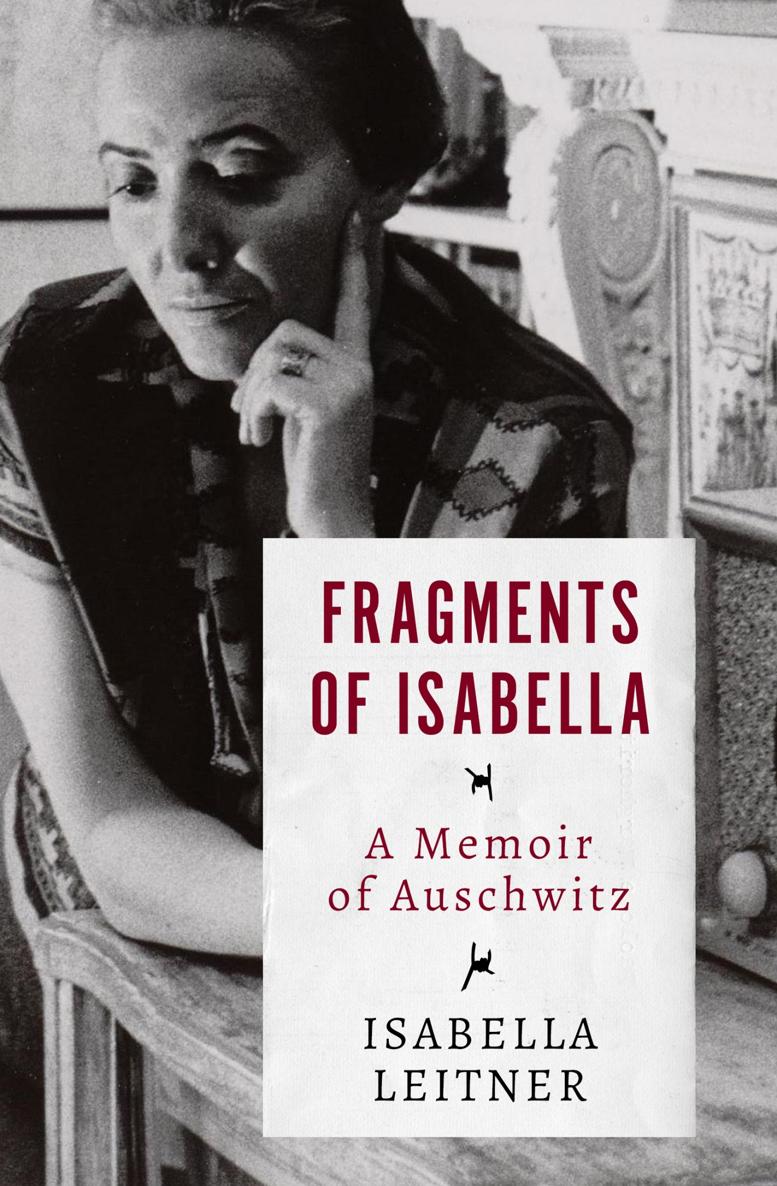

Praise for Fragments of Isabella

This is one of the ever-glowing gems of the Holocaust experience. Meyer Levin, author of Compulsion

Profoundly moving Leitner writes with a searing sensitivity that can move one to tears. Her slim volume is a celebration of the strength of the human spirit as it passes through fire. Publishers Weekly

A luminous and moving work, and an invaluable addition to the literature of historys most terrible tragedy A voice not of defeat, but of affirmation. Gerald Green, author of Holocaust

Commands immediate nonstop reading. [Leitner] writes sparely, hauntingly, about very specific detailsfaces, voices, in a way that renders the unbearable real. She breaks my heart open. Phyllis Chesler, author of Women and Madness

Isabella Leitner has helped to teach a new generation that we must not forget the past. She has done this in a moving and truthful way. Elizabeth Swados

Fragments of Isabella

A Memoir of Auschwitz

Isabella Leitner

The recall was painful.

My husband tiptoed around

me with deep, delicate concern.

This book belongs to him.

Isabella

You dont die of anything

except death.

Suffering doesnt kill you.

Only death.

NEW YORK, MAY 1945

Yesterday, what happened yesterday? Did you go to the movies? Did you have a date? What did he say? That he loves you? Did you see the new Garbo film? She was wearing a stunning cape. Her hair, I thought, was completely different and very becoming. Have you seen it? No? I havent. Yesterday yesterday, May 29, 1944, we were deported.

Are the American girls really going to the movies? Do they have dates? Men tell them they love them, true or not. Their hair is long and blonde, high in the front and low in the back, like this and like that, and they are beautiful and ugly. Their clothes are light in the summer and they wear fur in the winterthey mustnt catch cold. They wear stockings, ride in automobiles, wear wristwatches and necklaces, and they are colorful and perfumed. They are healthy. They are living. Incredible!

Was it only a year ago? Or a century? Our heads are shaved. We look like neither boys nor girls. We havent menstruated for a long time. We have diarrhea. No, not diarrheatyphus. Summer and winter we have but one type of clothing. Its name is rag. Not an inch of it without a hole. Our shoulders are exposed. The rain is pouring on our skeletal bodies. The lice are having an orgy in our armpits, their favorite spots. Their bloodsucking, the irritation, their busy scurrying, give the illusion of warmth. Were hot at least under our armpits, while our bodies are shivering.

MAY 28, 1944MORNING

It is Sunday, May 28th, my birthday, and I am celebrating, packing for the big journey, mumbling to myself with bitter laughtertomorrow is deportation. The laughter is too bitter, the body too tired, the soul trying to still the infinite rage. My skull seems to be ripping apart, trying to organize, to comprehend what cannot be comprehended. Deportation? What is it like?

A youthful SS man, with the authority, might, and terror of the whole German army in his voice, has just informed us that we are to rise at 4 A.M. sharp for the journey. Anyone not up at 4 A.M. will get a Kugel (bullet).

A bullet simply for not getting up? What is happening here? The ghetto suddenly seems beautiful. I want to celebrate my birthday for all the days to come in this heaven. God, please let us stay here. Show us you are merciful. If my senses are accurate, this is the last paradise we will ever know. Please let us stay in this heavenly hell forever. Amen. We want nothingnothing, just to stay in the ghetto. We are not crowded, we are not hungry, we are not miserable, we are happy. Dear ghetto, we love you; dont let us leave. We were wrong to complain, we never meant it.

Were tightly packed in the ghetto, but that must be a fine way to live in comparison to deportation. Did God take leave of his senses? Something terrible is coming. Or is it only me? Am I mad? There are seven of us in nine feet of space. Let them put fourteen together, twenty-eight. We will sleep on top of each other. We will get up at 3 A.M. not 4stand in line for ten hours. Anything. Anything. Just let our family stay together. Together we will endure death. Even life.

MAY 28, 1944AFTERNOON

We are no longer being guarded only by the Hungarian gendarmes. That duty has been taken over by the SS, for tomorrow we are to be transported. From now on, the SS are to be the visible bosses.

Before this day, Admiral Horthys gendarmes were the front men. Now they are what they always had beenthe lackeys. Ever since childhood, I remembered them with terror in my heart. They were brutal, viciousand anti-Semitic. Ordinary policemen, by comparison, are gentle and kind. But now, for the first time, the SS are to take charge.

My mother looks at me, her birthday baby. My mothers face, her eyes, cannot be described. From here on she keeps smiling. Her smile is full of pain. She knows that for her there is nothing beyond this. And she keeps smiling at me, and I cant stand it. I am silently pleading with her: Stop smiling. I gaze at her tenderly and smile back.

I would love to tell her that she should trust me, that I will live, endure. And she trusts me, but she doesnt trust the Germans. She keeps smiling, and it is driving me mad, because deep inside I know she knows. I keep hearing her oft-made comment: Hitler will lose the war, but hell win against the Jews.

And now an SS man is here, spick-and-span, with a dog, a silver pistol, and a whip. And he is all of sixteen years old. On his list appears the name of every Jew in the ghetto. The streets are bulging with Jews, because Kisvrda, a little town, has to accommodate all the Jews of the neighboring villages. The SS do not have to pluck out every Jew from every hamlet. That work has already been done by the gendarmes. The Jews are now here. All the SS have to do is to send them on their way to the ovens.

The Jews are lined up in the streets. And now the sixteen-year-old SS begins to read the names. Those called form a group opposite us. Teresa Katz, he callsmy mother. She steps forward. My brother, my sisters, and I watch her closely. (My father is in America trying to obtain immigration papers for his wife and children, trying to save them before Hitler devours them.) My mother heads toward the group.

Now the SS man moves toward my mother. He raises his whip and, for no reason at all, lashes out at her.

Philip, my eighteen-year-old brother, the only man left in the family, starts to leap forward to tear the sixteen-year-old SS apart. And we, the sistersdont we want to do the same?

But suddenly reality stares at us with all its madness. My mothers blood will flow right here in front of our eyes. Philip will be butchered. We are unarmed, untrained. We are children. Our weapon might be a shoelace or a belt. Besides, we dont know how to kill. The SS whistle will bring forth all the other SS and gendarmes, and they will not be merciful enough to kill the entire ghettoonly enough to create a pool of blood. All of this flashes before us with crystal clarity. Our mothers blood must not be shed right here, right now, in front of our very eyes. Our brother must not be butchered.