Yet, my little Diary, I dont want to die, I still want to live

va Heyman, a thirteen-year-old Jewish girl, wrote these words in her last diary entry in the spring of 1944. Soon after, she was deported and murdered at Auschwitz. During the Holocaust, the Nazis killed more than one million people at Auschwitz. The largest of all the Nazi camps, Auschwitz was both a death camp and a forced labor camp. Author James M. Deem examines this place of unspeakable horror from the perspective of those who experienced it.

James M. Deem presents an overview of the greatest killing center ever created and the people, perpetrators, inmates and escapees, Jews and Gypsies, those who worked in the gas chambers and crematoria and those who created the institution known as Auschwitz. Important reading about an essential place. Highly recommended.

Dr. Michael Berenbaum, Executive Director of the Encyclopedia Judaica and Former Project Director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

About the Author

James M. Deem is a retired college professor and the author of many books for young people, including Primary Source Accounts of the Revolutionary War for Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Contents

In May 1944, Olga Lengyel went to the Cluj, Hungary, train station with her husband, Miklos, and their family. A prominent Jewish doctor, Miklos had been accused by German authorities, who now controlled Hungary, of refusing to use German-produced drugs in his medical practice; he was told that, as punishment, he was to be deported to Germany. Olga and her parents decided to join Miklos on the deportation train; the couples young sons would come, too.

But when the family arrived at the station, Olga found a train of cattle cars, many already crammed with Jews from Cluj and other Hungarian towns. Olga and her family were shoved into a car with ninety others, confined to a space that would have held only eight horses. The Germans had lied to them.

During the seven-day journey that followed, the passengers were given no food and almost no water. Half of the people in Olgas car had no room to sit. A few families had brought chamber pots, and these became makeshift toilets in one corner of the car. When they were full, the pots were emptied out of a small windowthe only window in the car.

On the second day, a man died of a heart attack; when the train stopped at the next station, the guards told the dead mans son to Keep your corpse. You will have many more of them soon!

On the third day, a guard shouted through the window at one station, Thirty wristwatches, right away. If not, you may all consider yourselves dead! Olgas son, Thomas, gave up the wristwatch he had been given in third grade.

The guard returned, demanding fountain pens and briefcases. The third time, he promised that, if the passengers gave him their jewelry, he would bring them some water, the first they had been offered on the trip. When the jewelry had been collected, a bucket of water was lowered into the car. But many of the passengers did not get a drop.

During the next four days, more people died from disease, from heat, from thirst, from hunger. On the seventh day, the train reached its final destination. When the train door was finally opened, the trainload of Jews had no idea where they were. Confused and frightened, they were ordered out of the cattle cars by German soldiers. Men were told to stand in one line; women and children in another. Olga saw thousands of Jewish passengers standing on the platform. Nearby, emaciated men in striped prison uniforms took their belongings from the train. Next, the men removed the corpses from each car.

A group of German officers began to separate the passengers further. Somethe children, the elderly, the sick, the disabledwere sent to the left. Everyone else was waved to the right. Anyone who complained was beaten immediately until he or she complied.

When it was Olgas turn, she was motioned to the right with her mother. Thomas was sent to the left. But the German officer hesitated when he saw Olgas other son, Arvad.

Image Credit: USHMM, courtesy of Yad Vashem

Jewish women and children deported from Hungary wait in line at Auschwitz after being separated from the men in May 1944. Olga Lengyel went through this process when she arrived at Auschwitz with her family.

This boy must be more than twelve, the officer told Olga.

Thinking that the childrens line might receive special care, she told the officer that Arvad was not yet that old. The officer sent Arvad to the left. Now that her sons seemed to be safe in the group on the left, Olga asked if her mother could change lines to help care for her sons. The officer agreed.

Then the line on the left was marched away, unaware of what would happen next. It was only laterafter she was shorn of her hair, searched, disinfected, and dressed in old clothesthat Olga learned where she was. She and her family had been taken to Auschwitz, a concentration camp in German-occupied Poland that had become a death camp for Jews and others that the Nazis considered undesirable. After they left the train platform, Olgas sons and parents had been taken to a gas chamber and killed with everyone else in the left-hand line.

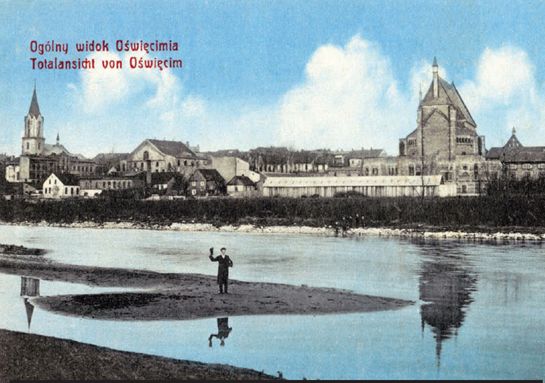

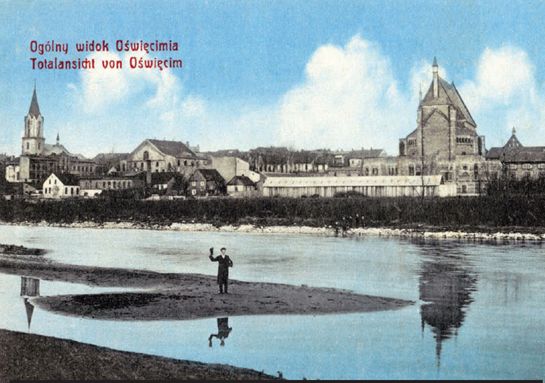

Auschwitz, as it was known in Germany (or Oswiecim in Poland), was selected to be a concentration camp in February 1940, some five months after Germany invaded Poland to begin World War II. Nazi officials thought an old Polish military camp on the outskirts of town would provide a good foundation for konzentrationslager (or KL) Auschwitz.

On April 30, 1940, Rudolf Hss, the first commandant of KL-Auschwitz, arrived to remodel the run-down barracks. At first, KL-Auschwitz was intended to be a short-term holding camp for Polish political prisoners before they were shipped off to other camps.

Image Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / The Image Works

This is a postcard with a view of the old town in Oswiecim, or Auschwitz, at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Auschwitz I was the original camp and administrative center. Prisoners entered this camp under a large iron gateway that said: Arbeit Macht Frei (Work will set you free). At first, Polish prisoners were housed there in barracks (called blocks). They added second stories to the one-story barracks and built additional blocks to house an increasing number of prisoners. But there were no rewards for the labor, which was required in all types of weather. Although the death of a prisoner was not the intended result at first, some prisoners did die from natural causes, from brutal punishment, or from the harsh conditions in which they were forced to live. Their bodies were incinerated in a small crematorium within the camp proper.

The most-feared barrack was Block 11, the jail. There, prisoners receiving punishment were often placed in cramped basement cells and deprived of food. Prisoners sentenced to death were executed by gun in the courtyard between Block 10 and Block 11, usually against the so-called Black Wall.

In September 1941, camp officials decided to experiment with a new method of execution, a poison gas called Zyklon B; they gassed a group of Soviet POWs in the basement of Block 11 with the new poison. When that proved successful, a larger group of some nine hundred Soviet POWs were gassed in the crematorium (now called Crematorium I) and their bodies were burned in the adjacent ovens.