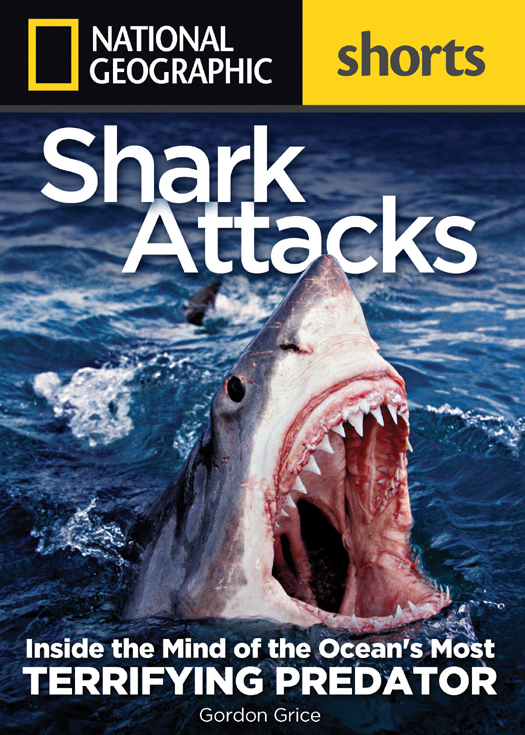

Published by the National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036

Copyright 2012 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

eISBN: 978-1-4262-0981-9

Cover photo by Brandon Cole

The National Geographic Society is one of the worlds largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to increase and diffuse geographic knowledge, the Societys mission is to inspire people to care about the planet. It reaches more than 400 million people worldwide each month through its official journal, National Geographic, and other magazines; National Geographic Channel; television documentaries; music; radio; films; books; DVDs; maps; exhibitions; live events; school publishing programs; interactive media; and merchandise. National Geographic has funded more than 10,000 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting geographic literacy.

For more information, visit www.nationalgeographic.com

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

v3.1

C ONTENTS

C HAPTER 1

Swallowed Whole

C HAPTER 2

Shark Sense

C HAPTER 3

Scent Trails

C HAPTER 4

A Voracious Appetite

C HAPTER 5

Deadly Soup

C HAPTER 6

Dont Look at It

C HAPTER 7

Law of the Food Chain

C HAPTER 8

Apex Predators

A 14-foot great white shark swims purposefully, hunting prey at the surface of tranquil blue waters near Gansbaai, South Africa.

(David Doubilet/National Geographic Stock)

C HAPTER 1

Swallowed Whole

T he afternoon he was swallowed whole, Bob Pamperin was hunting abalone. An abalone is a sort of large sea snail. It lives in a humped shell like a turtles, and it eats by whipping its toothy tongue across the fur of fine algae clinging to rocks. You can eat abalone braised with mushrooms or Chinese cabbage. You can pan-fry them or bake them with sliced avocadoes.

If gathering food had been the only goal, Pamperin and his friend Gerald Lehrer could have gone groping under the rocks of Alligator Head. The area, at the western extremity of La Jolla Cove in San Diego County, California, is picturesque, with outcroppings and islets and caverns wide enough to kayak through. But on this evening in June 1959, shortly after five oclock, with the temperature at 68 degrees and the water lucid, Pamperin and Lehrer were in it for the sport, so they were free diving. In six or seven fathoms of water, theyd collect the abalone and return with them to the surface, where theyd left an inner tube floating. A burlap bag attached to the inner tube held the catch.

The men had separated by at least 30 feet when Lehrer heard Pamperin say, Help me. He saw Pamperin jutting from the waterstanding in it, but too high. Lehrer thought his friend might have a cramp, so he swam toward him. And then he noticed the water was red. Pamperin was sinking into it. Looking down on the water from a rock formation, one witness saw Pamperin thrashing as if he were trying to run away from something. Then Pamperin vanished.

Lehrer dived to find him. There was a good 20 feet of visibility that day, and he saw his friend protruding from the mouth of a shark, his legs already engulfed. After surfacing for a breath, Lehrer dived down to help. By this time, the shark was lying on the sandy bottom, thrashing side to side. Lehrer couldnt decide whether it was trying to swallow its victim or spit him out. He surfaced for another breath, then dived again, waving his arms to scare the shark.

It didnt work. The animal seemed not even to notice him. It went on with its swallowing. Helpless, Lehrer swam for shore.

Within the hour, divers were in the water searching. The pilot of a helicopter surveying the area spotted a blue swim fin, which was the right color to have been Pamperins. A few hours later, the inner tube drifted in at the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club. Two abalone were still in the burlap bag.

Authorities showed Lehrer pictures of different shark species, and he recognized the attacker as a great white. Record specimens for this species are roughly 20 feet long and weigh over 7,000 pounds. One large individual measured more than 32 inches across the jawsa smile broader than a refrigerator. By Lehrers estimate, the shark that took Pamperin may have been bigger than that.

For a shark, the water that evening was rife with hints of food. Harbor seals congregated at a rookery 600 yards from the attack site. A man diving from the rocks at Alligator Head had hurt himself and bled copiously into the water. Other divers had speared some yellowtail amberjacks. Perhaps most important, according to shark expert Ralph S. Collier, a whales carcass had washed up at La Jolla Shores the night before, about 900 yards from the site of the attack. The redolent oil and blood of it may have drawn the predator in a feeding mood.

C HAPTER 2

Shark Sense

A sharks sense of smell is famously powerful, allowing some hunting sharks to detect fish oil at concentrations lower than one part per ten billion parts of ocean water. The nostrils of a shark have nothing to do with breathing. They are separate organs, connected most prominently to the massive olfactory lobe of the brain. A shark moves its head side to side as it swims, allowing it to detect the direction of scent trails. In pursuit of an interesting hint, a shark will swim in a search pattern, carving large Ss in the water until it gets a strong fix on a smell. The oceanic whitetip, notorious for its habit of showing up at shipwrecks, is even said to poke its head out of water to sniff for airborne scents.

A whale carcass adrift trails scent. Surfer George Greenough writes that in an area where he usually has one encounter with a big shark per year, a whale carcass brought him half a dozen in half a year. It was 2007, and a small whale came drifting into Byron Bay, Australia. It was being hammered by sharks, says Greenough. The sharks themselves helped create a stronger trail for other sharks with their sloppy eating. The carcass eventually beached and was hauled away. Although the whale was gone, Greenough writes, the sharks were not. There was now a chum trail that ended at Byron Bay.

In his encounters that year, Greenough made eye contact with one great white and was pursued by another. There was a great white two feet across, and another encounter with a shark that showed nothing but a foot of dorsal fin above water and a tail six feet behind it. In one case, Greenough, surfing in dirty water, stopped paddling and glided forward a few feet. At the place where hed stopped kicking, a patch of water at least four feet across boiled up with an audible rush. He couldnt see more than 18 inches into the water, but he saw a trail of telltale swirls moving toward the beach, perhaps looking for him.