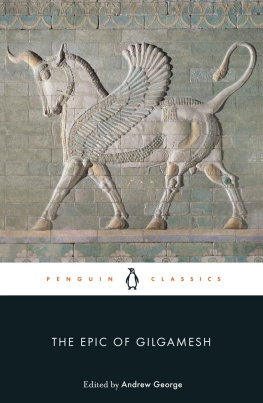

The Epic of Gilgamish

A new translation from a collation of the

cuneiform tablets in the British Museum

rendered literally into English hexameters

By

R. CAMPBELL THOMPSON

M.A., D. Litt., F.S.A., Fellow of Merton College, Oxford. LUZAC & CO., 46 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C.1.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1928

TO

COLONEL W. H. BEACH, C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O., R.E.,

UNDER WHOM I SERVED FOR THREE YEARS IN MESOPOTAMIA,

WHO BEST KNEW HOW TO ASSESS THE WORTH OF ORIENTAL STORIES

David De Angelis 2017 all rights reserved

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

THE Epic of Gilgamish, written in cuneiform on Assyrian and Babylonian clay tablets, is one of the most interesting poems in the world. It is of great antiquity, and, inasmuch as a fragment of a Sumerian Deluge text is extant, it would appear to have had its origin with the Sumerians at a remote period, perhaps the fourth millennium, or even earlier. Three tablets of it exist written in Semitic (Akkadian), which cannot be much later than 2,000 B.C.: half a millennium later come the remains of editions from Boghaz Keui, the Hittite capital in the heart of Asia Minor, written not only in Akkadian, but also in Hittite and another dialect. After these comes the tablet found at Ashur, the old Assyrian capital, which is anterior in date to the great editions now preserved in the British Museum, which were made in the seventh century B.C., for the Royal Library at Nineveh, one Sin-liqi-unni(n)ni being one of the editors. Finally there are small neo-Babylonian fragments representing still later editions.

In the seventh century edition, which forms the main base of our knowledge of the poem, it was divided into twelve tablets, each containing about three hundred lines in metre. Its subject was the Legend of Gilgamish, a composite story made up probably of different myths which had grown up at various times round the hero's name. He was one of the earliest Kings of Erech in the South of Babylonia, and his name is found written on a tablet giving the rulers of Erech, following in order after that of Tammuz (the god of vegetation and one of the husbands of Ishtar) who in his turn follows Lugalbanda, the tutelary god of the House of Gilgamish. The mother of Gilgamish was Nin-sun. According to the Epic, long ago in the old days of Babylonia (perhaps 5,000 B.C.), when all the cities had their own kings, and each state rose and fell according to the ability of its ruler, Gilgamish is holding Erech in thrall, and the inhabitants appeal to the Gods to be relieved from his tyranny. To aid them the wild man Enkidu is created, and he, seduced by the wiles of one of the dancing girls of the Temple of Ishtar, is enticed into the great city, where at once (it would appear) by ancient right Gilgamish attempts to rob him of his love. A tremendous fight ensues, and mutual admiration of each other's prowess follows, to so great an extent that the two heroes become firm friends, and determine to make an expedition together to the Forest of Cedars which is guarded by an Ogre, Humbaba, to carry off the cedar wood for the adornment of the city. They encounter Humbaba, and by the help of the Sun-god who sends the winds to their aid, capture him and cut off his head; and then, with this exploit, the goddess Ishtar, letting her eye rest on the handsome Gilgamish, falls in love with him. But he rebuffs her proposal to wed him with contumely, and she, indignant at the insult, begs her father Anu to make a divine bull to destroy the two heroes. This bull, capable of killing three hundred men at one blast of his fiery breath, is overcome by Enkidu, who thus incurs the punishment of hybris at the hands of the gods, who decide that, although Gilgamish may be spared, Enkidu must die. With the death of his friend, Gilgamish in horror at the thought of similar extinction goes in search of eternal life, and after much adventuring, meets first with Siduri, a goddess who makes wine, whose philosophy of life, as she

gives it him, however sensible, is evidently intended to smack of the hedonism of the bacchante. Then he meets with Ur-Shanabi (the boatman of Uta-Napishtim) who may perhaps have been introduced as a second philosopher to give his advice to the hero, which is now lost; conceivably he has been brought into the story because of the sails(?) which would have carried them over the waters of Death (by means of the winds, the Breath of Life?), if Gilgamish had not previously destroyed them with his own hand. Finally comes the meeting with Uta-Napishtim (Noah) who tells Gilgamish the story of the Flood, and how the gods gave him, the one man saved, the gift of eternal life. But who can do this for Gilgamish, who is so human as to be overcome by sleep? No, all UtaNapishtim can do is to tell him of a plant at the bottom of the sea which will make him young again, and to obtain this plant Gilgamish, tying stones on his feet in the manner of Bahrein pearl-divers, dives into the water. Successful, he sets off home with his plant, but, while he is washing at a chance pool, a snake snatches it from him, and he is again frustrated of his quest, and nothing now is left him save to seek a way of summoning Enkidu back from Hades, which he tries to do by transgressing every tabu known to those who mourn for the dead. Ultimately, at the bidding of the God of the Underworld Enkidu comes forth and pictures the sad fate of the dead in the Underworld to his friend: and on this sombre note the tragedy ends.

Of the poetic beauty of the Epic there is no need to speak. Expressed in a language which has perhaps the simplicity, not devoid of cumbrousness, of Hebrew rather than the flexibility of Greek, it can nevertheless describe the whole range of human emotions in the aptest language, from the love of a mother for her son to the fear of death in the primitive mind of one who has just seen his friend die; or from the anger of a woman scorned to the humour of an editor laughing in his sleeve at the ignorance of a savage. Whether there is justification for taking the risk of turning it into ponderous English hexameter metre is an open question, but in so doing I have done my utmost to preserve an absolutely literal translation, duly enclosing in a round bracket, (), every amplification of the original phrasing which either sense or metre or particularly an appreciation of unproven Assyrian particles has demanded. Restorations, either probable from the context or certain from parallels, have been enclosed in square brackets [].

To George Smith, one of the greatest geniuses Assyriology has produced, science owes much for the first arrangement and translations of the text of this extraordinary poem: indeed, it was for this Epic that he sacrificed his life, for actually it was the discovery of the Deluge Tablet in the British Museum Collections which led the Daily Telegraph to subscribe so generously for the re-opening of the diggings in the hope of further finds at

Kouyunjik (Nineveh), in conducting which he died all too early in 1876. Sir Henry Rawlinson and Professor Pinches played no small part in the reconstruction and publication of at least two of the tablets, and to their labours in this field must be added the ingenuity of Professor Sayce, and the solid acumen of Dr. L. W King. In America to Professor Haupt is owed the first complete edition of the texts, very accurately copied, and later on the editions of two early Babylonian texts were edited by Langdon, Clay and Jastrow: among German publications must be mentioned the translations of Jensen and Ungnad, with the edition of an Old Babylonian tablet by Meissner. The Boghaz Keui texts have been edited by Weidner, Friedrich, and Ungnad. It would be superfluous to say how much I am indebted to the labours of all these scholars.

The present version is based on a fresh collation of the original tablets in the British Museum, the results of which I propose to publish shortly in a critical edition of both text and translation. It will be seen that I have departed from the accepted order of several of the fragments of which the position in the Epic is problematical. An examination of numerous fragments of tablets of a religious nature has naturally led to the discovery of duplicates and joins, some of which will be apparent in the present text. For their great liberality in granting me facilities to copy and collate these valuable tablets I have to express my heartiest thanks to the Trustees of the British Museum, and the Director, Sir Frederick Kenyon. To my friends Dr. H. R. Hall, and Messrs. Sidney Smith and C. J. Gadd of the British Museum, I am greatly indebted for much help in forwarding the work: and to Sir John Miles, Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, I owe many shrewd suggestions.

Next page