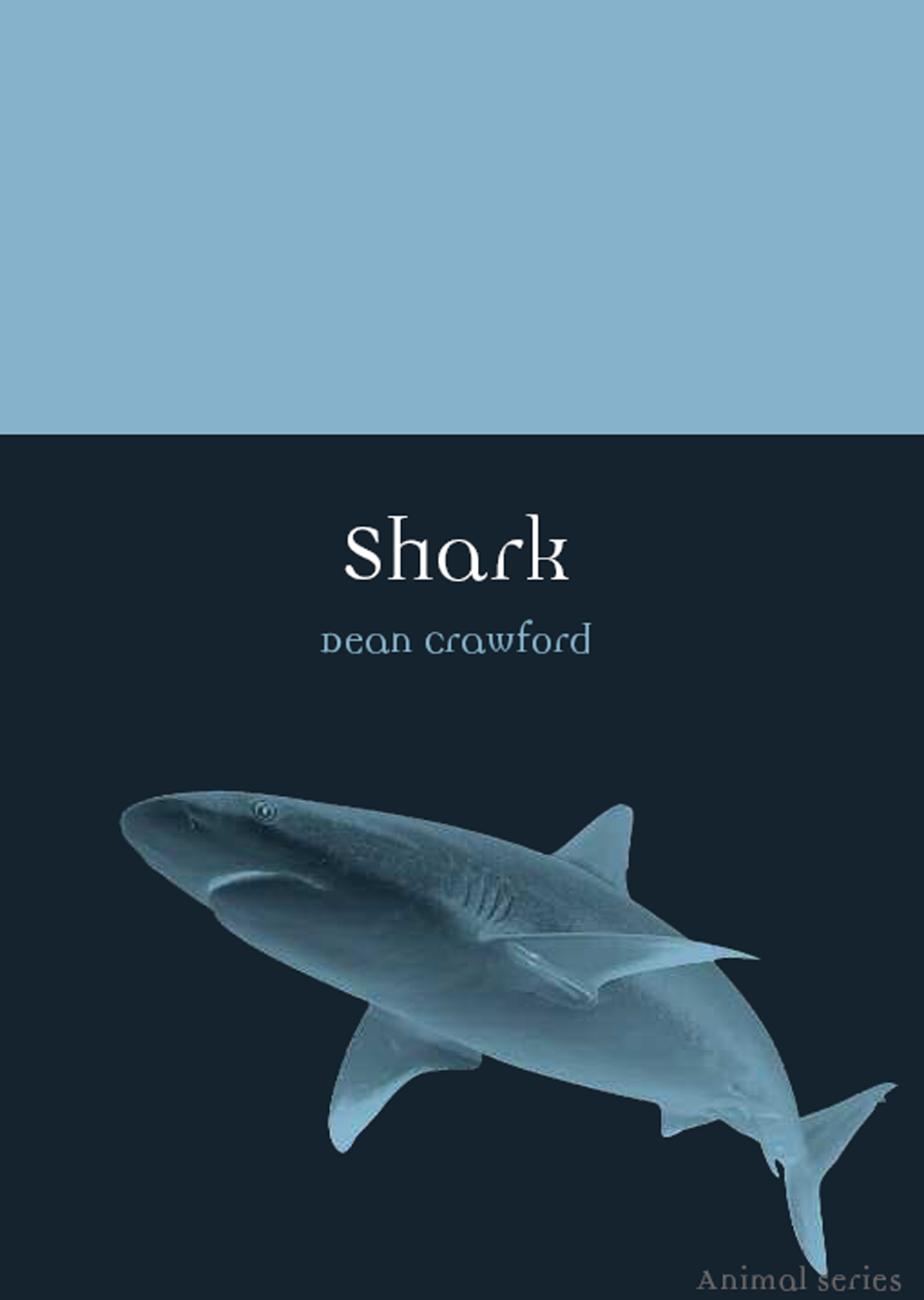

Shark

Dean Crawford

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2008

Copyright Dean Crawford 2008

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Crawford, Dean

Shark. (Animal)

1. Sharks 2. Animals and civilization

I. Title

597.3

eISBN: 9781861895004

Contents

Introduction

Sharks inspire terror out of all proportion to their actual threat. We may wonder what they did to earn such special attention. Did they chomp down on our prehistoric ancestors often enough to create an evolutionary memory, a kind of monster profile in the lower cortices of our brains? Or are we exercising that special combination of loathing and fascination that humans reserve for a predator at least as well designed and widely feared in its watery realm as we are on the land? Sharks are so other that they dont even have bones, but cartilage. Many shark species are ovophageous, meaning that they eat their siblings in the womb. When sharks feed, they shutter or roll back their eyes, giving them to our eyes an ecstatic expression. Their wriggling white bellies look obscene.

Whether from terror or excitement or some combination of the two, we all thrill to the sight of a dorsal fin cutting through the water. And yet, majestic as they may seem when glimpsed in the ocean, sharks are a challenge to love. Unlike wise old whales with their mournful tunes, or baby harp seals with their pleading eyes, some sharks are genuine monsters. Great white sharks weigh between one and two tonnes, more than an average car. Never mind that vehicles slaughter tens of thousands of us every year while sharks on average kill fewer than twenty worldwide. Sharks just look like thugs with those hunting-aroundeyes. Seen from the front, white sharks appear to be grinning. Then they turn to look at you with their flat, black, fathomless, alien eyes. Sharks behavioural habits are foreign to our tender mammalian sensibilities. All sharks are cannibals. Female sharks come equipped with a special mechanism to repress their hunger during and immediately after childbirth otherwise they would eat their own young. The white sharks favourite food is not family members, but the baby elephant seal, too small to defend itself with tusks or claws, too naive to know to avoid the sharks lurking along the bottom just off the beaches where elephant seals breed and give birth and the young must put to sea to survive.

What is it about sharks, especially the larger ones, that evokes the juvenile in some of us, the testosterone in others and awe in still others? Many people harbour a fear of sharks. Some of us have nightmares. Some of us are nervous even when swimming in a freshwater lake or pond. It is easy to see why normally courageous people might choose to sit on the beach rather than swim, why otherwise temperate people might take up arms against what they perceive to be a sea of troublemakers, or why awe might manifest itself as idolatry. We might say that these people go with their feelings, following their fears into avoidance, pugnaciousness or reverence. These categories of response are not mutually exclusive, however: many of us experience two out of three. We fear sharks, so we take to our boats to catch and kill them. Or we thrill to the power and beauty of sharks all the more because we fear them.

Peter Gimbel, the banker turned documentary filmmaker who organized the great shark expedition that became the film Blue Water White Death, admits to having a recurrent nightmare about sharks:

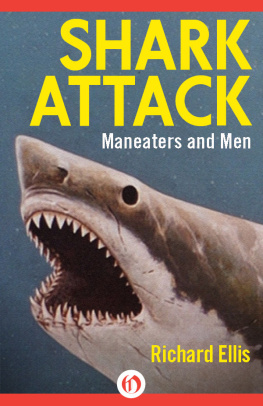

| The iconic Great White shark (Carcharodon carcharias), South Australia. |

Detailed as Gimbels nightmare may be, its one shared by many of us with a shark fascination: the aloneness in a vast ocean, theawareness of an approaching shark, the pressure wave, the overwhelming force, the consideration after waking in a cold sweat of whether it would be better to lose consciousness and drown or to expire more slowly while waiting for the shark to return for another bite.

Anyone who has seen Gimbels classic shark documentary (or read Peter Matthiessens narrative about the voyage, Blue Meridian: The Search for the Great White Shark) will remember the scenes of the oceanic whitetips feeding on the carcass of a whale. From the safety of the boat we see their dark shapes and wide pectorals beneath the surface, their distinctively rounded dorsal fins cleaving through the waves. These are the most feared open-ocean sharks, probably the greatest killers of all (many of their victims shipwrecked sailors and survivors of air disasters have gone unrecorded). Divers work from cages in the water filming the sharks dozens, maybe hundreds of them as they approach the whale, latch on, wriggle loose a huge bite and glide away, open-mawed, to swallow. In a kind of slow motion the sharks thrash and nip at each other. When the divers take a break to change tanks theyre grinning, aglow with excitement at what theyre catching on film. They complete each others sentences. Then Gimbel, a boyish gleam in his eye, proposes that he and the other divers leave the cages and swim freely among the feeding sharks. Ron Taylor, one of two Australians on the expedition, assents with a casual sure, mate; hes swum with huge sharks as recently as the night before. But Stan Waterman, an expert diver and adventurer, visibly stiffens at Gimbels suggestion. These sharks are 3.5 metres long; around the carcass the water is cloudy with whale blood and blubber. Yet Waterman goes along. Gimbels theory, which proves correct, is that sharks have no more than a passing interest in divers and can be easily fended off when one of theirfavourite foods, smelly dead whale, is nearby. However, in 1969, when Gimbels 1969 documentary was filmed, the feeding frenzy was still considered a scientific fact. Leaving their cages to mingle among the whitetips was a brilliant act of possible madness, inspired not only by a desire to get the best footage for the film but also by the divers willingness to risk their necks (literally), to take a swim on the wild side.