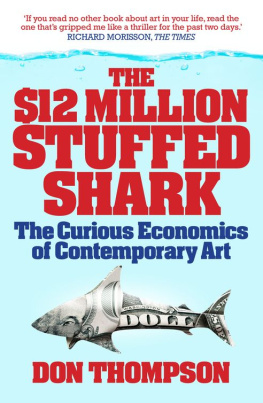

THE $12

MILLION

STUFFED

SHARK

THE CURIOUS

ECONOMICS OF

CONTEMPORARY ART

Don Thompson

THE $12 MILLION STUFFED SHARK

Copyright Don Thompson, 2008.

All rights reserved.

First published 2008 by Aurum Press Ltd, London, UK

First Published in the United States in 2008 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLANa division of St. Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

ISBN-13: 978-0-230-61022-4

ISBN-10: 0-230-61022-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thompson, Donald N.

The $12 million stuffed shark : the curious economics of contemporary art / Donald N. Thompson.

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-230-61022-6

1. Art, Modern20th centuryEconomic aspects. 2. Art, Modern21st centuryEconomic aspects. 3. ArtMarketingHistory20th century. 4. ArtMarketingHistory21st century. 5. ArtCollectors and collecting Psychological aspects. I. Title: Twelve million dollar stuffed shark. II. Title.

N6490.T525 2008

709.049dc22

2008017980

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre, Inc.

First Palgrave Macmillan edition: September 2008

Printed in the United States of America.

CONTENTS THE $12 MILLION STUFFED SHARK

JANUARY 13, 2005,

NEW YORK

One problem for the agent trying to sell the stuffed shark was the $12 million asking price for this work of contemporary art. Another was that it weighed just over two tons, and was not going to be easy to carry home. The taxidermy fifteen-foot tiger shark sculpture was mounted in a giant glass vitrine and creatively named The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. It is illustrated in the center portion of the book. The shark had been caught in 1991 in Australia, and prepared and mounted in England by technicians working under the direction of British artist Damien Hirst.

Another concern was that while the shark was certainly a novel artistic concept, many in the art world were uncertain whether it qualified as art. The question was important because $12 million represented more money than had ever been paid for a work by a living artist, other than Jasper Johnsmore than for a Gerhard Richter, a Robert Rauschenberg, or a Lucian Freud.

Why would anyone even consider paying this much money for the shark? Part of the answer is that in the world of contemporary art, branding can substitute for critical judgment, and lots of branding was involved here. The seller was Charles Saatchi, an advertising magnate and famous art collector, who fourteen years earlier had commissioned Hirst to produce the work for 50,000. At the time that sum was considered so ridiculous that The Sun heralded the transaction with the headline 50,000 For Fish Without Chips. Hirst intended the figure to be an outrageous price, set as much for the publicity it would attract as for the monetary return.

The agent selling the shark was New York-based Larry Gagosian, the worlds most famous art dealer. One buyer known to be actively pursuing the shark was Sir Nicholas Serota, director of Londons Tate Modern museum, who had a very constrained budget to work with. Four collectors with much greater financial means had shown moderate interest. The most promising was American Steve Cohen, a very rich Connecticut hedge fund executive. Hirst, Saatchi, Gagosian, Tate, Serota, and Cohen represented more art world branding than is almost ever found in one place. Saatchis ownership and display of the shark had become a symbol for newspaper writers of the shock art being produced by the group known as the Young British Artists, the yBas. Put the branding and the publicity together and the shark must be art, and the price must not be unreasonable.

There was another concern, serious enough that with any other purchase it might have deterred buyers. The shark had deteriorated dramatically since it was first unveiled at Saatchis private gallery in London in 1992. Because the techniques used to preserve it had been inadequate, the original had decomposed until its skin became heavily wrinkled and turned a pale green, a fin had fallen off, and the formaldehyde solution in the tank had turned murky. The intended illusion had been of a tiger shark swimming toward the viewer through the white space of the gallery, hunting for dinner. The illusion now was described as entering Norman Bates fruit cellar and finding Mother embalmed in her chair. Curators at the Saatchi Gallery tried adding bleach to the formaldehyde, but this only hastened the decay. In 1993 the curators gave up and had the shark skinned. The skin was then stretched over a weighted fiberglass mold. The shark was still greenish, still wrinkled.

Damien Hirst had not actually caught the now-decaying shark. Instead he made Shark Wanted telephone calls to post offices on the Australian coast, which put up posters giving his London number. He paid 6,000 for the shark: 4,000 to catch it and 2,000 to pack it in ice and ship it to London. There was the question of whether Hirst could replace this rotting shark simply by purchasing and stuffing a new one. Many art historians would argue that if refurbished or replaced, the shark became a different artwork. If you overpainted a Renoir, it would not be the same work. But if the shark was a conceptual piece, would catching an equally fierce shark and replacing the original using the same name be acceptable? Dealer Larry Gagosian drew a weak analogy to American installation artist Dan Flavin, who works with fluorescent light tubes. If a tube on a Flavin sculpture burns out, you replace it. Charles Saatchi, when asked if refurbishing the shark would rob it of its meaning as art, responded Completely. So what is more importantthe original artwork or the artists intention?

Nicolas Serota offered Gagosian $2 million on behalf of Tate Modern, but it was turned down. Gagosian continued his sales calls. When alerted that Saatchi intended to sell soon, Cohen agreed to buy.

Hirst, Saatchi, and Gagosian are profiled later in the book. But who is Steve Cohen? Who pays $12 million for a decaying shark? Cohen is an example of the financial-sector buyer who drives the market in high-end contemporary art. He is the owner of SAC. Capital Advisors, LLC in Greenwich, Connecticut, and is considered a genius. He manages $11 billion in assets and is said to earn $500 million a year. He displays his trophy art in a 32,000 square foot mansion in Greenwich, a 6,000 square foot pied--terre in Manhattan, and a 19,000 square foot bungalow in Delray Beach, Florida. In 2007 he purchased a ten bedroom, two acre estate in East Hampton, New York.

To put the $12 million price tag in context it is necessary to understand how rich really rich is. Assume Mr Cohen has a net worth of $4 billion to go with an annual income of $500 million before tax. At a 10 percent rate of returnfar less than he actually earns on the assets he manageshis total income is just over $16 million a week, or $90,000 an hour. The shark cost him five days income.

Some journalists later expressed doubt whether the selling price for Physical Impossibility actually was $12 million. Several New York media reported that the only other firm offer aside from that made by Tate Modern came from Cohen, and the actual selling price was $8 million. New York Magazine reported $13 million. But the $12 million figure was the most widely cited, it produced extensive publicity, and the parties agreed not to discuss the amount. At any of these numbers, the sale greatly increased the value of the other Hirst work in the Saatchi collection.

Next page