13 JANUARY 2005, NEW YORK

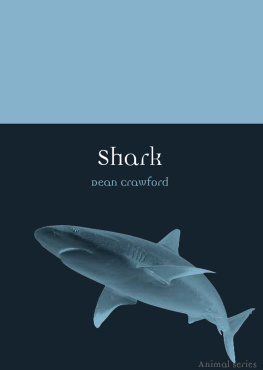

O NE PROBLEM FOR the agent trying to sell the stuffed shark was the $12 million asking price for this work of contemporary art. Another was that it weighed just over 2 tons, and was not going to be easy to carry home. The taxidermy 15-foot tiger shark sculpture was mounted in a giant glass vitrine and creatively named The PhysicalImpossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. It is illustrated in the centre portion of the book. The shark had been caught in 1991 in Australia, and prepared and mounted in England by technicians working under the direction of British artist Damien Hirst.

Another concern was that while the shark was certainly a novel artistic concept, many in the art world were uncertain as to whether it qualified as art. The question was important because $12 million represented more money than had ever been paid for a work by a living artist, other than Jasper Johns more than for a Gerhard Richter, a Robert Rauschenberg or a Lucian Freud.

Why would anyone even consider paying this much money for the shark? Part of the answer is that in the world of contemporary art, branding can substitute for critical judgement, and lots of branding was involved here. The seller was Charles Saatchi, an advertising magnate and famous art collector, who fourteen years earlier had commissioned Hirst to produce the work for 50,000. At the time that sum was considered so ridiculous that the Sun heralded the transaction with the headline 50,000 For Fish Without Chips. Hirst intended the figure to be an outrageous price, set as much for the publicity it would attract as for the monetary return.

The agent selling the shark was New York-based Larry Gagosian, the worlds most famous art dealer. One buyer known to be actively pursuing the shark was Sir Nicholas Serota, director of Londons Tate Modern museum, who had a very constrained budget to work with. Four collectors with much greater financial means had shown moderate interest. The most promising was American Steve Cohen, a very rich Connecticut hedge-fund executive. Hirst, Saatchi, Gagosian, Tate, Serota and Cohen represented more art world branding than is almost ever found in one place. Saatchis ownership and display of the shark had become a symbol for newspaper writers of the shock art being produced by the group known as the Young British Artists, the yBas. Put the branding and the publicity together and the shark must be art, and the price must not be unreasonable.

There was another concern, serious enough that with any other purchase it might have deterred buyers. The shark had deteriorated dramatically since it was first unveiled at Saatchis private gallery in London in 1992. Because the techniques used to preserve it had been inadequate, the original had decomposed until its skin became heavily wrinkled and turned a pale green, a fin had fallen off, and the formaldehyde solution in the tank had turned murky. The intended illusion had been of a tiger shark swimming towards the viewer through the white space of the gallery, hunting for dinner. The illusion now was described as entering Norman Bates fruit cellar and finding Mother embalmed in her chair. Curators at the Saatchi Gallery tried adding bleach to the formaldehyde, but this only hastened the decay. In 1993 the curators gave up and had the shark skinned. The skin was then stretched over a weighted fibreglass mould. The shark was still greenish, still wrinkled.

Damien Hirst had not actually caught the now-decaying shark. Instead he made Shark Wanted telephone calls to post offices on the Australian coast, which put up posters giving his London number. He paid 6,000 for the shark: 4,000 to catch it and 2,000 to pack it in ice and ship it to London. There was the question of whether Hirst could replace this rotting shark simply by purchasing and stuffing a new one. Many art historians would argue that if refurbished or replaced, the shark became a different artwork. If you overpainted a Renoir, it would not be the same work. But if the shark was a conceptual piece, would catching an equally fierce shark and replacing the original using the same name be acceptable? Dealer Larry Gagosian drew a weak analogy to American installation artist Dan Flavin, who works with fluorescent light tubes. If a tube on a Flavin sculpture burns out, you replace it. Charles Saatchi, when asked if refurbishing the shark would rob it of its meaning as art, responded Completely. So what is more important the original artwork or the artists intention?

Nicholas Serota offered Gagosian $2 million on behalf of Tate Modern, but it was turned down. Gagosian continued his sales calls. When alerted that Saatchi intended to sell soon, Cohen agreed to buy.

Hirst, Saatchi and Gagosian are profiled later in the book. But who is Steve Cohen? Who pays $12 million for a decaying shark? Cohen is an example of the financial-sector buyer who drives the market in high-end contemporary art. He is the owner of SAC Capital Advisors in Greenwich, Connecticut, and is considered a genius. He manages $11 billion in assets and is said to earn $500 million a year. He displays his trophy art in a 32,000sq ft mansion in Greenwich, a 6,000sq ft pied--terre in Manhattan, and a 19,000sq ft bungalow in Delray Beach, Florida. In 2007 he purchased a ten-bedroom, 2-acre estate in East Hampton, New York.

To put the $12 million price tag in context it is necessary to understand how rich really rich is. Assume Mr Cohen has a net worth of $4 billion to go with an annual income of $500 million before tax. Even at a 10 per cent rate of return far less than he actually earns on the assets he manages his total income is just over $16 million a week, or $90,000 an hour. The shark cost him five days income.

Some journalists later expressed doubt as to whether the selling price for Physical Impossibility actually was $12 million. Several New York media reported that the only other firm offer aside from that made by Tate Modern came from Cohen, and the actual selling price was $8 million. New YorkMagazine reported $13 million. But the $12 million figure was the most widely cited, it produced extensive publicity, and the parties agreed not to discuss the amount. At any of these numbers, the sale greatly increased the value of the other Hirst works in the Saatchi collection.

Cohen was not sure what to do with the shark; it remained stored in England. He said he might donate it to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York which might have led to his being offered a position on the MoMA board. The art world heralded the purchase as a victory for MoMA over Londons Tate Modern. The Guardian bemoaned the sale to an American, saying The acquisition will confirm MoMAs dominance as the leading gallery of modern art in the world.

I began the journey of discovery that became this book at the Royal Academy of Arts in London where on 5 October 2006, along with 600 others, I attended a private preview of USA Today, an exhibition curated by the same Charles Saatchi. This was billed as an exhibition of art by thirty-seven talented young American artists. Many were not in fact American-born, though they were working in New York an illustration of how hard it is to label an artist.

The Royal Academy (RA) is a major British public gallery. Founded in 1768, it promotes its exhibitions as comparable to those at the National Gallery, the two Tate galleries, and leading museums outside the UK. The USAToday show was not a commercial art fair, because nothing was listed as for sale. Nor was it a traditional museum show, because one man, Charles Saatchi, owned all the work. He chose what was shown. The work would appreciate in value from being shown in such a prestigious public space, and all profit from future sales would accrue to Saatchi.