INTRODUCTION

B UT WHY CANT WE GO LOOK AT IT ? I asked my mother.

Because its dangerous, she said.

We could watch from the car.

Well go back into town and let Granddad handle it.

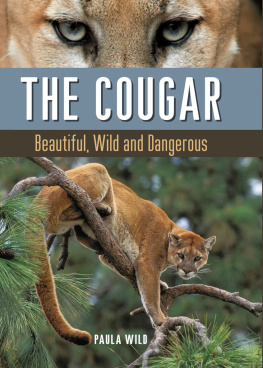

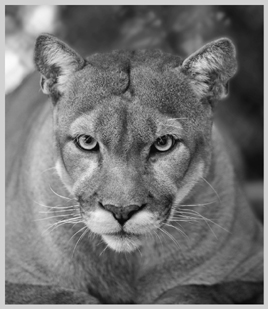

We never get to do anything fun, I said, but the argument was lost already, the red cedar fence posts clicking by faster and faster outside the car window. I picked at the threads in the green upholstery of the backseat. Mom was putting miles of safety between us and the cougar treed in front of our farmhouse. My grandfather had waved us down as we drove home from errands and told us to proceed no farther. I was six; it didnt occur to me to worry about my grandfather. I only knew I was missing out on something.

The next time I saw him, Granddad was the same as always, tossing his silver head as he told his jokes, smiling in his broad but mysterious way, like the man on the Quaker Oats box. He had little to say about the fate of the cougar. Only with the distance of years do I understand what must have passed among the adults of my family, how they must have felt to see a predator like that in the elm tree my sister and I played beneath each day.

We lived in the Oklahoma Panhandle, where the soil was black as coffee and could be coaxed to grow anything if only you could pipe enough water to it. It was a land of extremes, of tornadoes and droughts and dust storms, and the sense of history I absorbed from my family was centered on the apocalypse of the Dust Bowl. It was a land where things that ought to seem strange happened as a matter of course. One clear summer afternoon, we felt a rumble low in our bones, and then the house seemed to quiver like a drop of water thinking of falling. It was over in a second.

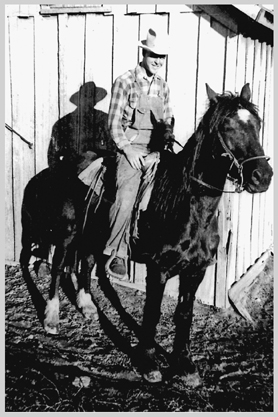

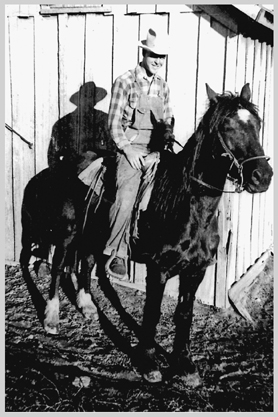

MY GRANDFATHER ON HIS HORSE, OLE CHARGER.

Earthquake! my sister Meg and I shouted as one. Mom was dubious; whatever it was had made a sound, and the sound had seemed to come from the corral. Granddad sipped his tea calmly. Meg and I tore out to the corral, shouting back to Mom that we promised to be careful.

Near the cattle tank we came upon a smoking scatter of stones, clearly the breakings of a single rock. The original mass must have been bigger than a basketball.

Volcano rocks! I said.

But wheres the volcano? Meg said. We looked all around us. The horizon was flat in every direction. There were no peaks, nothing that might have passed for a volcano, even with imagination. We came speeding back into the house to report our findings.

It must be a meteor, Granddad explained. It was a new idea for us.

Dont touch it, Mom said. Its probably still hot.

The pieces looked different after they cooledsmooth green wedges, like slabs cut from mint ice cream. They were heavier than they looked, heavier in fact than any rock Id ever hefted. Meg and I used them when we played Star Trek; they were moon stones, valuable ore, some transmutative substance. Meg came home from school with a set of terminologymeteor, meteoroid, meteoritethat she drilled into me, and when we next saw our cousins, we all went out to watch for meteorites and make fun of people who called them falling stars. And we went on with our lives as if nothing much had happened.

But the Panhandle oddities that interested me most were biological: a two-headed Hereford calf at the local museum, plagues of grasshoppers and rabbits, mastodons dug out of the fields, the tracks of allosaurs found in stone. Carnivals came through, displaying five-legged sheep and three-legged hens and, once, a pickled two-headed human baby. One summer when I was ten, prodigious congregations of black crickets rose from the soil. They seethed beneath the outdoor lights. Once they came pouring over the edge of our front porch, where a friend and I had just squashed a grasshopper. It seemed, for a panicky moment, like retribution.

Only as I write this do I realize how forbidding the Panhandle must seem to outsiders. To us, it was home. My fathers family had lived there since 1904, which was virtually as long as cattle and railroads had been there in place of bison and mustang herds. The lives of my ancestors were riddled with ghost towns and vanished homesteads, but here they had made the earth yield. All of my grandparents were farmers, and that occupation was understood to call for a kind of integrity others couldnt muster.

But we were a family falling away from the land. My mother would have been happier in town. My father liked the country, but not the life of a farmer. By the time I was a teen, he owned a fleet of tow trucks, and my mother held an office job. Theyd become townies. I still spent a lot of time in the country with kinsmen and friends, but Id lost something. I never got it back.

T HE REAL COUGAR passed from my life permanently. I never even glimpsed him. But the memory of him was written in fire. It seemed a special cruelty for my elders to deny me his company, for I was already obsessed with wild animals and wanted to see him more than I can perhaps make clear. Already I had heard the voice of the bobcat and followed the delicate and sinuous track of the rattlesnake; soon I would begin to keep insects and spiders in jars; within a few years I would fill notebooks with my observations and drawings of wildlife. I have spent much of my adult life in the same pursuits.

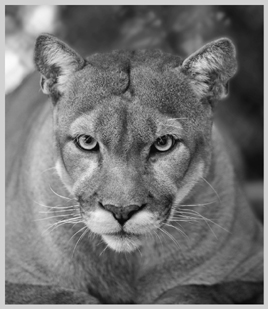

A COUGAR BEGINS BY OPENING THE BELLY.

It was decades before I encountered another cougar in the wild. As before, I never laid eyes on it. I had to use other senses to detect it. I came into the territory of this particular cougar by accident when friends invited me to spend a few days at a ranch in Wyoming.

My friends and I went out for a ride. Our horses shoes clapped against the steep granite as we worked our way around the mountains shoulder. Then we were into a stretch of open field. My horse, a big, unruly bay, trudged through a clattering pile of bones. I reined him in and asked Virgil, the wrangler, about the carcass. We dismounted.

Virgil handed me the skull. It was about as long as my hand, equipped with broad molars for chewing vegetation. The front of the mouth lacked teeth.

Pronghorn antelope, Virgil said, untying his ponytail to bind it tighter. They dont have front teeth. They use their lips to pull in grass and leaves. He used his own lips to hold the rubber band while he worked on his hair.

The horns themselves were gone. We looked the bones over to see if we could figure out what had killed the pronghorn. We found plenty of marks, but what to make of them?

These look like something chewed on them, I said, holding up a femur and an uncertain fragment.