Chapter 1

In the Beginning

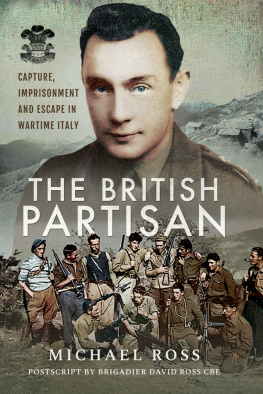

M y father survived the horrors of the First World War, where he served in the Royal Garrison Artillery, and returned home from France in 1919, which was very fortunate for me because I was born in 1920.

My early years were spent in a troubled world that was still reeling from the shock of the recent conflict. The people of Britain were desperate to forget the miseries of the war years whilst they struggled to cope with the problems of a changing way of life. These were the days of silly fashions and exaggerated gestures, when it was considered smart to dance the Charleston and for women to smoke cigarettes in long holders. Motor cars were now a common sight on the streets and almost every city had tramcars and motor buses, which made travel a great deal easier than it had ever been. Although people still worked long hours, holidays beside the sea were becoming popular during the summer months, but in spite of such changes there was still a great deal of poverty and unemployment as the country was going through a period of depression, and dole queues were a common sight. Some people were desperately poor and had to subsist with the aid of food tickets issued to the needy by the Board of Guardians.

The large majority of homes were without electricity and although many houses had gas lighting some still had to make do with paraffin lamps or candles as a means of illumination. Radio and television were things for the future and for me, as for many other children of my age, a visit to the cinema to watch a black and white silent film was a rare treat. I do not recall having many toys they were things to dream about but to compensate I did have the vital element of freedom, which enabled me to wander the countryside around our home without fear of molestation.

My formal education commenced when I was five years of age, but for me school was not a very happy place, largely because my temperament was not at all suited to the conditions imposed by mass education. It would be surprising if any of my teachers remembered me with any degree of warmth because I was far from the ideal pupil. It was not that I was cheeky or disobedient my upbringing made such behaviour unthinkable. At all times I was very polite and I really did try hard to please my teachers but, alas, with little success. They said that I had a good brain but was far too lazy to use it to any advantage. The teachers always complained I was too easily distracted and spent far too much time daydreaming. The latter was certainly true.

The truth of the matter was that I was bored to distraction for most of the time. There was too much chalk and talk and little opportunity to use ones own initiative, hardly any visual aids to the teaching and no individual attention whatsoever. Everything was served up in huge chunks of knowledge, delivered in long, tedious oral lessons which droned on and on and on, and I would quietly slip away from it all, becoming lost in my own thoughts. Often, at the end of a lesson, a furious and frustrated teacher would discover that I hadnt heard a word that had been said. I must have been a very trying pupil!

In spite of my unco-operative attitude and lack of industry, I quickly learned to read. This was one of the greatest blessings of my life and my everlasting thanks go out to those underpaid spinsters who gave me this skill. (There were no married women teachers in those days.) Reading opened the door to a whole new world and I took full advantage of this wonderful gift, reading almost everything that came to hand. I loved reading and consumed books with an insatiable appetite.

In many ways I had a good home, and compared with many of my schoolfellows I was showered with the good things of life. There was always an abundance of wholesome food, all my physical needs were well catered for and there were books that fed my imagination with a host of fascinating ideas that found an outlet in my play. Tales of Robin Hood, Coral Island, Treasure Island, stories from the Great War and history, sea yarns, tales of the outback or the prairies, cowboys and Indians: these were the stuff of which dreams were made. The heroes were always men of courage and integrity, there was no dallying with half-measures, no making of excuses for those of evil intent, and cowards were not to be tolerated under any circumstances. Things were black or they were white; men were either goodies or they were baddies and the goodies always won, or they died with their faces towards the enemy, steadfast to the end.

I often feel sorry for the children of today, surrounded as they are by expensive toys, radios, televisions, computers, electrical robots of various kinds and numerous plastic articles that carry the name toys but are really just useless lumps of synthetic material. It is sad to see healthy children, bursting with energy, trapped in stuffy, overheated rooms. They have their eyes glued to television screens, while outside the sun shines on empty woods and fields and birds fly unheard and unseen by a generation of children who have lost the freedom that we enjoyed so much when I was young.

During those early years I spent some of my happiest hours with my two older brothers in a hut which father had built for us in the garden. It was constructed from sheets of corrugated iron, nailed to a framework of timbers. In the hut was a slow combustion stove that stood on a stone slab, and there was a long stovepipe chimney that went up through the roof. This hut was the focal point of all our games. Sometimes it was a dugout on the Western Front, from which we would sally forth with bayonets fixed to charge the German enemy across the mud of Flanders. On other days, with smoke pouring from the chimney, it became the engine room, or the bridge, or both, of a destroyer battling against the stormy winds of the North Atlantic. On cold, winter days it was often a trappers hut or an outpost of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in the frozen Yukon. In summer it could easily become a covered wagon from which we fought off hordes of savage, painted, screaming Red Indians.

It was in this way that I played my way through my boyhood days. I was brought up to know where my duties lay. First to serve God by trying to be good. Then to be fiercely patriotic and to serve the King by being brave. I was to emulate the spotless knight, the unsullied hero, the faithful comrade and the soldier who went unfalteringly into battle. All this was rather a tall order for a thin and rather timid little boy who was afraid of the dark and who wouldnt have dared say Boo to a goose.

Most of our games revolved around fighting and killing. The influence of the Great War was still very strong, and death in battle was an accepted part of our play. We would throw up our arms and crash to the ground feigning death from machine-gun bullets, shrapnel or shell splinters. When I became a soldier many years later, no one had to teach me rifle drill: I had become familiar with that long before I was ten years old. I shall never know how many years of my childhood I spent marching up and down our garden path with an air rifle on my shoulder. Being the youngest brother meant that I was always the most junior rank in whatever game we were playing. George and Rupert, my two brothers, could be captains or colonels, even generals if they so wished, but I was always the poor old private soldier flogging up and down the garden path on sentry go. A fitting augury for what was to follow!

During my teenage years my brother Rupert was transferred to another branch of the company which employed him and this meant that he had to leave home and go to live in Northampton. I well recall the great sense of loss I felt when he went away and the eagerness with which I greeted his return each weekend. Almost every weekend for three or four years he came home on Saturday evening in order to spend Sunday with us and in all that time I dont think I ever missed being at the Midland station in Nottingham to meet his train which arrived at eleven oclock.