THE LAST BATTLE

Peter Hart is the oral historian at the Imperial War Museum and has written several titles on the First World War. His latest books for Profile are Gallipoli, The Great War and Voices from the Front.

PETER HART

THE LAST BATTLE

ENDGAME ON THE WESTERN FRONT, 1918

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Peter Hart, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 176 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I remember someone saying before the war that he imagined that when troops were in action under fire, each man thought to himself that whoever else might be hit, he himself would be alright. Well I dont think this is correct at any rate not in this war. I think men fully expect to be hit or killed, but carry on just the same. Personally, I was always thinking I was going to get hit or killed and was often surprised when I found I wasnt.

Captain Henry Owens, 57th Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps, 57th Brigade, 19th Division

IMAGINE IT IF YOU CAN. You have been fighting for four long years. Somehow you have survived, although many of your friends are dead. Now, just when your ordeal seems to be coming to an end, you are required to make one last effort, risking life and limb in the closing battles to hammer home the defeat of the German Army. Not everyone can take it easy on the final straight; not every soldier can shell hole drop, falling back during attacks and leaving others to lead the way. The temptation to shirk must have been enormous. Yet, for the most part, men dug deep within themselves to summon up the resolve to fight on and finish the job. For many it would prove the greatest sacrifice. They were fatally struck down just when a resumption of their civilian life was almost within touching distance. The Allies may have been winning, but the casualty rates in the closing six weeks of the war were excruciating. Open warfare may have freed them from the grim tyranny of the trenches, but it left them exposed to even greater perils. The beckoning necessity of finishing the war, to avoid the spectre of a new harvest of death in 1919, meant that corners had to be cut, risks taken and lives lost. It may have been logical, but it was no less painful to the individuals caught up in their own personal Armageddon.

A great deal of attention is paid to the opening moves made in wars. This is particularly evident with the Great War. Much of the media interest during the recent centenary celebrations was taken up with an exhaustive coverage of the 1914 campaigns, with British attention focused almost entirely on the Battle of Mons. The treatment of the rest of the war has concentrated on the Allied defeat at Gallipoli, or the long drawn out tragedies of the Somme, Verdun and Passchendaele battles. There is also an obsession with the brilliance displayed by Germans in their tactical conduct of the Spring 1918 offensives. The result of such fixations is that the ultimate Allied victory a few months later must come as a real surprise as suddenly the war is all over in November 1918. We need to explain what happened in the last few months of the war. From where exactly did the Allied victory emerge? Was the German Army really beaten? What havent we been told in many of the conventional accounts of the war?

Certainly, one underlying truth of the Great War must be driven home: the war finished with the collective armies of France, Britain, America and Belgium achieving total domination over the German Army on the Western Front. It was in fact a rejection of this that formed the basis of the puerile Nazi voices of the inter-war years that told the Germans that they had been stabbed in the back; that their army had never been defeated, that it had stood tall and strong, only to be overwhelmed by a combination of enemies within the state, in particular Communist agitators, their fellow travellers in the Labour movement and from their crazed perspective the Jews.

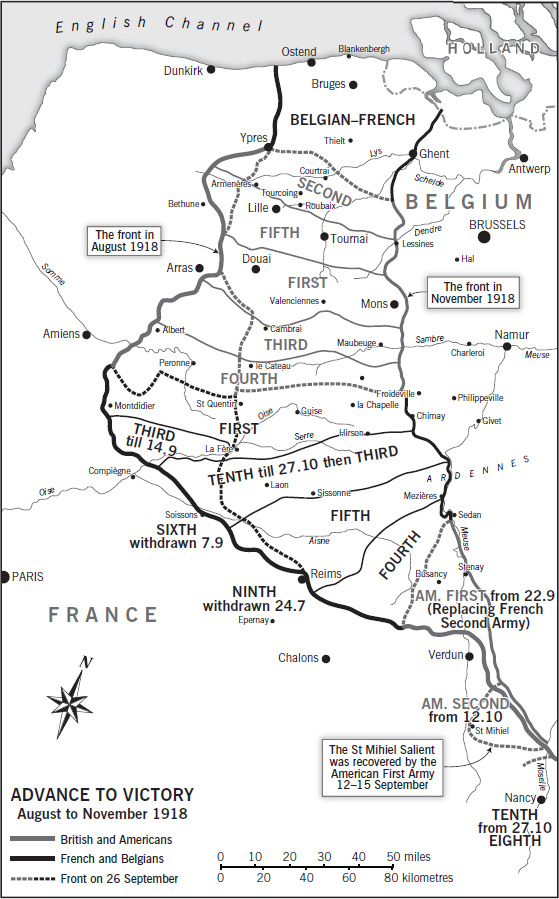

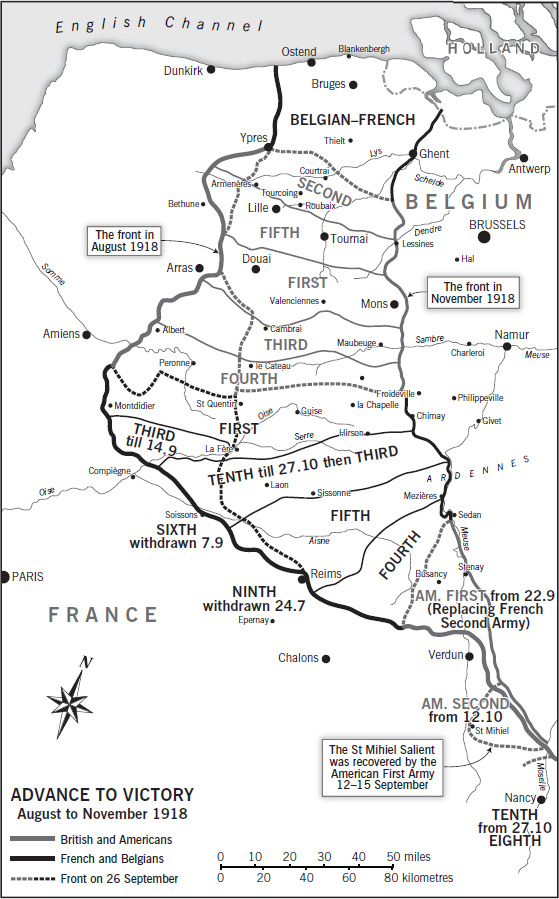

In reality, the Allied victory arose from the accumulated strength and proven fighting prowess of the Allied armies, their underlying materiel supremacy and the gradual collapse of German discipline in the face of inevitable defeat, exemplified by the arrival in strength of the American Expeditionary Force in the summer of 1918. The defining sequence of events had begun with the French defeat of a last gasp German offensive at the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918. It had continued with the stunning victory achieved by the British on 8 August at Amiens, which then premiered the Hundred Days advance to victory. It is the later stages of that decisive series of battles that concern us here. The Germans had fallen back in disarray, taking shelter in the comforting fastness of the Hindenburg Line. This had served them well in the past they had high hopes that it would serve them well again and were confident that they could prolong the war into 1919, if not beyond. Yet the Allied Supreme Commander, Marchal Ferdinand Foch, coordinated a sequence of offensives that cracked open the Hindenburg Line with the result that German resistance began to crumble. The Fifth Battle of Ypres, the Battles of the Sambre, the Selle and the Meuse-Argonne all victories for the Allies. Yet what do we remember of them? Scant details appear in general books on the war; indeed there is little of relevance in most works devoted solely to 1918. All that seems to matter is the death of the (then) relatively unknown poet Wilfred Owen during the crossing of the Sambre on 4 November 1918. This though sad should not be our focal point in considering these huge offensives. They were intended to smash through the German lines, allowing no time to rest, no chance to bring up reserves, no time for the German commanders to catch their breath and review the situation rationally. The German High Command was left helpless, scrambling to react to situations that were already in the past. Unable to second-guess where the Allies would strike next, and without the manpower or resources to be strong everywhere, they stumbled from disaster to disaster.

But it had not been easy.

For the Allies did not have a monopoly in courage. The German Army may have reached the end of its metaphorical rope in the summer of 1918, but, even after four years of carnage, there were still plenty of grim unbending soldiers willing to carry on fighting to the very end. Their spluttering machine guns and booming gun batteries took a heavy toll of the attacking Allies. Many German soldiers demonstrated an unbelievable resilience, contesting every yard of ground, despite the dawning realisation that their cause was hopeless. Their sacrificed lives bought time for their comrades to retreat, take up new defensive positions and continue the resistance. Heroism and tragedy were all around during the final days of that terrible war.

Next page