The Book of Deadly Animals

GORDON GRICE

PENGUIN BOOKS

Previously published as Deadly Kingdom

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America as

Deadly Kingdom: The Book of Dangerous Animals by The Dial Press 2010

Revised edition published in Great Britain as The Book of Deadly Animals by Penguin Books Ltd 2011 Published by arrangement with The Dial Press, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

Published in Penguin Books (USA) 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright Gordon Grice, 2010

All rights reserved

Portions of this book originally appeared in Arkansas Literary Forum,

Discover, Granta, and Oklahoma Today in different form

Photo permission credits can be found beginning on .

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Grice, Gordon (Gordon D.)

[Deadly kingdom]

The book of deadly animlas / Gordon Grice.

p. cm.

Originally published under title: Deadly kingdom, New York : Dial Press, c.2010

Includes Index.

EISBN: 9781101572238

1. Dangerous animals. I. title.

QL100.G75 2012

591.6dc23 2011040892

Printed in the United States of America

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

For Tracy, Parker, Beckett, Griffin, and Abilene

Philosophy is really there to redeem what lies in an animals gaze.

Theodor Adorno

Introduction

But why cant we go look at it? I asked my mother.

Because its dangerous, she said.

We could watch from the car.

Well go back into town and let Granddad handle it.

We never get to do anything fun, I said, but the argument was lost already, the red cedar fence posts clicking by faster and faster outside the car window. I picked at the threads in the green upholstery of the backseat. Mom was putting miles of safety between us and the cougar treed in front of our farmhouse. My grandfather had waved us down as we drove home from errands and told us to proceed no farther. I was six; it didnt occur to me to worry about my grandfather. I only knew I was missing out on something.

The next time I saw him, Granddad was the same as always, tossing his silver head as he told his jokes, smiling in his broad but mysterious way, like the man on the Quaker Oats box. He had little to say about the fate of the cougar. Only with the distance of years do I understand what must have passed among the adults of my family, how they must have felt to see a predator like that in the elm tree my sister and I played beneath each day.

We lived in the Oklahoma Panhandle, where the soil was black as coffee and could be coaxed to grow anything if only you could pipe enough water to it. It was a land of extremes, of tornadoes and droughts and dust storms, and the sense of history I absorbed from my family was centered on the apocalypse of the Dust Bow. It was a land where things that ought to seem strange happened as a matter of course. One clear summer afternoon, we felt a rumble low in our bones, and then the house seemed to quiver like a drop of water thinking of falling. It was over in a second.

Earthquake! my sister Meg and I shouted as one. Mom was dubious; whatever it was had made a sound, and the sound had seemed to come from the corral. Granddad sipped his tea calmly. Meg and I tore out to the corral, shouting back to Mom that we promised to be careful.

Near the cattle tank we came upon a smoking scatter of stones, clearly the breakings of a single rock. The original mass must have been bigger than a basketball.

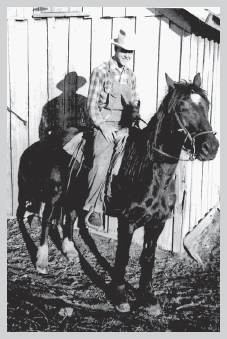

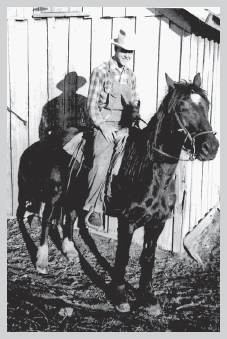

My grandfather on his horse, Ole Charger.

Volcano rocks! I said.

But wheres the volcano? Meg said. We looked all around us. The horizon was flat in every direction. There were no peaks, nothing that might have passed for a volcano, even with imagination. We came speeding back into the house to report our findings.

It must be a meteor, Granddad explained. It was a new idea for us.

Dont touch it, Mom said. Its probably still hot.

The pieces looked different after they cooled smooth green wedges, like slabs cut from mint ice cream. They were heavier than they looked, heavier in fact than any rock Id ever hefted. Meg and I used them when we played Star Trek; they were moon stones, valuable ore, some transmutative substance. Meg came home from school with a set of terminology meteor, meteoroid, meteorite that she drilled into me, and when we next saw our cousins, we all went out to watch for meteorites and make fun of people who called them falling stars. And we went on with our lives as if nothing much had happened.

But the Panhandle oddities that interested me most were biological: a two-headed Hereford calf at the local museum, plagues of grasshoppers and rabbits, mastodons dug out of the fields, the tracks of allosaurs found in stone. Carnivals came through, displaying five-legged sheep and three-legged hens and, once, a pickled two-headed human baby. One summer when I was ten, prodigious congregations of black crickets rose from the soil. They seethed beneath the outdoor lights. Once they came pouring over the edge of our front porch, where a friend and I had just squashed a grasshopper. It seemed, for a panicky moment, like retribution.

Only as I write this do I realize how forbidding the Panhandle must seem to outsiders. To us, it was home. My fathers family had lived there since 1904, which was virtually as long as cattle and railroads had been there in place of bison and mustang herds. The lives of my ancestors were riddled with ghost towns and vanished homesteads, but here they had made the earth yield. All of my grandparents were farmers, and that occupation was understood to call for a kind of integrity others couldnt muster.