasive enough for them all to hook up at Twickenham on the second day of the year to begin sessions for a project tentatively and wistfully dubbed Get Back.

They were, of course, no longer the four callow kids who first stepped onto the worlds stage in 1963. Lennon had found Yoko Ono, the Japanese avant-garde artist seven years his senior for whom he broke up his marriage and with whom he dabbled in heroin. Harrison, having discovered a new inner confidence through Indian mysticism, was on a quest for Krishna consciousness. McCartney was enjoying the fame and acclaim that was his hearts desire. And Starr, whose childhood had been wrecked by illness, simply couldnt believe his luck at such a reversal of fortune.

But the symbiosis that once touched on telepathy had been replaced by lethargy. And now here they were, two days in to a new year, in a freezing studio they didnt know, hemmed in and tapped out and working once again under an autocratic conductor: McCartney.

As she had been during the White Album sessions, Yoko remained umbilically attached to Lennon, an awkward situation which acted like dry tinder. Harrison simply wanted to be somewhere anywhere else; Starr had a ringside seat at the long goodbye. It was far too soon after the fractious atmosphere of the White Album to get back to the future, but no one had the courage to say out loud what needed to be said.

Lennon recalled: Paul had this idea that we were going to rehearse or... see, it all was more like Simon and Garfunkel, like looking for perfection all the time. And so he has these ideas that well rehearse and then make the album. And of course were lazy fuckers and weve been playing for twenty years, for fucks sake, were grown men, were not going to sit around rehearsing. Im not, anyway. And we couldnt get into it. And we put down a few tracks and nobody was in to it at all.

It was a dreadful, dreadful feeling in Twickenham Studio, and being filmed all the time. I just wanted them to go away, and wed be there, eight in the morning. You couldnt make music at eight in the morning or ten or whatever it was, in a strange place with people filming you and coloured lights.

Lennons heart may not have been in it right from the start but he, like all of them, had initially appeared to buy in to the Get Back project, the seed for which had been planted after their first appearance before a live audience for two years. That had been at Twickenham, too: they had showcased Hey Jude and Lennons Revolution before the cameras for