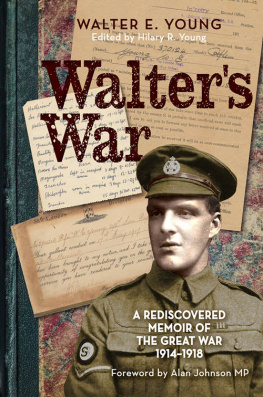

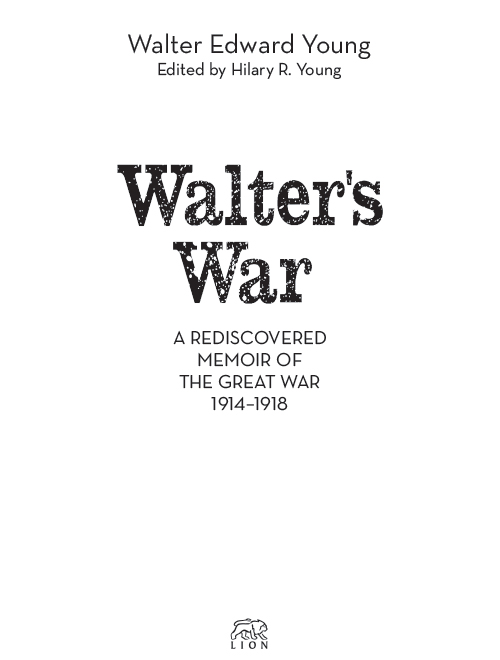

Introduction and additional text copyright 2015 Hilary R. Young

Original diaries and letters copyright Hilary R. Young

This edition copyright 2015 Lion Hudson

The right of Hilary R. Young to be identified as the author of the introduction and additional text is asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Lion Books

an imprint of

Lion Hudson plc

Wilkinson House, Jordan Hill Road,

Oxford OX2 8DR, England

www.lionhudson.com/lion

ISBN 978 0 7459 7030 1

e-ISBN 978 0 7459 7031 8

First edition 2015

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover images courtesy of Hilary R. Young

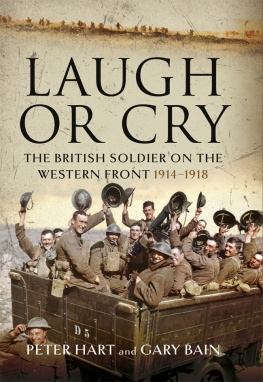

A gripping, compelling memoir of a good man in extraordinary times.

DUNCAN BARRETT, author of Men of Letters

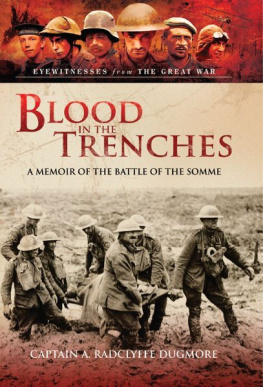

Factual books providing this excellent basement level view of World War I are rare. Young... provides a meticulous, almost dispassionate record of day-to-day life and death during those terrible years. He leaves it to the reader to imagine the destructive impact such hardship and grief has upon the human soul, both at the time it is happening and in the years after the conflict has ended.

DALE LE VACK, co-author of Stretcher Bearer!

A Post Office sorter, a quiet, careful man, finds himself fighting for his country in France. He records his war story step-by-step in the penetratingly clear language of an able man.

PROFESSOR G. R. EVANS, author of Edward Hicks:

Pacifist Bishop at War

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

When I became a postman in 1968 nothing much had changed in the 128 years since the modern Post Office emerged through Roland Hills reforms. We postmen were uniformed civil servants working for the General Post Office (GPO), proud to bear a crown on our cap badge and to be entrusted with the Royal Mail.

A mainly male occupation, almost all my fellow postmen at Barnes (London SW13) were ex-servicemen. It was a natural environment for their return to Civvy Street; a uniformed occupation with a military hierarchy. We didnt come to work we came on duty; we didnt take holidays we took annual leave. There was little new technology (or mechanisation as we called it at the time). Mail was collected, faced, sorted, despatched, received, sorted again, and delivered entirely by hand.

This process would have been entirely familiar to Walter Young, whod retired as a central London postman long before I joined the service. But his generation of postmen werent the soldiers whod become the postmen that I worked beside at Barnes; they were in the main postmen whod become soldiers in a war they were told would be over by Christmas, whod joined up in a patriotic fervour that sent so many men to their deaths.

Walter was already partially conscripted, having joined the Post Office Rifles a while before the First World War broke out. Duncan Barretts splendid book Men of Letters told the story of this territorial unit of postal workers which distinguished itself on the battlefield, while their more fortunate colleagues were drafted into the slightly less dangerous task of ensuring that a swift and efficient mail service operated between the men in the trenches and their families back home.

In this amazing memoir we get a first hand account of what it was actually like for a quiet, modest, God-fearing postman to be plunged into the blood and carnage of trench warfare.

The reality becomes apparent early on for Walter. He and his unit hadnt reached the front line when they see the 4th Cameronians and a battalion of the East Yorks going up to make an attack in perfect formation, the officers immaculate, the men full of patriotic bravado. The next morning they witnessed their return journey in ones and twos they came, wild eyed and without a rifle or equipment in many cases; clothing torn and muddy each one seemed to think he was the only survivor.

These men had been detailed to advance the front line by 1,000 yards in the dark. Nobody informed them that there was a broad ditch and stream in front of the enemy trenches. They had floundered helplessly while being picked off by the German troops above them.

Walters description captures in a couple of paragraphs all the vain, glorious stupidity of those controlling the infantry, and the stark reality of the war he was being sent to wage.

He was soon to experience these horrors for himself. The wonder is how staunchly he maintained his civility and his quiet, unassuming Christianity, amidst the barbarity.

Even his teetotalism survives. Hes the only one in his Company to refuse the rum ration, and when offered a glass of wine by two grateful French women whose drain hes unblocked, he waves it away trying to explain that he required no reward. Avec plaisir, he repeats over and over using the Army phrase book that he had studied meticulously.

This contrast between the horrors of the front line and the domestic peace of French villages a mile or so away never occurred to me until I read Walters incredible account. He visits the town of Bthune in one break from warfare with its lights and shops and men and women going about their business. Billeted to another pretty village, his hosts laid a tablecloth for dinner, with one or two vases of tastefully arranged flowers.

This contrast between spells of fighting and breaks in the French countryside must have seemed like travelling between heaven and hell for riflemen such as Walter.

And what hell he was forced to endure; at Festubert, Vimy Ridge, Ypres, Crozat Canal. On and on he went watching good friends blown to pieces before his eyes; crawling over rotting bodies; living in damp, rat infested conditions; engaged in endless battles.

The reader is overjoyed for Walter when his five year stint in the territorial unit finishes in April 1916. He was marked to go and expected to resume his shifts as a sorter at the King Edward Building in Holborn forthwith. But he decides to go back to the trenches, accepting fifteen pounds and a months leave to be re-united with his regiment in France.

By this time Walter detested militarism wholeheartedly and longed to be one of the lucky beggars inflicted with a Blighty wound (a minor battle injury that was nevertheless serious enough to require hospital treatment back in Britain). However, he reasons that if conscription was introduced hed have to go back anyway without the fifteen pounds and could be sent to any regiment. By accepting the offer he at least returned to the Post Office Rifles where his friends were (those who were left alive).

That thought process is so typically Walter that, whilst the reader fears for the consequences, we can only admire the logic that takes our hero back to the inferno of the Western Front.

There is much more in store for Walter Young. He wins the Military Medal for bravery, becomes a stretcher bearer, and ends up as a prisoner of war in a German prison camp.

After the war Walter returns home, dons his blue Post Office uniform, and sorts letters for the rest of his working life. He marries Elsie from the Isle of Wight, raises a family, cultivates an allotment, and enjoys playing cricket and going for long walks. In the Second World War he volunteers to be a fire fighter.

Although he emerged from the trenches virtually unscathed physically, Walter has mental scars that are deep and profound. He suffered terrible headaches and bouts of depression relating to his wartime experiences. Like most soldiers he could never talk about the terrible things hed seen.