Copyright 2017 by Purdue University Press. First printing in hardback, 2018.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-55753-824-6

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier paperback edition as follows:

Names: Bacon, Ewa K., author.

Title: Saving Lives in Auschwitz: The Prisoners Hospital in Buna-Monowitz / Ewa K. Bacon.

Description: West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, [2017] | Series: Shofar Supplements in Jewish Studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers:

LCCN 2017012197

ISBN 9781557537799 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781612494920 (epdf)

ISBN 9781612494937 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Budziaszek, Stefan. | Auschwitz (Concentration camp) | Jewish physiciansMedical care. | Concentration camp inmatesMedical care. | World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, Polish. | Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)

Classification: LCC D806 .B33 2017 | DDC 940.53/18092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017012197

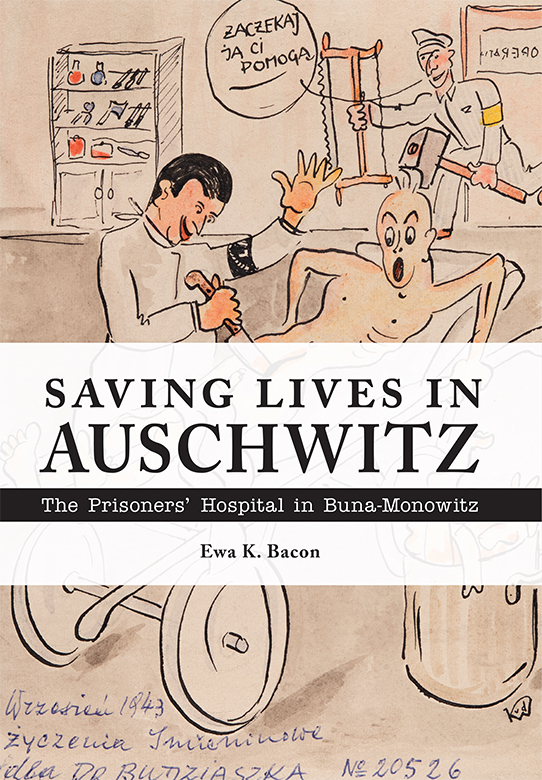

Cover: The image used on the cover is a never-before-published artifact from within the prison, taken from a hand-drawn gift card, a name-day card, given to Stefan by a fellow prisoner. As only art can and with the candor of dark prison humor, it speaks to the complex double-bind of doing no harm, while assisting the SS and saving lives in Auschwitz. The full image appears and is discussed here publicly for the first time.

My father had a tattoo. It was a faint blue line on his left forearm, 20526. Growing up in Germany, I saw that many adults around me also had a tattoo. My parents and I were displaced persons stranded outside of Poland in the British occupation zone of Germany. I spoke Polish at home and German in school. I knew the term DP (Displaced Persons) and I knew that we werent really home, that we lived, as the Poles would say, outside the border. Many DPs were scattering, moving away from Germany. I was not at all aware of the difference between those DPs with tattoos who were Roman Catholic and those with tattoos who were Jewish.

My father, Stefan Budziaszek, was a doctor and my mother, Ewa Irena, was a nurse. They met and married in the chaos of postwar Germany in 1945 and their marriage had disintegrated by 1954. It was perhaps not an uncommon event, but it represented an enormous break in my life. Both parents immediately remarried and my mother and I and my step-father, Jerzy Kujawski, left Germany for Sweden and three years later, in 1957, for the United States. My father married a German Jewish woman, had a son, Stevie, and stayed in Germany. I didnt see him again or meet his new family until I was 19, a student at Stanford University, and traveling back to Germany for the first time.

He still had the tattoo and I now knew that meant he had been a prisoner in a concentration camp. It was accepted and not a matter for discussion, even in the family. Neither he nor his friends talked about those years. It was much like other veterans of other wars: it was better not to bring it up. It was not until 2002, some eight years after my fathers death in 1994, when I received a large carton of documents from Germany, that I had access to any information about those war years. By now I was a historian. Since I am a native speaker of both Polish and German, I specialized in Central European history. But I had no research agenda that dwelled on Auschwitz. In the United States, when I mentioned the tattoo and Auschwitz, I had to repeatedly explain that yes, my father had been in Auschwitz, and, no, he didnt die there. No, we were not Jews, and yes, many other non-Jews were also in the concentration camps.

The terms Holocaust and genocide were now in wide currency. The enormity of the Jewish Shoah became the subject of intense study. Scholars listened to Holocaust survivors and documented their stories. There was not, however, a collective noun for non-Jewish survivors or victims. There still is not. Those Holocaust survivors who formed families raised children who were identified as second generation victims, as in Art Spiegelmans graphic novel, Maus. I also belong to a second generation, but I do not share in the level of trauma of the Jewish cohort. Non-Jewish victims of Nazi atrocities are only labeled by their nation: Poles, Dutch, French, and so on, and thus were subsumed by a political identity.

I found a deeply fascinating document among my fathers papers: a transcript of his oral testimony to the museum and research center established in Auschwitz after the war. This was the first time that I had access to a coherent narrative of his war experiences, and I found it startling and exciting on many levels. First, it was part of my family history and formed the subtext to my upbringing. Second, it was a primary historical document, a rare and valuable source to a working historian. Third, it was like nothing that I could have imagined. Here was the full story of political intrigue, of arrests and beatings, of transfer to the notorious death site, Auschwitz, of some place called Buna, of improbable achievements, and finally of rescue and survival. I was determined to translate this Polish document into English, a language that my children could read, so they could share this story.

I am thus writing for the third generation of survivors. As a historian I am familiar with the context of the war and its perpetrators and understand the rise of Nazis in Germany and the vast cast of characters involved. But I quickly realized that my third generation children and their compatriots do not have any great familiarity with this information. The names and places and details of my father Stefans story needed a context.

Who were these Nazis and why did they attack Poland? What was their attitude toward Slavs? Why did they arrest educated people? Why would a world-famous German company decide to build a factory near Auschwitz? Who were the Auschwitz inmates? Who were the jailors? Who were the prisoners? How was Auschwitz managed? Why did conditions in Auschwitz change? What is the difference between a labor camp and an extermination camp? How was Auschwitz different for Jewish inmates? How was it possible to survive what more than one survivor called the anus mundi? Fundamentally, was Stefans story verifiable? Who could substantiate his narrative?

Many of my stereotypical assumptions about Auschwitz were shattered as I assimilated Stefans story. Fundamentally, Auschwitz was a political prison and a labor camp. It was not planned with gas chambers and crematoria; those instruments of genocide developed over time. Stefan and his fellow long-term prisoners were distinct from the vast multitude of Jewish families swept up across Europe and shipped to Auschwitz to be exterminated. Prison laborers, both gentile and Jewish, had to deal with quotidian details: food, shelter, clothing, health, fellow prisoners, and jobs. Skills mattered, giving working prisoners a level of agency in a brutal system. Nazis used prisoners who were carpenters or electricians to build the camps. They also used prisoners who were doctors to deal with injuries and diseases.