Anyone can kill a deer. It takes a real man

to kill a varmint.

BEN LILLY , The Ben Lilly Legend

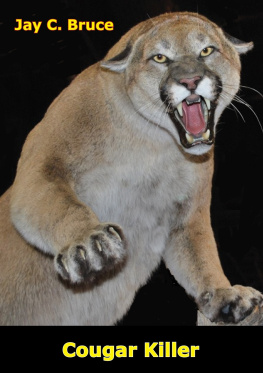

F or most cougar hunters, the challenge of outsmarting a large predator and the thrill of the chase were far more rewarding than the payment earned. Near the end of his 194 8 b ook Hunting American Lions , Frank C. Hibben described the cougar as a fascinating, terrifying, and sometimes loveable cat. He should know: in the mid-1930s he spent a couple of years chasing them through the rugged canyon country of New Mexico conducting research for the Southwestern Conservation League. Hibben wrote about his experiences in a vivid style that made the reader feel as if they were part of the hunt, sharing the excitement and chaos right alongside him.

We had scarcely reached the edge of the cliff when we saw the lion. Old Crook was in the face of the beast and both of them were on a narrow jutting ledge that reached out over the depths of the Gila Canyon with a sheer drop of a thousand feet below them. First one and then another of the other hounds reached the little rocky point where the cougar had come to bay. The pinnacles and rough-edged cliffs echoed a roar of sound which united in a crescendo of furious howls, barks and yelps that would have done credit to a volcanic eruption of major proportions.

I think Homer and I too were yelling as we scrambled down over the rocks and ledges with our chaps flying and loose rocks and fragments rolling from beneath our feet. But any sound of exhilaration which we might have made was completely lost in the roar of the dogs as they faced the snarling lion...

So furious was the onslaught of noise and confusion that the cat had backed to the narrow edge of the cliff so that his tail and hind quarters hung over the shadows of the empty gorge below. A wisp of blood-flecked foam dripped from those cat jaws and whipped away in the wind. The ears of the beast were laid back flat against his head and the lips of his muzzle were curled up straight to reveal every white, gleaming fang down to its yellow base.

As the dogs crowded one another close, the lion unsheathed its claws and struck with a sidewise motion so quick that the movement was blurred to the human eye. Those raking, curved claws barely missed a dog with each strike, but still they crowded closer. The hounds behind pushed the ones in front into the very jaws of destruction. The long sweeping curve of those needle-sharp claws, or the bite of those white canines, would find a mark in a matter of seconds. The dog or the lion or both could make a miss-step of only inches to plunge themselves into destruction on the rough lava rocks in the canyon below us.

... The dogs had pushed old Bugger almost between the front paws of the lion. The cougar struck again and again with lightening rapidity. I could see the fleck of red flesh that showed where Buggers shoulder had been torn by a claw. The dog caught himself with difficulty... and hung for a brief second on the very edge of the cliff scrambling for life.

... The great cat with the purchase of his hind paws barely on the edge of the rock cliff, leaped clear over the dog pack crowded in front of him. With two tremendous bounds he cleared the edge of the cliff and was running along a ledge just below us. The cat-like certainty and precision of that fleeing beast was amazing. A miscalculation of inches in any one of his great bounds would have meant certain death. The lion was running along the face of the cliff as though he had suction cups on those big round paws.

Although many cougar hunters experienced what Hibben called a fever in the blood when tracking a big cat, most werent chasing cougars for scientific purposes. As settlers increased the pressure to rid the country of large predators, the extermination of the noxious beasts began in earnest. A timeline on The Cougar Funds website states that, as early as 1684, Connecticut introduced a bounty on cougars. Over time, other states and provinces followed. Bounty hunters, and later government predator control agents, employed a variety of methods to kill the big cats, such as poison, trapping and tracking. But it wasnt easy. Cougars prefer fresh meat so poisoned bait didnt work on them nearly as well as it did on wolves. And pit and leg-hold traps, sometimes smeared with catnip and petroleum oil, werent very effective either. Eventually everyone agreed: the best way to catch a cat was to chase it with hounds, tree it, then shoot it.

Initially, many bounty hunters were farmers and ranchers looking for opportunities to supplement their income. But when they realized decent money could be made, more than a few took up the occupation full time. Some viewed it as a vocation; others only responded to requests for assistance after a cougar had killed livestock. Eventually, the role of a bounty hunter evolved into a combination of community service worker and paid assassin. Although such large-scale killing would not be sanctioned today, in their era, bounty hunters were highly respected and many became folk heroes and legends in their own time.

One of the most renowned was Ben Lilly, a mystical mountain man who believed he could communicate with animals and see inside their bodies to understand them on a physical and emotional level. Born in Mississippi in 1853, Lilly became obsessed with big game hunting after singlehandedly killing a bear with a knife. His chosen career took him from to Arizona to Idaho and down to Mexico. After a trip with Lilly as a hunting guide, Theodore Roosevelt noted that although Lilly was not a large man, his frame of steel and whipcord was capable of walking long distances without food, water or rain gear and never seemed to tire or mind rough terrain.

Frank Hibben took a three-day hike with Lilly in 1934. The eighty-year-old bounty hunter informed Hibben that bears and panthers were the Cains of the animal world and needed to be destroyed. Hibben had heard that Lilly was old and sick but what he found was a highly skilled woodsman who easily made his way across the landscape and who seemed to pick up panther sign by intuition and scenting the air like a dog. One evening Lilly led Hibben to a fresh panther kill and carved off a slab of venison for their dinner.

Lilly married twice and had several children who he supported but rarely saw. Preferring to be outside, the panther hunter disappeared for years at a time and pitied people who lived in towns and were forced to breathe rancid air. Lilly never indulged in alcohol, tobacco or coffee but regularly ate panther meat as he believed it increased his hunting abilities. Sundays were reserved for reading the Bibleif his dogs treed a panther on the Sabbath, he expected them to keep it there until Monday morning. Lilly shot most bears and panthers with a Winchester rifle but was also known to engage in paw-to-hand combat. His favourite weapon for this situation was a custom-made version of the bowie knife. He made his own knives out of scavenged steel, tempering them in panther oil.

As Lillys legendary status grew so did the number of animals he was said to have killed. Estimates put the figure for cougars at somewhere between six hundred and a thousand. He sent panther, bear, Mexican grey wolf and other specimens to the Smithsonian in Washington, DC , and in later years informed people he was writing a book. It had two chapters: What I Know About Bears and What I Know About Panthers. Lilly died in 193 6 n ear Silver City, New Mexico.

Next page