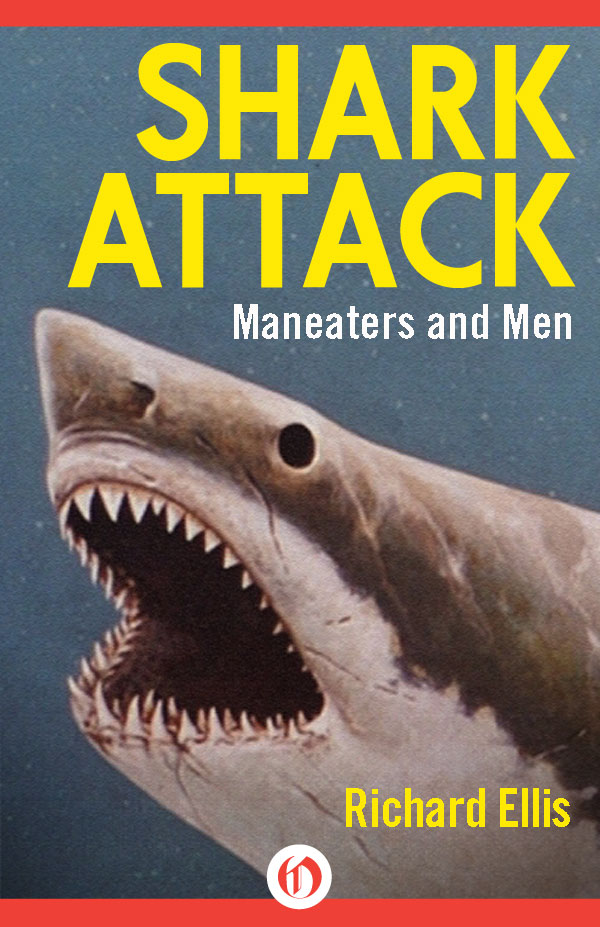

Shark Attack

Maneaters and Men

Richard Ellis

Part I

Shark Attack

Roger Kastels painting for the second paperback edition of Jaws.

Courtesy Roger Kastel

MORE THAN BEING BITTEN by a black mamba or a cobra; more than being mauled by a grizzly bear or chomped by a man-eating lion; more than being bitten by a black widow spider or a vampire batthe most terrifying moment in the ongoing conflict between man and beast is an attack by a shark.

We owe that state of fear to Peter Bradford Benchley.

The son of author Nathaniel Benchley and the grandson of American humorist and Algonquin Round Table founder Robert Benchley, Peter was an alumnus of Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard University. He worked for The Washington Post, as an editor at Newsweek, and as a speechwriter in the Lyndon Johnson White House. By the early 1970s, Benchley had gone shark fishing with Montauk monster fisherman Frank Mundus, was familiar with the worlds most famous shark attack off the New Jersey shore, and was generally well versed in the reputation of great white sharks. When the author pitched the idea of a novel about a great white shark terrorizing a beach community to Doubleday editor Tom Congdon, Congdon offered him an advance of a thousand dollars on submission of the first hundred pages. The newly minted author wrote the rest of the book during 1973 in a room above a furnace company in Pennington, New Jersey in the winter, and in the summer in a converted turkey coop in Stonington, Connecticut. Jaws became the publishing sensation of the winter of 1974. And in the novels opening paragraph, Benchley introduced the most infamous marine creature since Herman Melvilles Moby Dick, written 125 years earlier.

The great fish moved silently through the night water, propelled by short sweeps of its crescent tail. The mouth was open just enough to permit a rush of water over the gills. There was little other motion; an occasional correction of the apparently aimless course by the slight raising or lowering of the pectoral fins as a bird changes direction by dipping one wing and lifting the other. The eyes were sightless in the black, and the other senses transmitted nothing extraordinary to the small, primitive brain. The fish might have been asleep, save for the movement dictated by countless millions of years of instinctive continuity: lacking the flotation bladder common to other fish and the fluttering flaps to push oxygen-bearing water through its gills, it survived only by moving. Once stopped, it would sink to the bottom and die of anoxia.

In 1973, Universal Studios bought the rights to Benchleys novel. Filmed on Marthas Vineyard off the coast of Massachusetts, its star was a model of a great white shark the film crews nicknamed Bruce. According to Carl Gottlieb, a screenwriter who worked on Benchleys original script, the producers had innocently assumed that they could get a shark trainer somewhere, who, with enough money, could get a great white shark to perform a few simple stunts on cue in long shots with a dummy in the water, after which they would cut to miniatures or something for the close-up stuff. Unfortunately for the moviemakers, white sharks are notoriously uncatchable, not to mention untrainable, and the special effects department was set to work designing a shark that could pass the scrutiny of the most demanding viewer.

Australian shark expert Valirie Taylor says G-Day to one of the models of Bruce, the fake shark used in the making of Jaws.

Photo courtesy of Valirie Taylor

The film was released in the summer of 1975, and it was a huge success. In its June 23 issue, Time magazine declared it technically intricate and wonderfully crafted, a movie whose every shock is a devastating surprise. Its cover depicted an open-jawed shark with the caption Super Shark. Jaws was the biggest moneymaker in cinema history, and it spawned every conceivable spin-off, from plastic sharks teeth necklaces and T-shirts to lame imitations of Benchleys novel and lurid picture books about Jaws of Death! and Killer Sharks! There were now shark movies, shark novels, shark reports, and shark television specials.

How much of Jaws is true? Answer: Very, very little. Yes, there are great white sharks out there, and they occasionally bite people, but everything else about Jaws was wildly exaggerated fiction, from the size of the shark and its vindictivness to its hunger for human flesh. In a 1979 article in Skin Diver magazine, underwater cameraman Stan Waterman wrote, Something there is about the shark that continues to tickle the macabre fancy of man. And it is, of course, both simple and profitable to exploit.

Benchley may have read everything he could get his hands on about the 1916 attacks, yet most of what thought he knew was wrongattributed at the time to a single rogue shark that roamed the New Jersey beaches attacking swimmers, though it has now been shown to have been the work of several sharks, spread along ninety-five miles of coastline. To add insult to injury, the single rogue shark was most likely multiple bull sharks, not a great white. Truthfully, during a twelve-day period between in July 1 and July 12, no less than five men were attacked by sharks in New Jersey, four of them fatally. On July 1, twenty-three-year-old Charles Vansant, playing in the surf some fifteen yards from shore at Beach Haven, was bitten on the left thigh. Although companions dragged him ashore and quickly applied a tourniquet to his leg, he suffered a massive loss of blood, and he died less than two hours after the attack.

On July 6, at the beach resort of Spring Lake, some forty-five miles north of Beach Haven, Charles Bruder was attacked while swimming four hundred feet from shore, and both his feet were torn off. Although a lifeboat was launched immediately when he began to scream, and he was taken quickly to shore, he died within minutes.

Six days passed before another attack. Only July 12, at Matawan, thirty miles north of Spring Lake, eleven-year-old Lester Stillwell was swimming with friends when he was pulled under. Although a large dark-gray shark had been spotted in Matawan Creek earlier, nobody actually saw the shark that attacked Stillwell. Would-be rescuers dived into the creek to search for Stillwells body, and one of them, a twenty-four-year-old tailor named Stanley Fisher, was savagely bitten on the right thigh. A great chunk of his thigh was removed, and even though he was rushed to a hospital, there was no way to reverse the massive tissue and blood loss and he died on the operating table.

By this time, the news of the Matawan Creek attacks had spread, but not quickly or far enough to protect twelve-year-old Joseph Dunn, who was swimming a half mile away. Fortunately, although his lower left leg was bitten and severely lacerated, no bones were crushed and no arteries were severed, and Dunn made a full recovery.

Using dynamite, guns, harpoons, spears, and nets, the residents of Matawan assaulted the waterways, hoping to capture or kill all of the sharks in the vicinity. Although many sharks were thus dispatched, not one expert from any branch of law enforcement, ocean science, or marine biology was able to prove that a shark, or sharks, was responsible for the attacks in Matawan Creek. (Conceivably, the earlier attacks at Beach Haven and Spring Lake were the work of a single shark, but even that seems unlikely.) For two days, the newspapers were full of shark reports and stories of monsters caught in the region. Then, on July 14, a 7.5- to 8.5-foot white shark was trapped in a drift net in Raritan Bayjust four miles northeast of the mouth of Matawan Creekand bludgeoned to death by a man named Michael Schleisser. When this shark was cut open, it was found to contain fifteen pounds of flesh and assorted bone fragments, which may or may not have been human. One of those who positively identified the remains as human was Dr. Frederick A. Lucas, director of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, who, only a few days earlier, was quoted in the newspapers as saying that sharks could not possibly inflict the kind of damage that was done to Charles Bruder at Spring Lake.

Next page